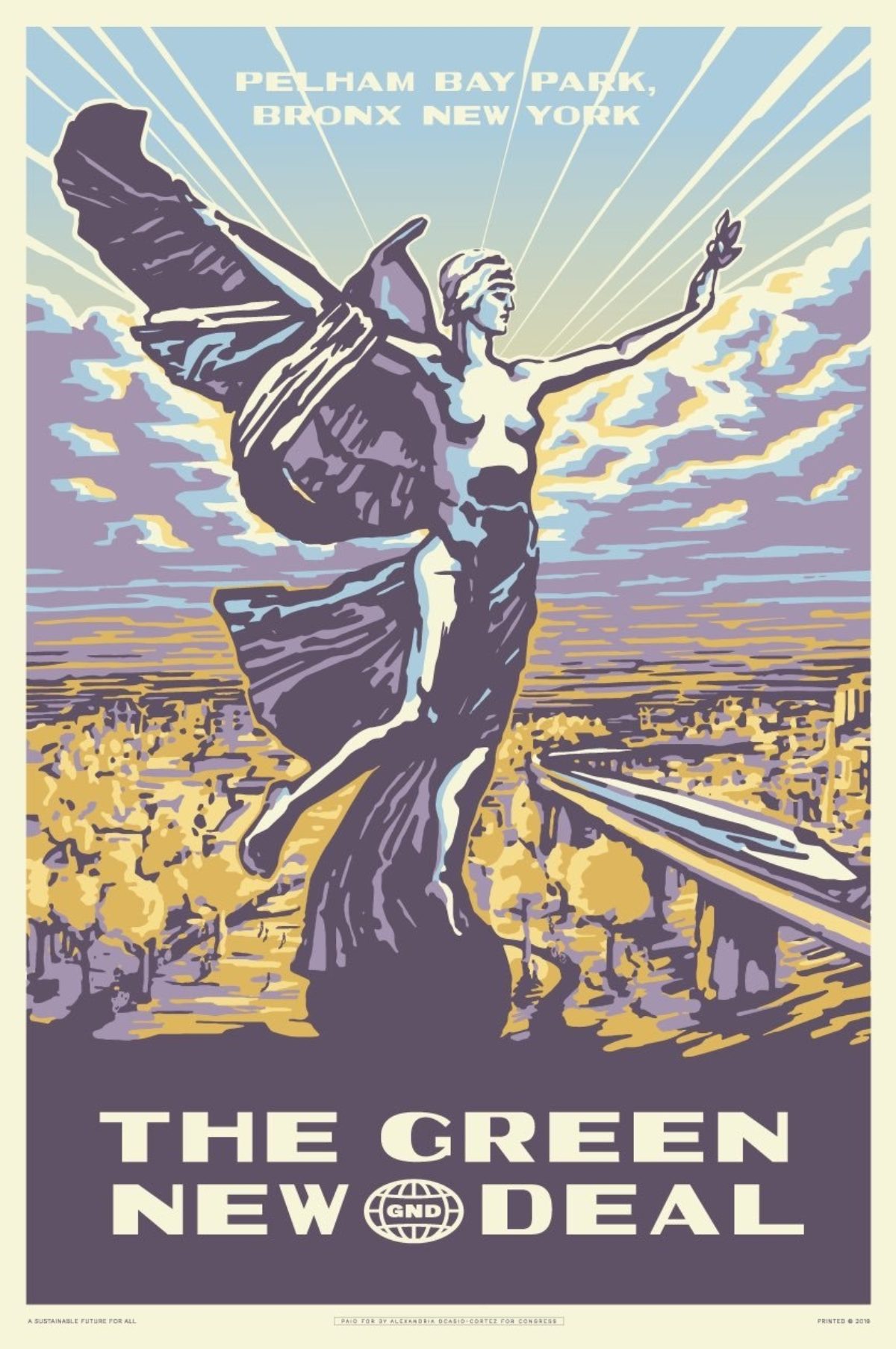

Mucha & Modern Advertising

This article by our Chief Curator is reproduced in its entirety from the Muse by Clio, where it first appeared on October 3, 2019.

