The Sleeping Giant: Background to the Tour I Have Yet to Give

Tim Medland is a docent at Poster House. Hailing originally from the UK, he is pursuing an MA in museum studies after a career in the financial world. He loves giving tours in English or French and sharing his passion for material culture and the arts in general. When we reopen, he will be lobbying hard for the museum to adopt a small, white museum dog to be named after Tintin’s canine sidekick, Snowy, or Milou in French.

The Sleeping Giant is our largest exhibition at this moment in time. In the first ten days after the exhibition opened, I led a few tours from a one-on-one tour to a large tour to a group of Quebecois graphic art university students. Then the Covid-19 hiatus happened, and management bravely took the decision to be the first museum in Manhattan to close due to the virus.

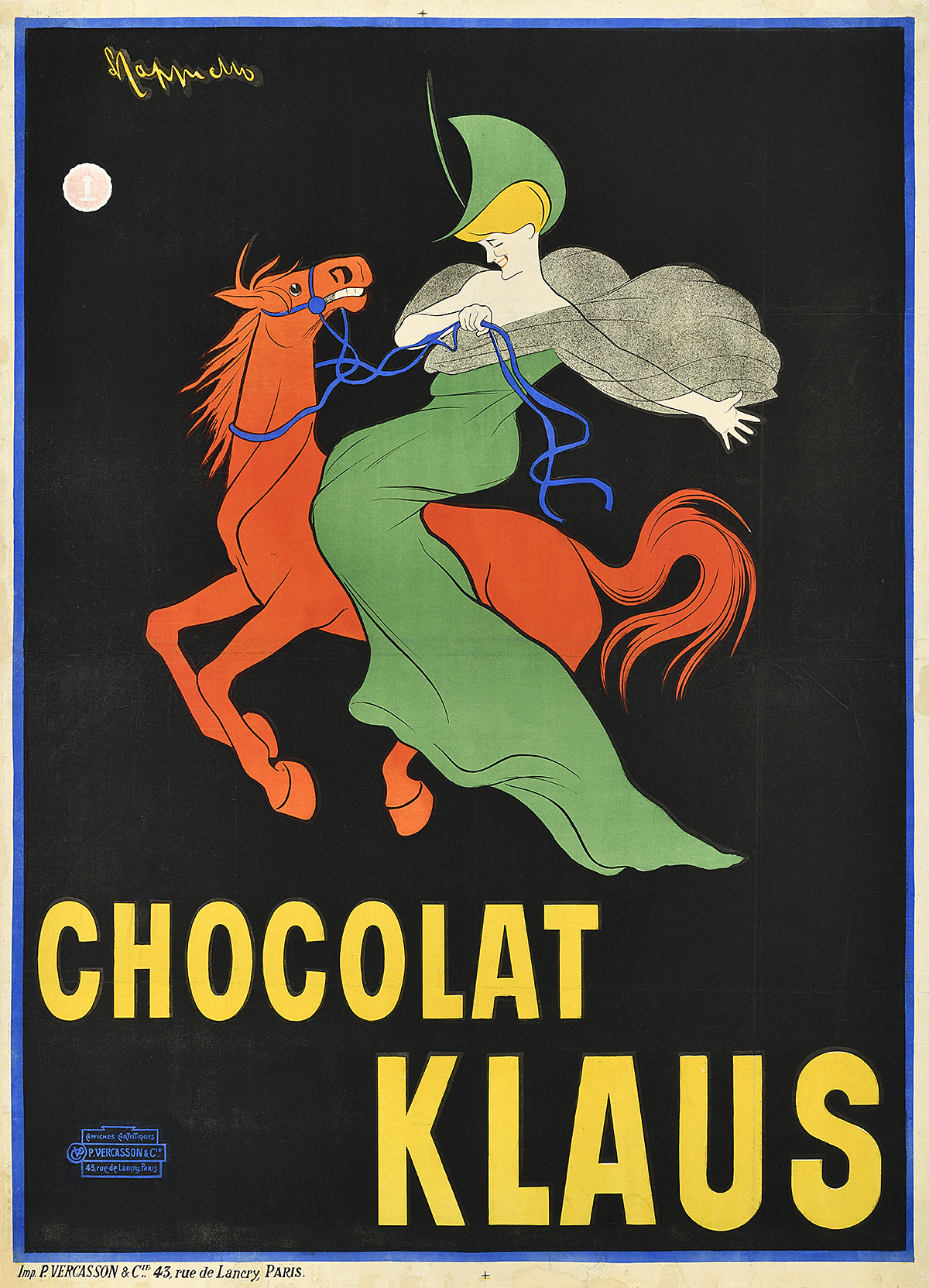

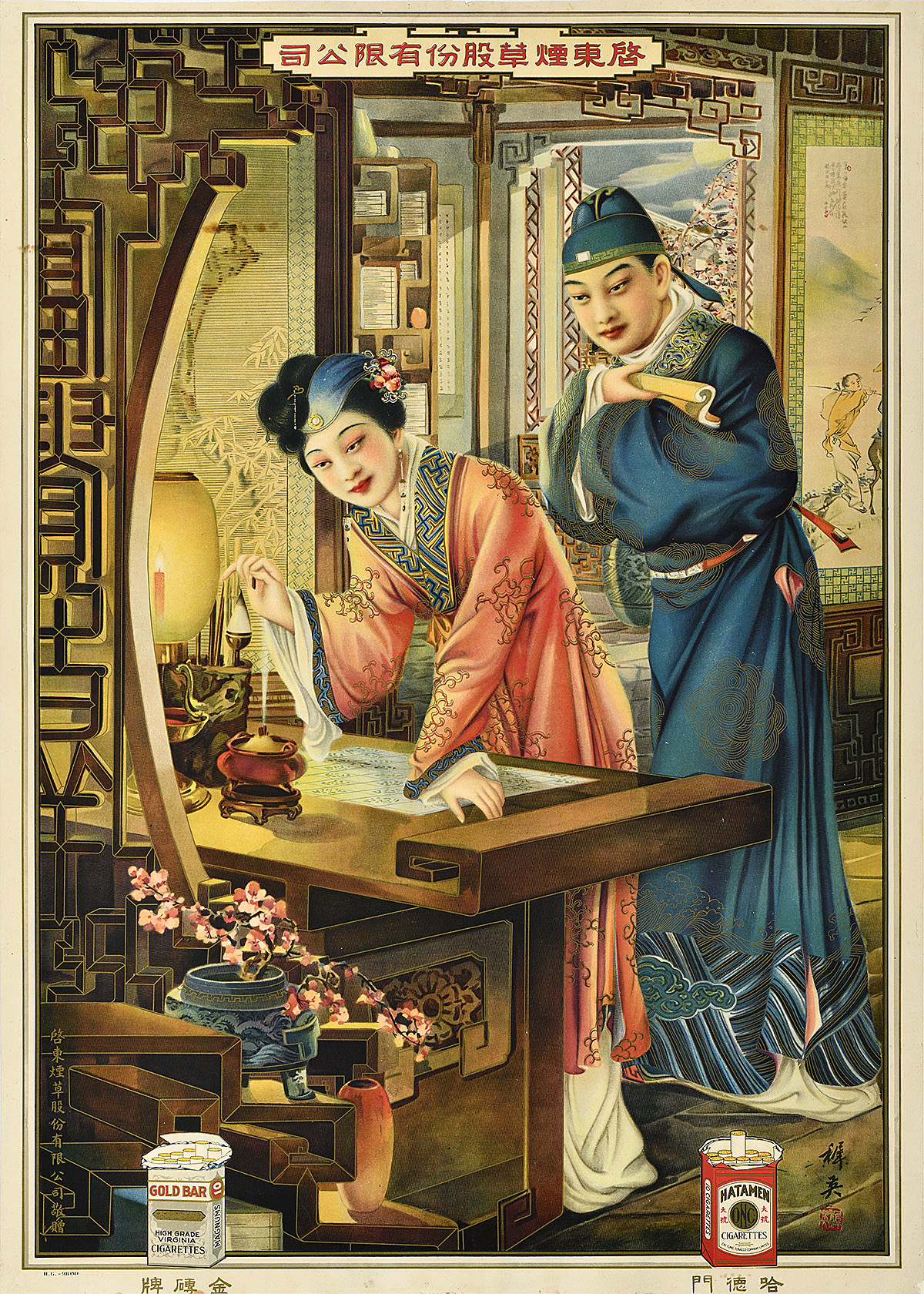

Qidong Tobacco Co./Gold Bar and Hataman Cigarettes, Zhiying Studio, c. 1928

From the Collection of Marc Choko

Why am I a volunteer at Poster House?

Firstly, a little personal background. With my thirty-year career in finance over, I am cementing my status as a museum nerd by undertaking a Master’s degree in Museum Studies while volunteering. So, why at Poster House? Besides the obvious fact that I am interested in posters, there were three key issues that attracted me to volunteering at this particular museum.

For one, it is a small start-up. While all institutions carry baggage and skewed incentives, issues increase exponentially with history and size. Museums are cumbersome structures that, almost by definition, are biased towards tradition. Here we start with the proverbial clean sheet, and I can hopefully be of use in multiple ways in a museum which can focus on different issues than larger museums.

Secondly, the management team is primarily female.

Lastly, and crucially for me, I appreciated that at Poster House docents would learn about each exhibition from the curators, but we have freedom in our interpretation of it. Each guided tour contains the same core facts but involve a great deal of personalization.

