Learning From The Women At Home

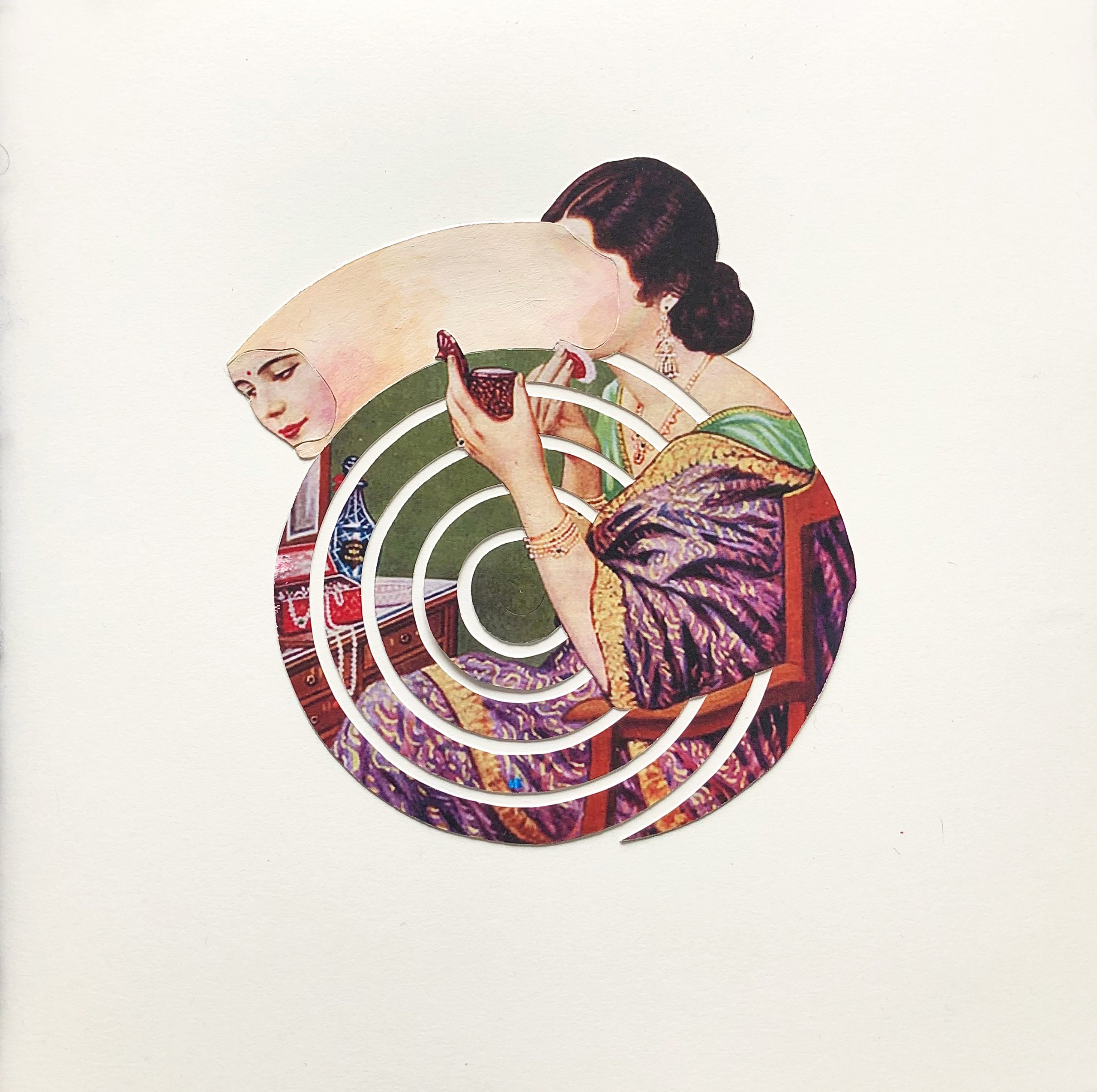

In early February of 2020, I was hired by Poster House as a part-time educator, and I was serendipitously introduced to yuefenpai—calendar advertisements from China—with the current exhibition The Sleeping Giant: Posters & The Chinese Economy. Seeing these elegant posters took me back to 2017, when I had started a series of collages using calendar posters from pre-independent India. My practice dissects oppressive South Asian traditions by using objects and visuals that propagate it. Needless to say, my relationship with the calendar posters from India is complicated.