Alphonse Mucha is a name that is synonymous with Art Nouveau, a sumptuous design movement from the turn of the 19th century that emphasized a return to nature in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. More than just a follower of this elaborate style, though, Mucha needs to be viewed as a pioneer in the history of advertising, having mastered—and in many cases introduced—concepts and techniques still used today.

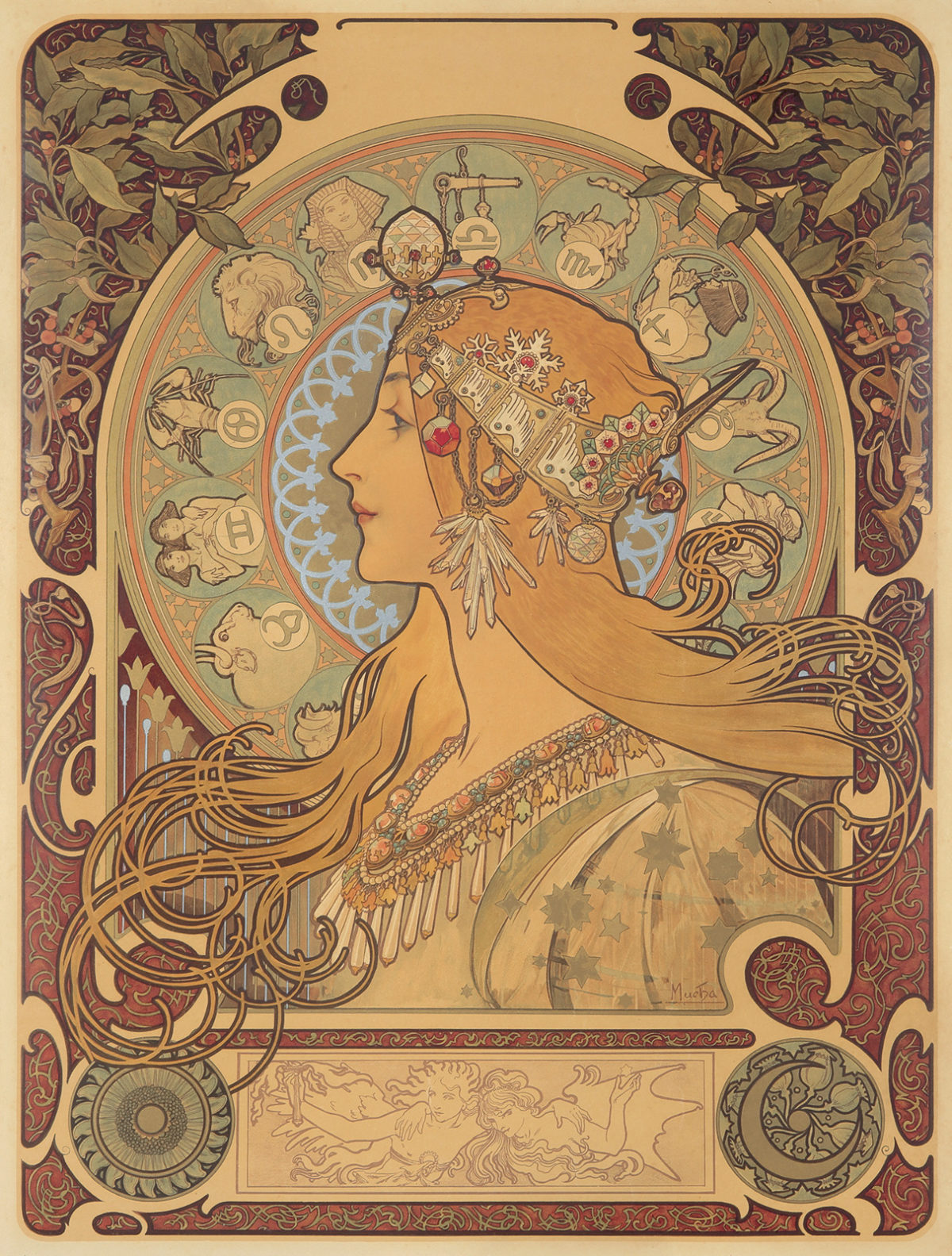

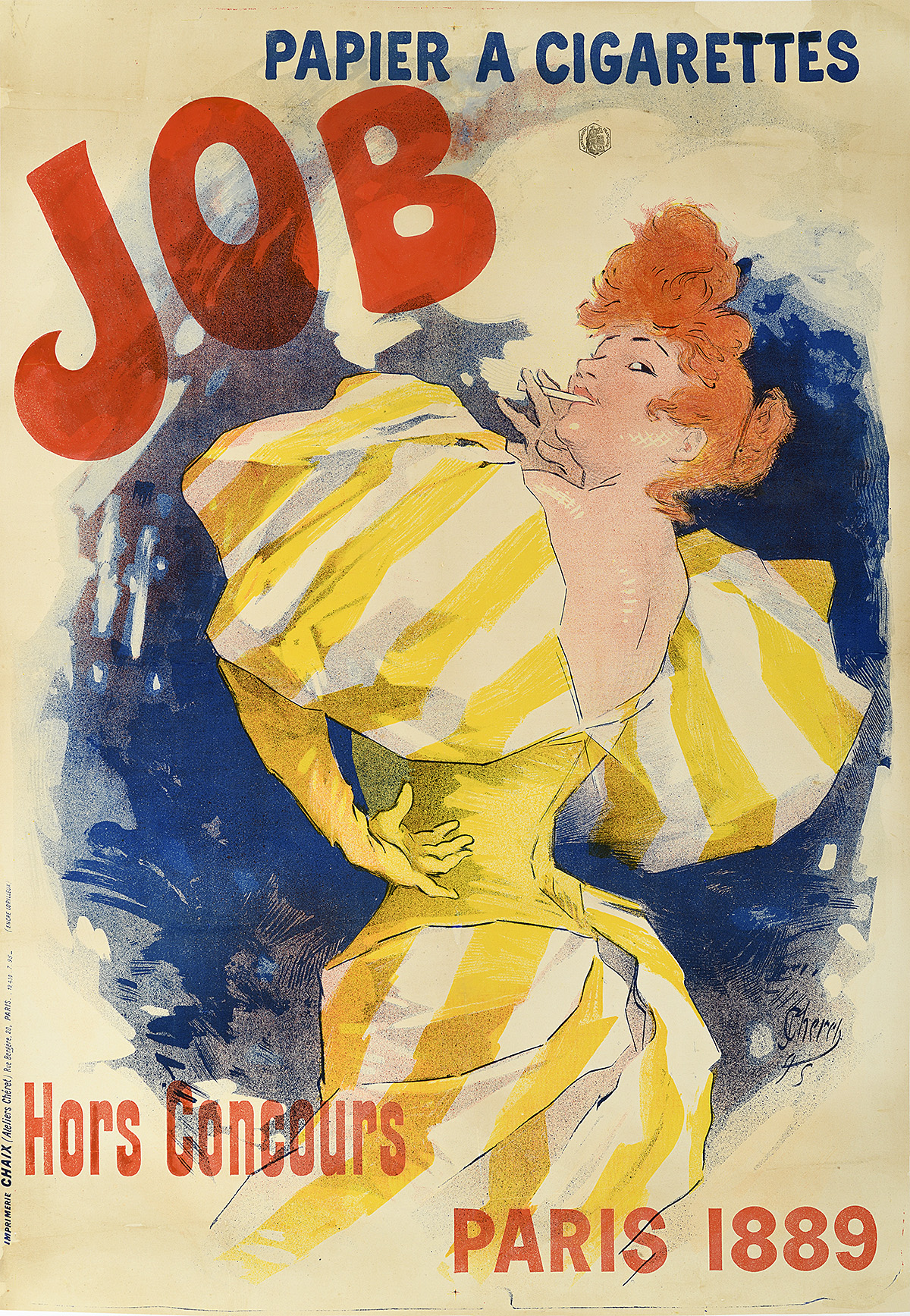

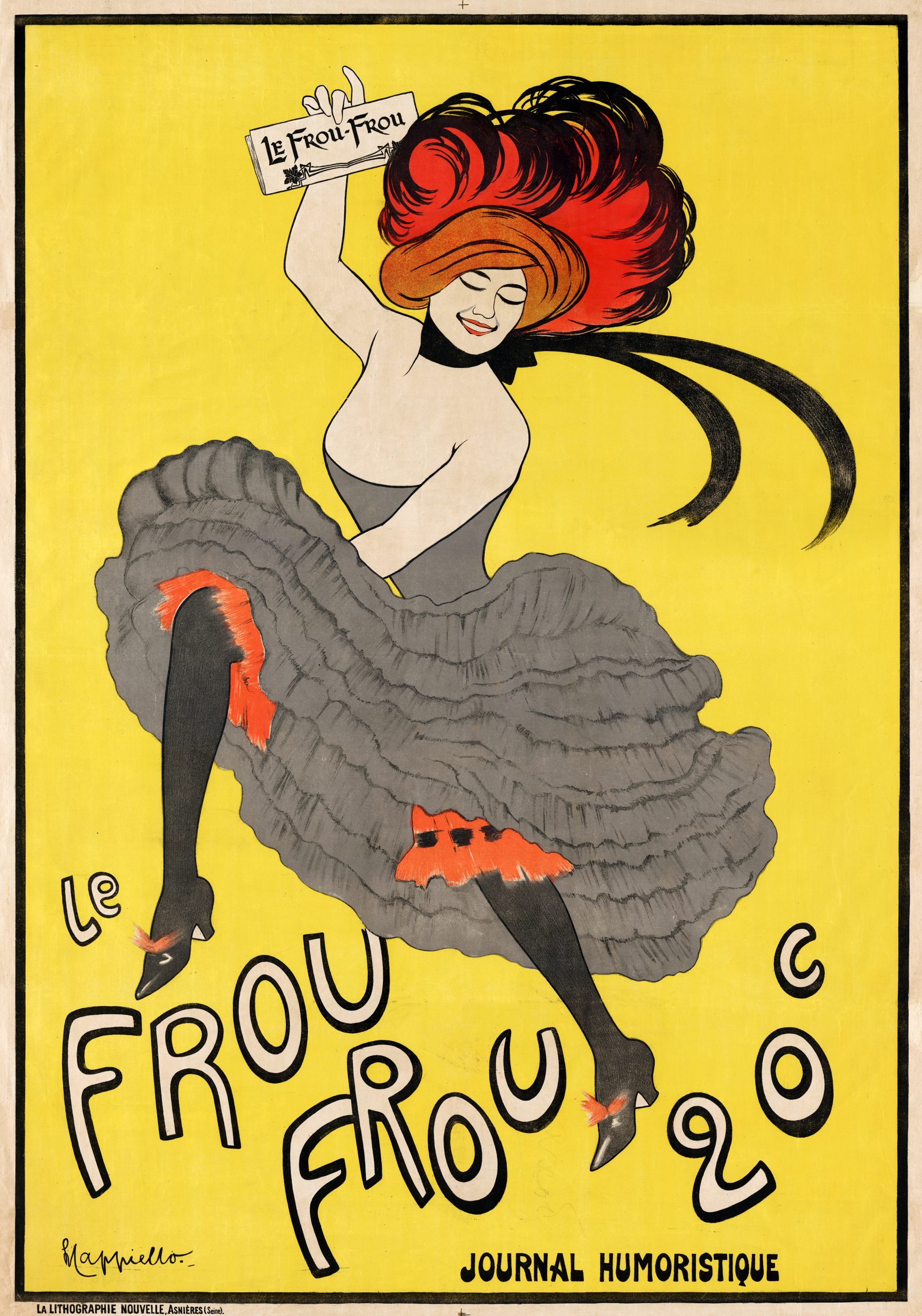

Mucha’s posters are revered for their incredible detail compared to those of his contemporaries. Like Jules Chéret and Leonetto Cappiello, Mucha came to poster design with an illustration background. Those artists typically celebrated the best parts of that craft in their designs, resulting in loose, caricature-inspired drawings that were more about whimsy and expression than realism.