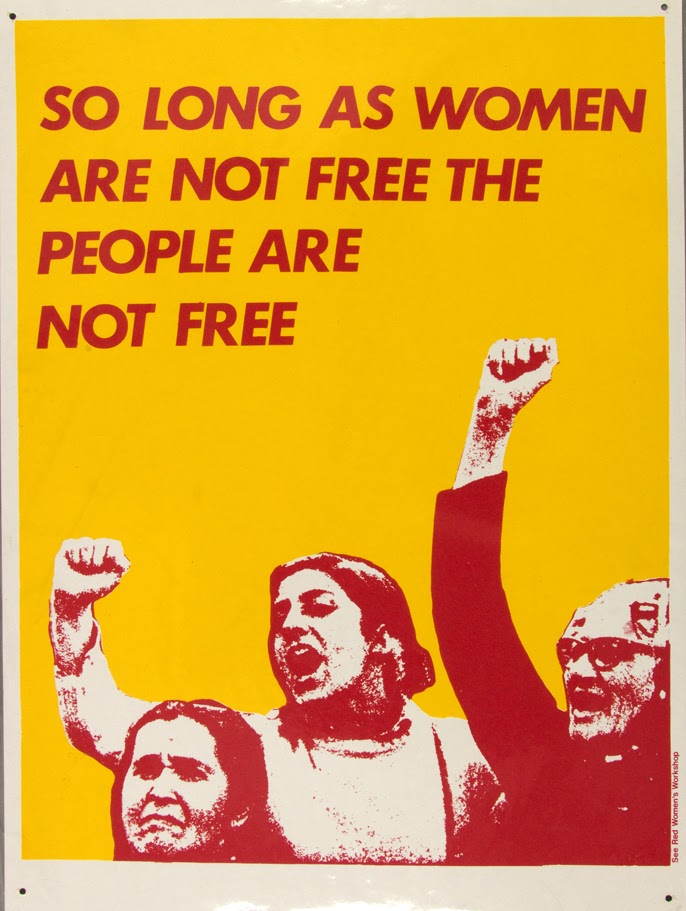

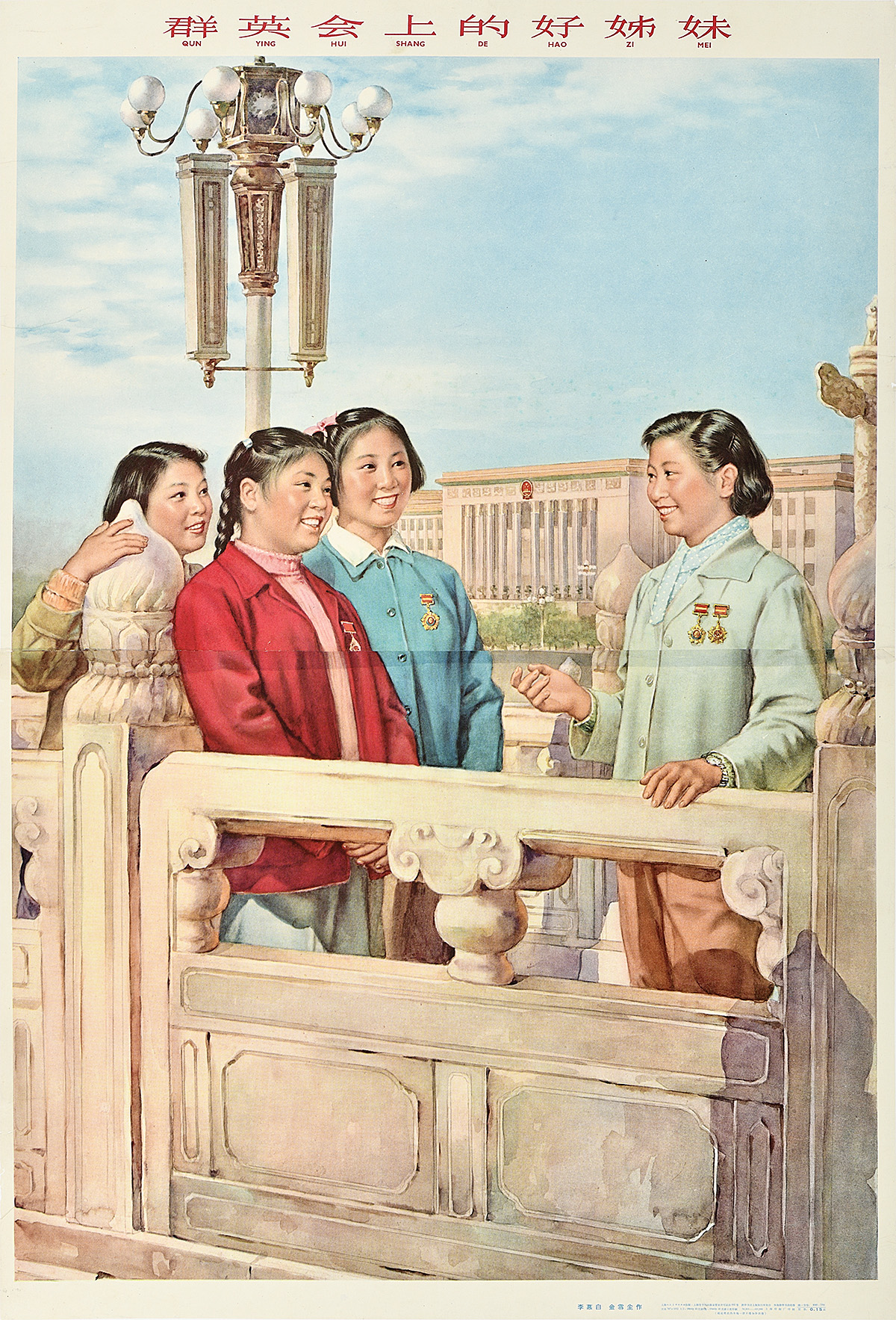

“Sisters” Meeting of all Regions for the National Heroes Conference, Li Mubai & Jin Xuechen, 1964

From the Collection of Marc Choko

What have I learned from guiding?