Left : Friends=, Empire Calendar Manufacturing Company, ca. 1942

(image c/o Mani Karthik)

Right: W**** At T**, Maya Varadaraj, 2017

(image c/o the artist)

Learning about yufenpai and teaching with them made me notice details I had previously missed in the Indian advertisements—details such as the graphics on the products being sold or the slight change in fashion from decade to decade. I was energized to revisit my collage series and found a fresh batch of images to print and collage.

Then COVID-19 took New York City by storm. Being in quarantine and engaging with people through technological frames is giving me a new perspective on these women.

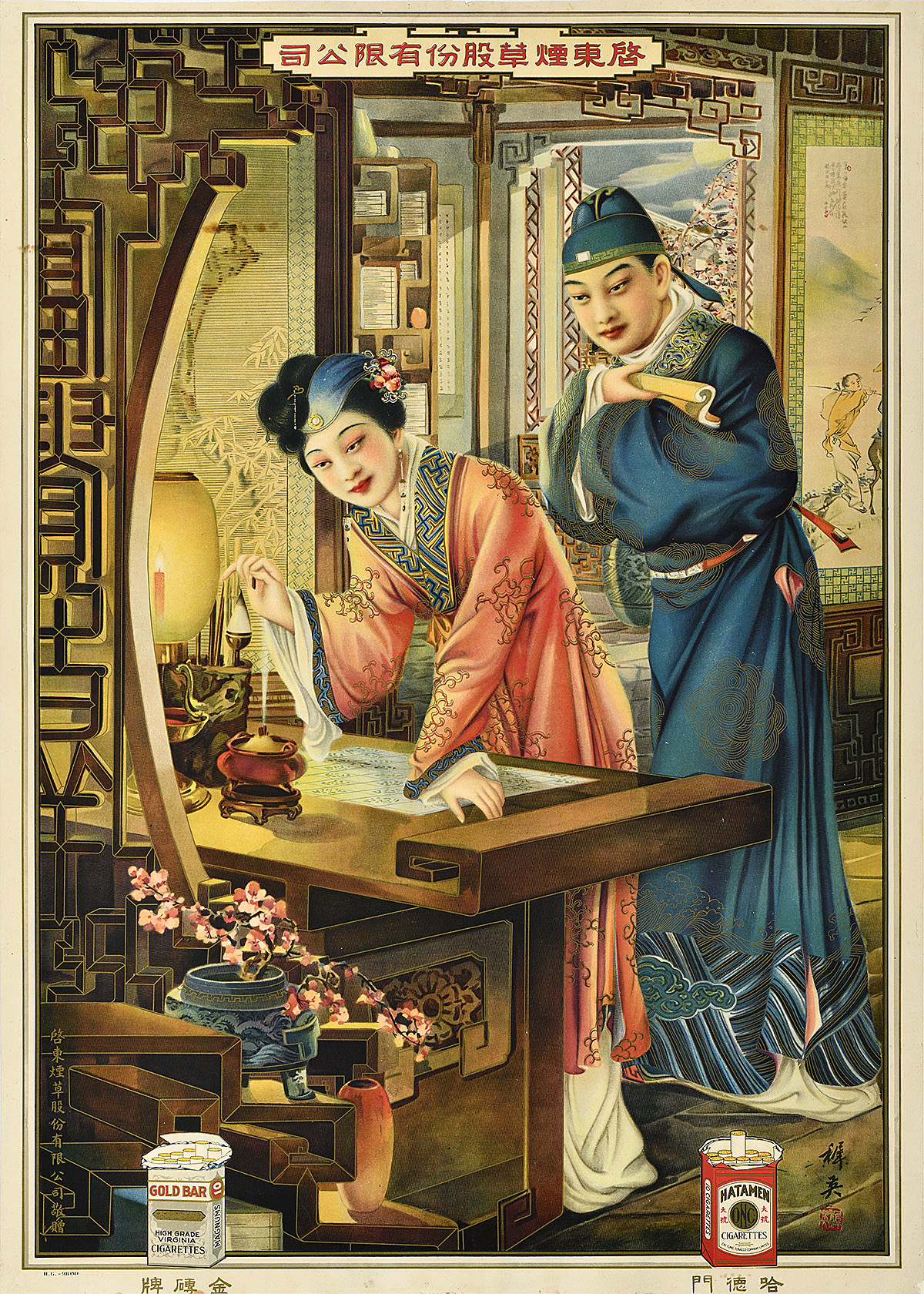

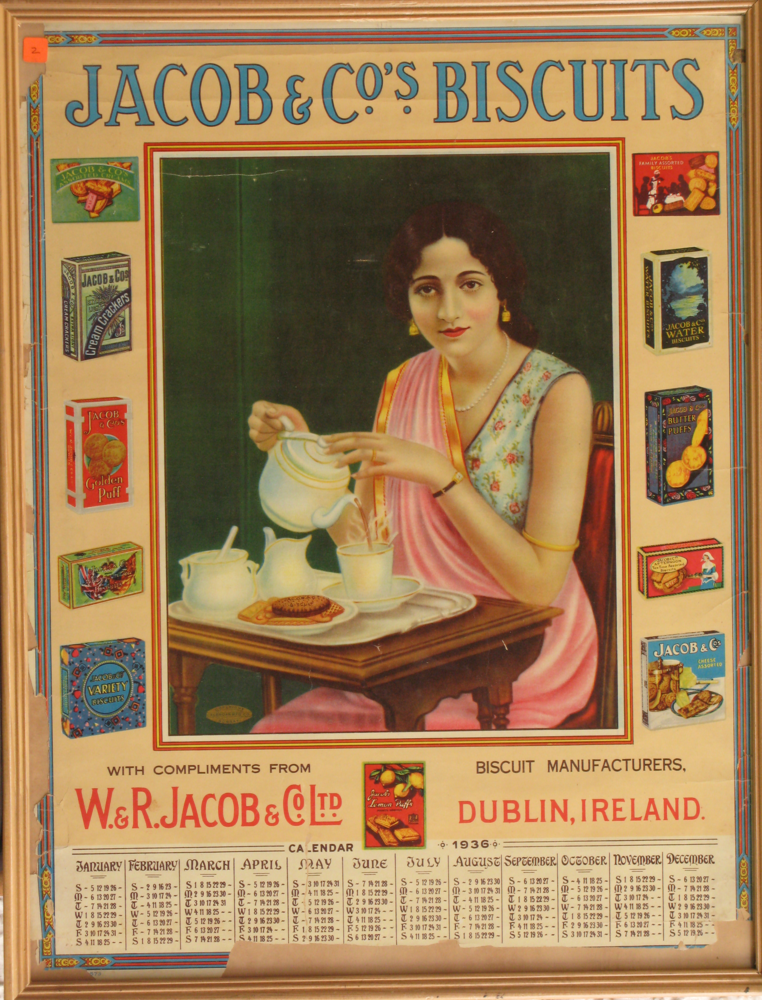

Left: Nestlé Condensed Milk, Zhiying Studio, 1931

Collection of Marc H. Chocko

Right: Jacob & Co’s Biscuits, Designer Unknown, 1936

(image c/o Universität Heidelberg)

In retrospect, it is easy for me to say that these images of women confined to domesticity, passivity, and the male gaze are restrictive. However, having been confined to my own apartment for the past three weeks, I’m finding escapes of hope and joy in objects and visuals that are in my home. As I sit in front of these new images to collage, I begin wondering whether these beautifully-framed women were also windows of hope, aspiration, and joy for the women who lived with them.

In order to understand these women better, I researched revolutions, policies, and laws related to women’s rights at the time of these posters. My findings show an interesting relationship between the political and social changes that these women were experiencing and the posters that eventually speak for them.