Left: Job, Jules Chéret (1895)

Poster House Permanent Collection

Right: Le Frou Frou, Leonetto Cappiello (1899)

Image c/o Wikipedia

Mucha, however, wanted to maintain a level of high detail in his posters, and looked to new methods to find a means to that end. The answer was to work from photography, a technology with a relatively low barrier of entry thanks to the invention of celluloid film in 1887 and the introduction of commercially available equipment for amateurs—like the Kodak box camera—in 1888.

By the 1890s, Mucha was photographing models in his studio on a daily basis, amassing an archive of images from which he based almost all of his lithographic work. He became the first poster artist to work directly from photography, an influence that would go on to become standard practice by the 1950s in commercial design.

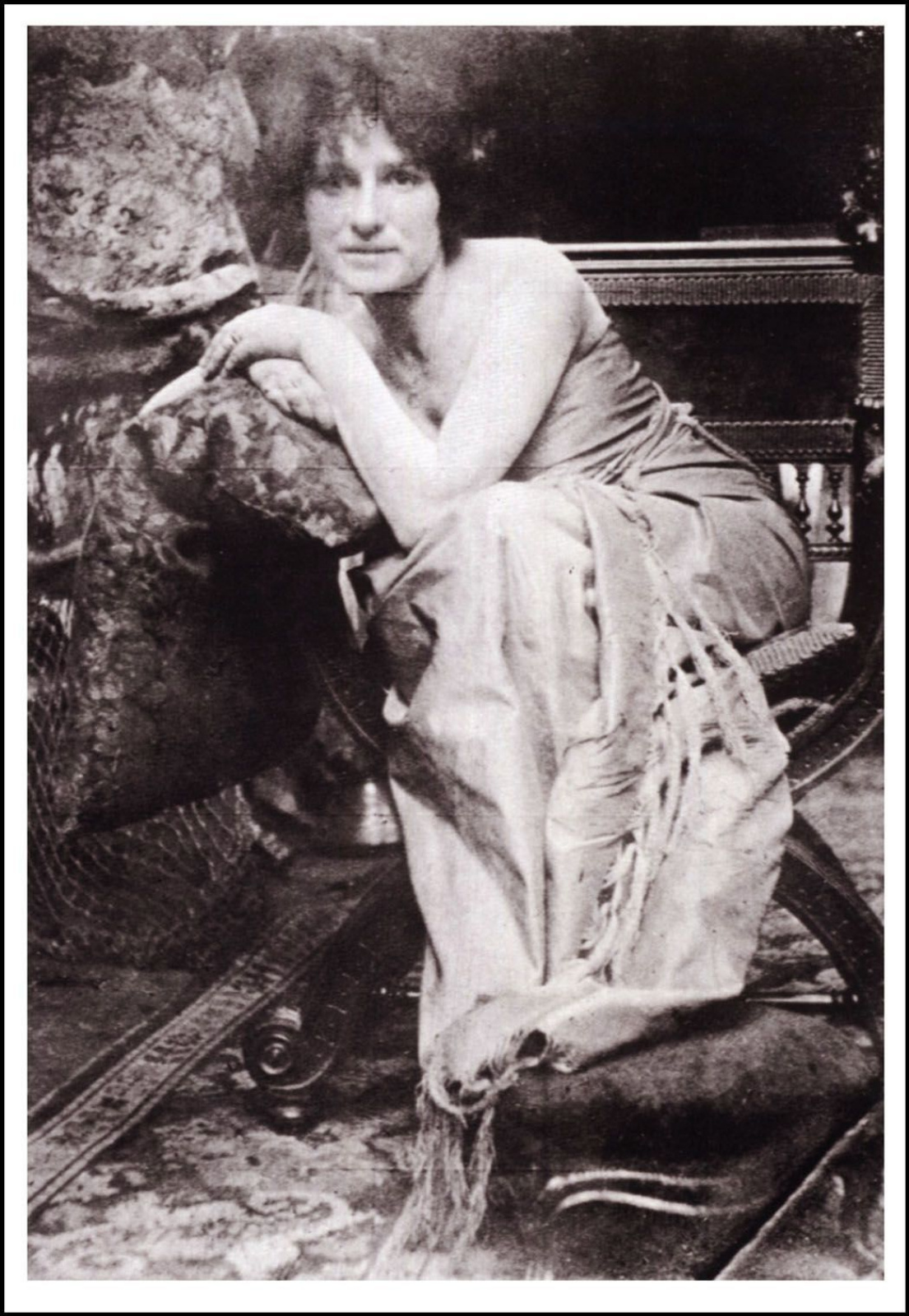

Left: Model in Mucha’s Studio (date unknown)