Thus far, I have found that guiding is an iterative process. The tour you give as the exhibition opens is not the one you give as the exhibition closes. You get asked different questions, conduct different research, and circumstances change during the time the exhibit is open (or in this case, sadly not). The tour at the end of the run may be more slick or edited than the one at the beginning, but that does not make coming early any less rewarding. To me, the museum does not have a monopoly on knowledge, and so the more interactive tours are often the most engaging. One of the primary purposes of the objects in an exhibition is to initiate a conversation, to leave space for thinking about them afterwards.

This exhibition should have been a natural for me given my background and the fact that I have visited China many times. Standard procedure is that the curator guides both staff and volunteers before the exhibition opens to the public and notes from the education department are distributed. Post that and before giving tours, I spend a few hours wandering around the exhibition, working out which posters appeal to me and why. That segues into my trying to fill in gaps in my knowledge via research, which as a nerd is my favorite part. This frequently leads to a book recommendation linked to the exhibition, if visitors are interested. I do not have a sample size of visitors large enough to verify this yet, but what strikes me is that many museum visitors are interested in art as history, rather than the history of art, and individual narratives added help enormously.

Brunner Mond & Co. Ammonium Sulphate, Zhou Baisheng, c. 1930

From the Collection of Oded Boldo

The Sleeping Giant-How do you deal with a problem like Mao?

In these first tours, I segmented the exhibit into four eras: Colonialism, war, Communism, and, lastly, what is now officially described as a “socialist market economy.” At the time we shut, I had not finished the first relevant book I intended to read, Wild Swans by Jung Chang, first published in 1991. The book describes the lives of a family; the narrator, her mother, and grandmother in the years 1910 to 1990, covering the same historical period as the exhibit. Whether or not you can come to see the exhibition, it is a phenomenal book.

The first part of the exhibition, the colonial period, uses elegant, glamorous women to advertise products in a Western/Chinese hybrid style. Many of these are incongruous given what is being advertised, my personal favorite being a fertilizer poster (see above). As you can see, the fur-trimmed lady will not be spreading a chemical mix on a ploughed field anytime soon, but the peasants in the margin are clearly grateful. The next part, war, when the country was resisting the Japanese occupying forces, is of necessity stark and violent. To me, the most intriguing part of the exhibit, and the one in which I had not really worked out what I wanted to say, is the Communist Maoist period. The rest of the exhibition is understandable to us as product marketing or war propaganda.