Yuefenpai 1900s—1949

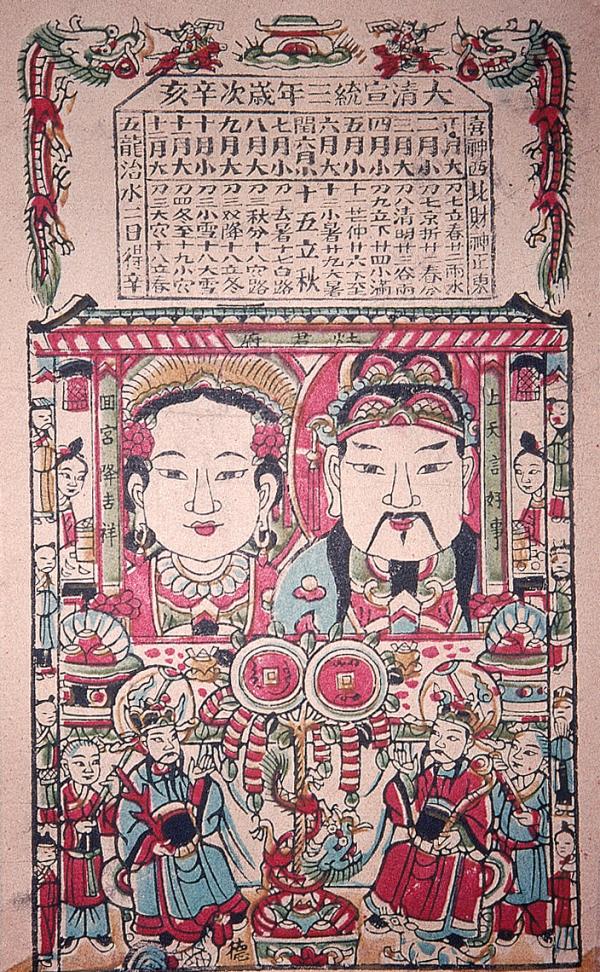

Yuefenpai (meaning “calendar advertisements”) from China were marketing products used by Western companies that had a strong influence on the Chinese economy after the Opium Wars in the 19th century. These images are a combination of Western promotional posters and traditional Chinese woodblock-printed calendars, also known as nianhua. The ubiquitous need for a calendar to check auspicious dates in the Chinese household quickly made the yuefenpai a popular product.

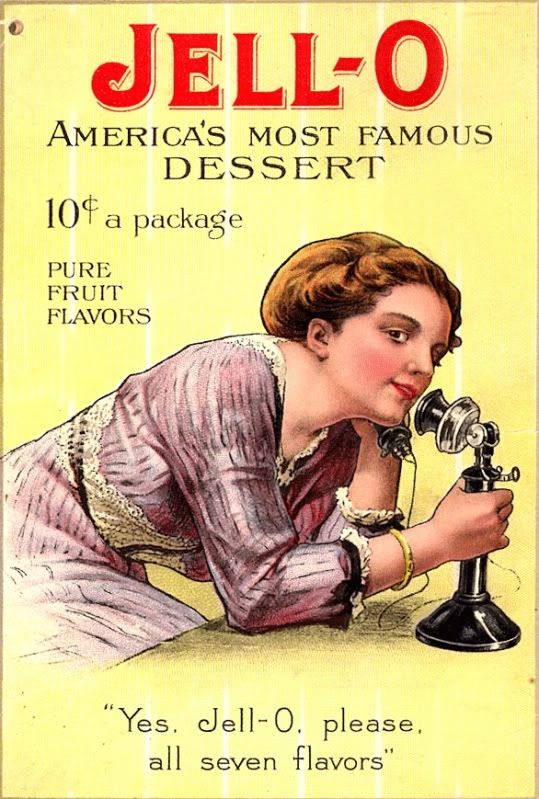

Left: Jell-O, Designer Unknown, 1901

(image c/o Pinterest)

Right: The Kitchen God and His Wife, Designer Unknown, 1910

(image c/o MCLC, Ohio State University)

Yuefenpai were used from the early 1900s until 1949, when they disappeared as the Communists took over Shanghai. In half a century, the status of women changed dramatically.