Image c/o The Mucha Foundation

Right: Emerald, Alphonse Mucha (1900)

Image c/o The Richard Fuxa Foundation

One also can’t talk about modern advertising without discussing the power of the celebrity endorsement. Nike, “Got Milk?”, PETA—some of the most memorable branding moments of our lifetime were thrust into the public sphere via famous faces. What did that look like 130 years ago? Well, many advertisers referenced recognizable figures to draw attention to their products, but without any real link between the celebrity and the object.

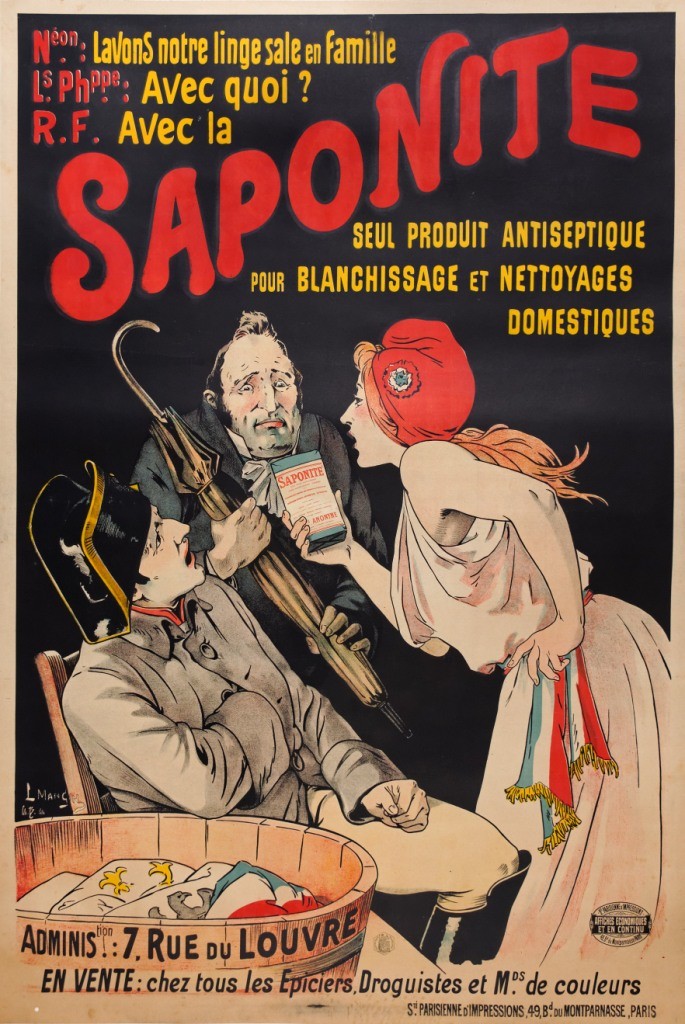

Take, for example, the 1894 poster below, for Saponite laundry detergent. Napoleon Bonaparte, King Louis Philippe, and the mythical figure of Marianne are gathered round, presenting the merits of this particular soap. But Napoleon had been dead since 1821, and Louis Philippe since 1850. Neither would have ever have had contact with or knowledge of this brand.