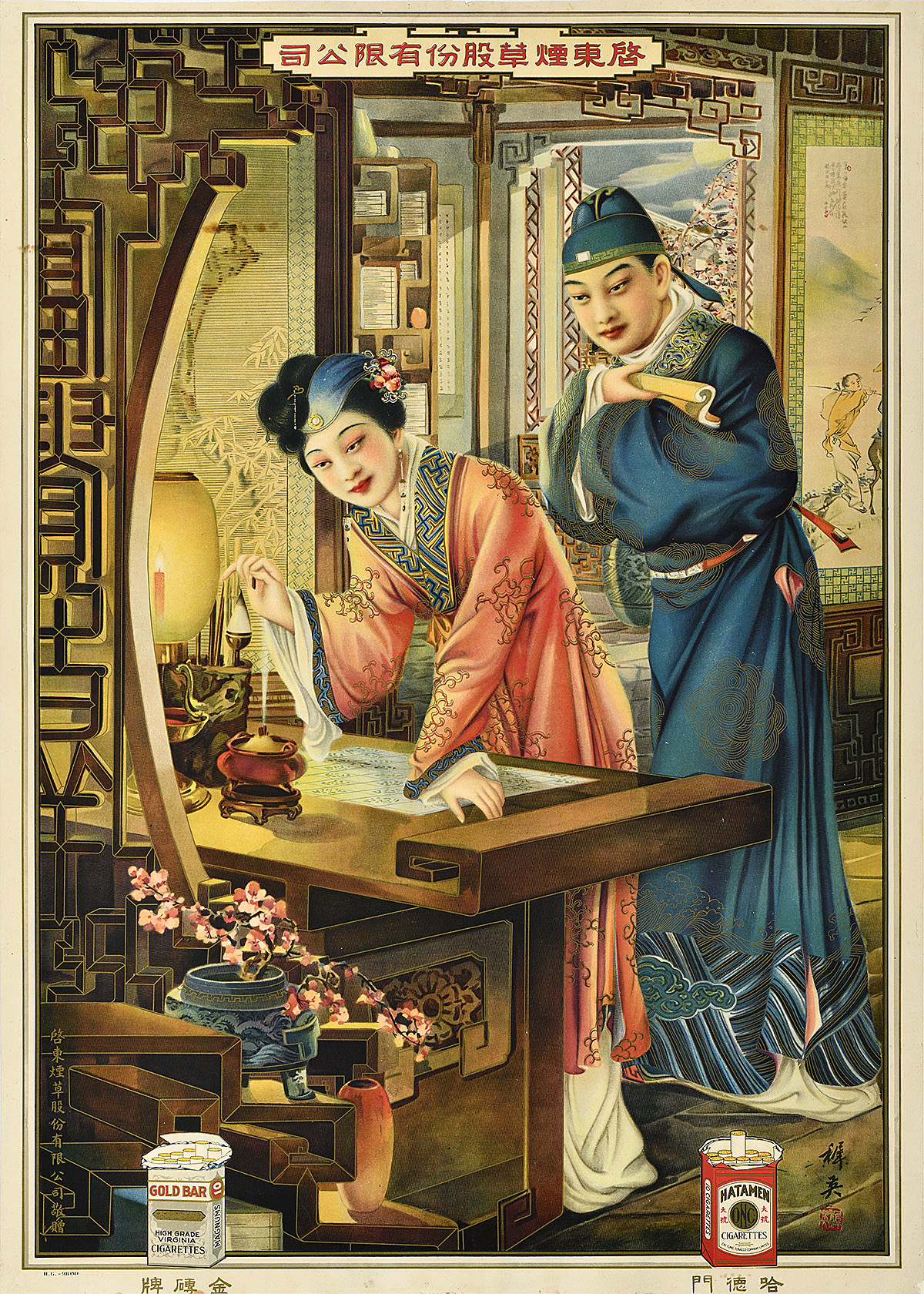

Carry Out People’s War Against Lin Biao and Confucius, Zhang Ruji & Wang Jiao, 1974

From the Collection of Marc Choko

Idolatry is a completely different issue. Jung Chang describes Mao in this way: “He was, it seemed to me, really a restless fight promoter by nature, and good at it. He understood ugly human instincts such as envy and resentment, and knew how to mobilize them to his ends. He ruled by getting people to hate each other. Because of his calculation that the cultured class were an easy target, because of his own deep resentment of formal education and the educated, because of his megalomania, which led to his scorn of the great figures of Chinese culture, and because of his scorn of the areas of Chinese culture that he did not understand, such as architecture, art and music, Mao destroyed much of his country’s cultural heritage.”

Mao is actually only in two posters and a vinyl wall piece in the exhibition, but his beliefs and actions are omnipresent in the other posters from the period where their kitschiness belie the harshness or violence of their message (see above). The philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote of the banality of evil, but reading the book, one is struck more by the ineptitude of the narcissistic despot, allowing his ill-considered beliefs to overwhelm science and competence. We wonder how rational people can fall for the deification of such a flawed individual. This was where Wild Swans helped so much, explaining how he eliminated or sidelined dissent, while his cult of the personality overwhelmed all other narratives, leaving the population to believe in him as the only person who could save them even as he made their lives immeasurably worse. Whether it be Mao’s curious dislike of sparrows and consequent wish to exterminate them, his insistence on cottage industry steel manufacture which turned good farmers into bad smelters, starving the country in the process, or the complete and utter evil and chaos of the Cultural Revolution, his real legacy is only pain.

One may not agree with the political system that prevails in modern-day China, but no one can argue that as soon as Mao was gone and replaced by Deng Xiaoping, China’s ascent started.

Love Tim as much as we do? Be sure to check out our weekly docent-led tours once we re-open!