The most notable changes in the status of women were the result of the demise of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. The Qing Dynasty’s reign lasted from 1644—1911 in China. Like many preceding dynasties, the Qing Dynasty adopted Confucian ideologies that favored the patriarchy. Chinese women had little to no rights during this time. The traditions of foot binding, widow chastity and suicide, and forced marriages were prevalent. Women were not educated and were mostly confined to their homes unless their family required field help.

At the advent of the Opium Wars, there was increased trade along the Silk Road in the mid-19th century. Concern and dissatisfaction with the Qing’s inability to protect their economy from foreign forces grew within the population. Revolutionary groups and anti-Qing secret societies were forming. Among these revolutionaries was Qiu Jin, the most notable female revolutionary, feminist, and writer from this time.

Qiu Jin was a strong advocate for women and spoke openly about abolishing foot binding, forced marriages, and fought hard for women to be educated. She published a women’s journal and a newspaper, and was the head of a school that secretly offered military training for revolutionaries. Although she did not live to see the revolution, Qiu Jin paved the path for the empowerment of women in China. She was publicly beheaded in 1907 at the age of 31.

This is one of her poems:

Crimson Flooding into the River

Just a short stay at the Capital

But it is already the mid autumn festival

Chrysanthemums infect the landscape

Autumn is making its mark

The infernal isolation has become unbearable here

All eight years of it make me long for my home

It is the bitter guile of them forcing us women into femininity

We cannot win!

Despite our ability, men hold the highest rank

But while our hearts are pure, those of men are rank

My insides are afire in anger at such an outrage

How could vile men claim to know who I am?

Heroism is borne out of this kind of torment

To think that so putrid a society can provide no camaraderie

Brings me to tears!

Qiu Jin Translation by Michael A. Mikita, III

In 1911, the Qing Dynasty was overthrown and the Republic of China was established. Under the new government, Confucian ideologies that subjugated women were seen as backward, and many violent practices were abolished, including widow chastity and suicide, as well as foot binding. Modernization and progress were the main agenda and women were encouraged to be educated and join the workforce.

The tradition of foot binding was among the most painful in women’s history within China. Efforts to end this practice started in the mid-19th century. Interestingly, Christian missionaries who educated girls played a major role in convincing the upper class to end this tradition in their families. In 1912, the tradition was finally banned, but it was not until 1929 that there were no new cases of foot binding in China.

In this light, perhaps the elegant ladies of the yuefenpai were role models that upheld and encouraged the new ideologies of Modern China. They wear their traditions with pride while embracing new opportunities to reflect progress ever so gracefully.

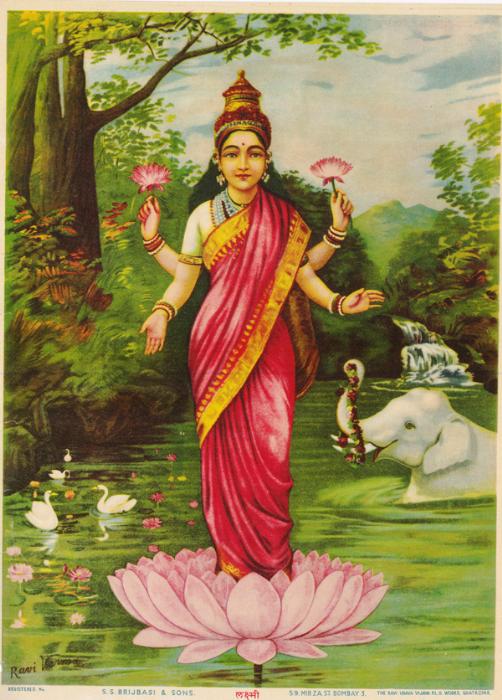

Left: Lakshmi, Ravi Varma, c. 1906

(image c/o Culture Trip)

Right: Sunlight Soap, Ravi Varma, c. 1933

(image c/o Rami Vara Facebook Page)

Calendar Advertising Posters from Pre-Independent India, 1890s—1947

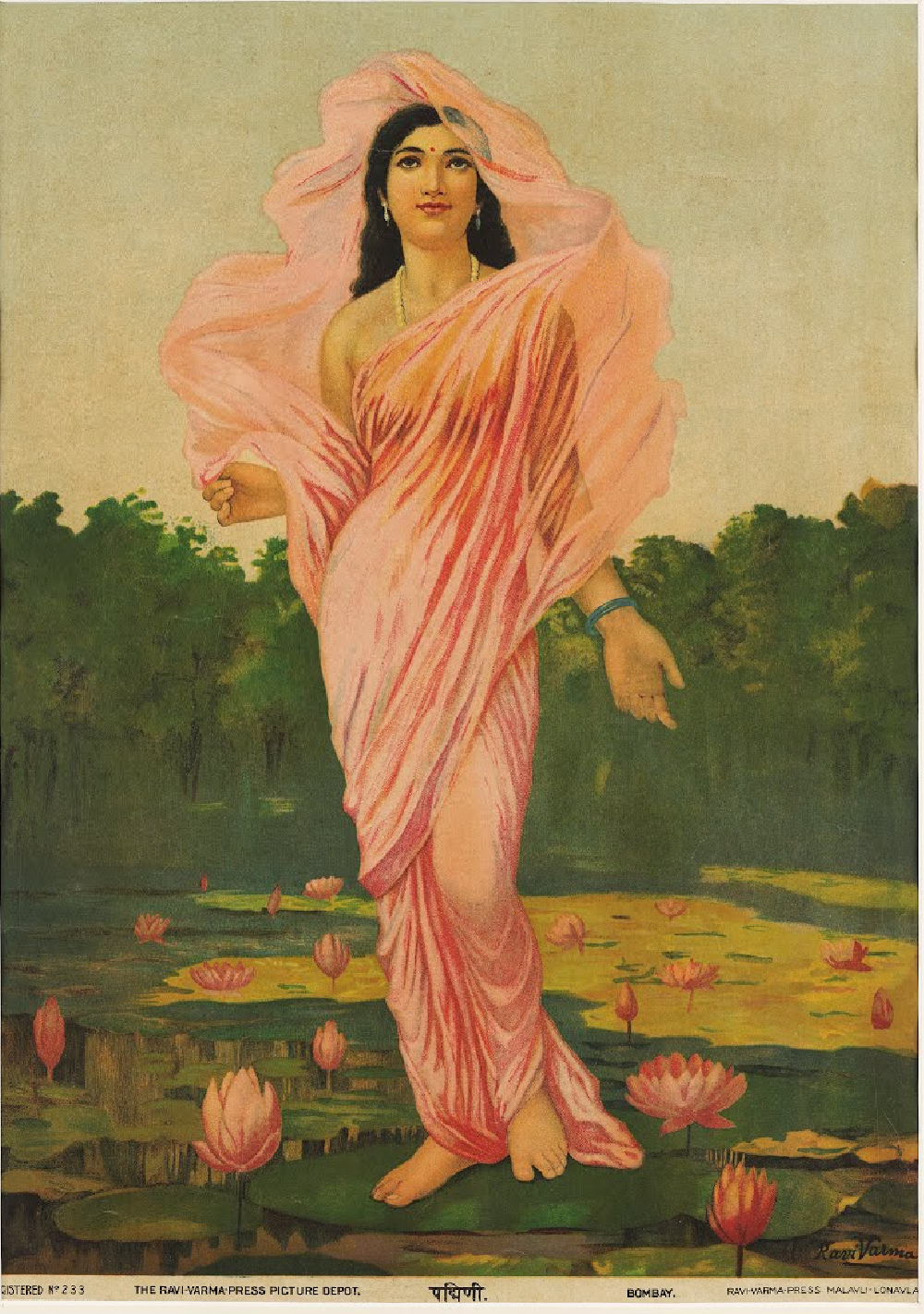

Like yuefenpai in China, Indian calendar advertisements also had a pre-existing niche to be welcomed with open arms into the Indian home. While there is a habit of using calendars for auspicious dates and festivals, the need for images of deities for the home altar paved the way for calendar advertisements in India. At the forefront of these auspicious images is the artist Raja Ravi Varma.

Raja Ravi Varma is the most famous classical painter in India. His style of painting referenced Western classical painting while using Indian subjects, and garnered a massive global following. In 1894, Ravi Varma set up a lithographic press named after himself, it was the largest and most popular press at that time. The images made available through this press changed the accessibility, approach, and ownership of art and visuals in India.

Soon, households across classes in India sported Ravi Varma prints. In 1901, when Fritz Schleicher, the printing technician, took over the press, he broadened the printing to include commercial advertising labels. This is another similarity to yuefenpai, as the central images of both yuefenpai and the Indian advertising posters are stock images used with various products.

Left: Mahaluxmi Soap Works, M.L. Sharma, 1935

(image c/o Mani Karthik)

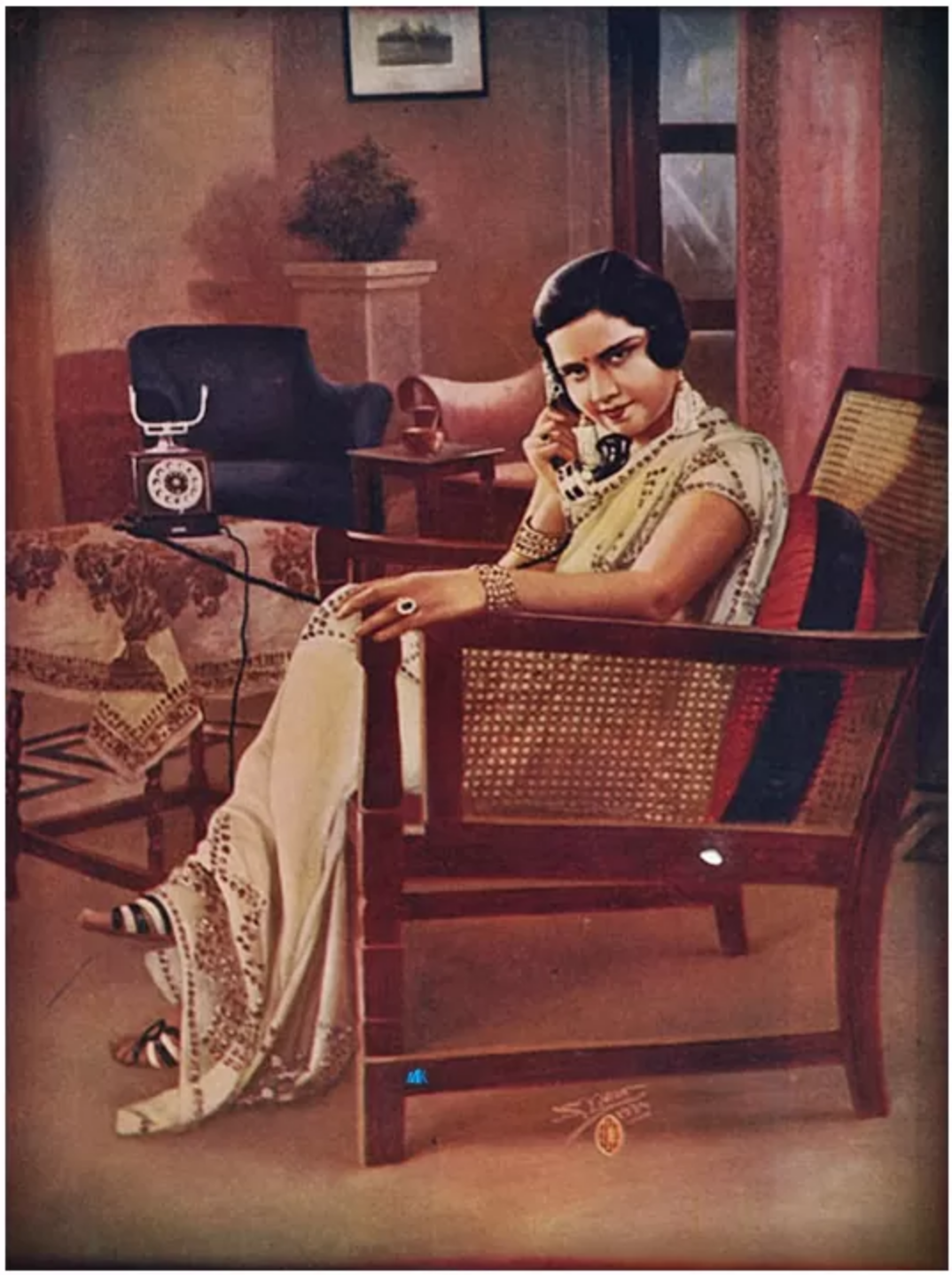

Right: Woman on Telephone, S.L. Jain, 1934

(image c/o Mani Karthik)

In addition to Ravi Varma’s images, other (mostly anonymous) artists were employed by large advertising firms to produce images of women, children, and families to advertise Western products. These images were not religious and therefore reflected colonial influences on fashion, decor, and lifestyle at this time.

Ravi Varma’s subject matter, although religious in nature, was predominantly women, which is an interesting correlation to the advertising posters that were not his work. Were the ordinary women somehow elevated because they were presented in the same form as the Ravi Varma deities? Or were they demoted for the same reason? The differences between these two women will evolve to encompass the growing tension between nationalists and the British Raj.

Left: Rambha, Ravi Varma Press, c. 1925

(image c/o Citravali)

Right: Padmini, Ravi Varma Press, c. 1930

(image c/o Google Arts & Culture)

Women’s history in India is particularly confusing, as the level of freedom and visibility varies by region, religious affiliation, and class. Nonetheless, the general status of women in India at this time, much like their Chinese neighbors, was low. They were also subject to oppressive traditions such as female infanticide, forced child marriages, dowry enforcement, widow immolation, and mistreatment. The first phase of empowerment in the mid 1800s to 1915 was actually initiated by the British to bring more colonial ideals to the population. The ban on the practice of Sati, whereby a widow must be burned or buried alive with her deceased husband, was passed in 1829 but did not include princely states until the 1850s. Efforts were made to educate women as schools were set up specifically for them; however, these efforts were interrupted with the nationalist uprising that wanted to guard traditional Indian—more specifically Hindu—identities of gender and family structure from colonial influences.

The second wave of feminism from 1915 to 1947, was more strategic in that it aimed to create a strong identity for Indian women that rivaled the Victorian counterpart. Mahatma Gandhi encouraged the virtues of a woman as a care-giver and praised qualities of tolerance, patience, and self-sacrifice. Nationalist sentiments were stronger and women, under the guidance of Gandhi, participated in the non-violent civil disobedience rebellion against the British.

Here is where we revisit the two distinct ladies of advertising posters from pre-independent India. By this time, Ravi Varma’s popular paintings had become nationalist symbols along with work from other artists such as Rabindranath Tagore and Jamini Roy. The posters of his work became subtle nationalist propaganda, whilst the ladies sporting the fusion of colonial and traditional styles became anti-heroes that bore similarities to their Victorian friends. The fact that they usually advertised Western products or were created by Western advertising firms furthered their anti-patriarchal character.

The traditional deities in the prints aroused nationalist sentiments and encouraged women to uphold their traditions that included being inferior to their husbands, while their counterparts promised progression and autonomy. These disconnected realities were reflective of the confused state of affairs for Indian women at this time and marks another instance in history where women were used to play political tug-of-war.

Left: Woman Powdering Her Chin, Designer Unknown, c. 1942

(image c/o Mani Karthik)

Right: It Was All Touch And Go For A While, Maya Jay Varadaraj, 2020

(image c/o the artist)

In 1947, India gained independence and Pakistan was established; their women were once again forgotten as the two countries faced major economic and political turbulence.

I’m sitting in front of my collages, and I feel a sense of gratitude towards these women who have in their own small way contributed to my privilege of being able to work with them. Being confined to my home has allowed me introspection and revision. It has also changed the way I connect and share with my friends and family. My intentions seem to be more clear and meaningful since everyone is in a frame of sorts. On that note, I’d like to ask if there are images and objects in your own home or ones that you’ve encountered digitally in quarantine that have changed your mind about something?

Maya Jay Varadaraj is a teaching artist at Poster House. She can be reached through her website or on her Instagram account (@maya_vara), and would love to know where you are finding similar inspiration during this time of quarantine.