Saponite, L. Mangin, (ca. 1894)

Image c/o Original Poster Barcelona

Mucha, however, gained his own celebrity status through his posters for the unparalleled Sarah Bernhardt, the Beyoncé of her day. A PR juggernaut, Bernhardt knew every trick in the book to keeping herself in the public eye. So it comes as no surprise that she and Mucha came up with the poster below, which relied on her fame in order to sell Lefèvre-Utile cookies (known, thanks to Mucha, as LU).

Sarah Bernhardt/Lefèvre-Utile, Alphonse Mucha (1903)

Image c/o the Richard Fuxa Foundation

The image itself is a departure from Mucha’s signature style, created at a time when he wanted to transition out of the commercial sphere into that of fine art; however, it features Bernhardt in a Mucha-designed costume for one of her signature roles, posing beautifully for the viewer. Below, in perfect script, is her testimonial: “I haven’t found anything better than a little LU—oh yes, two little LU!” followed by her signature.

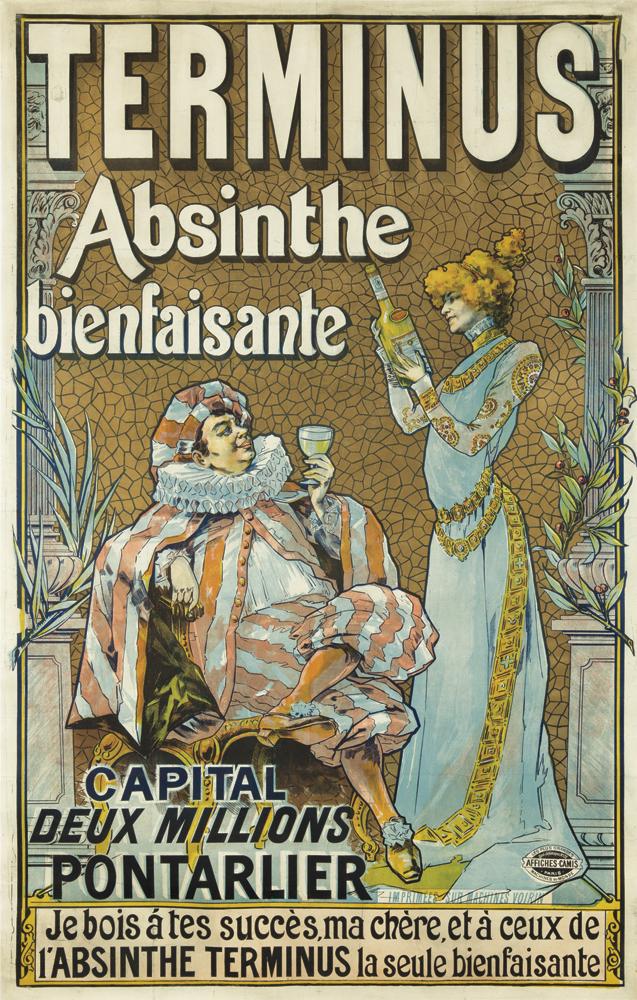

This is considered by most historians to be the first moment of an authorized celebrity endorsement on a poster. In fact, Bernhardt was so protective of her image after this moment that she sued any other company that used her likeness without her permission. The poster below for absinthe, for example, features her alongside another famous actor, toasting to their success. Not having paid either of them for this endorsement, Terminus lost the case Bernhardt brought to court against it.

Terminus, Francisco Tamagno (ca. 1900)

Image c/o La Belle Époque gallery

Finally, no one can analyze Mucha’s incredible posters without talking about the environments he created to promote products. More so than any other poster artist of the period, he had a knack for elevating an item above its pedestrian origins. Take, for example, another poster for Lefèvre-Utile and compare it to what the company was using prior to hiring Mucha.

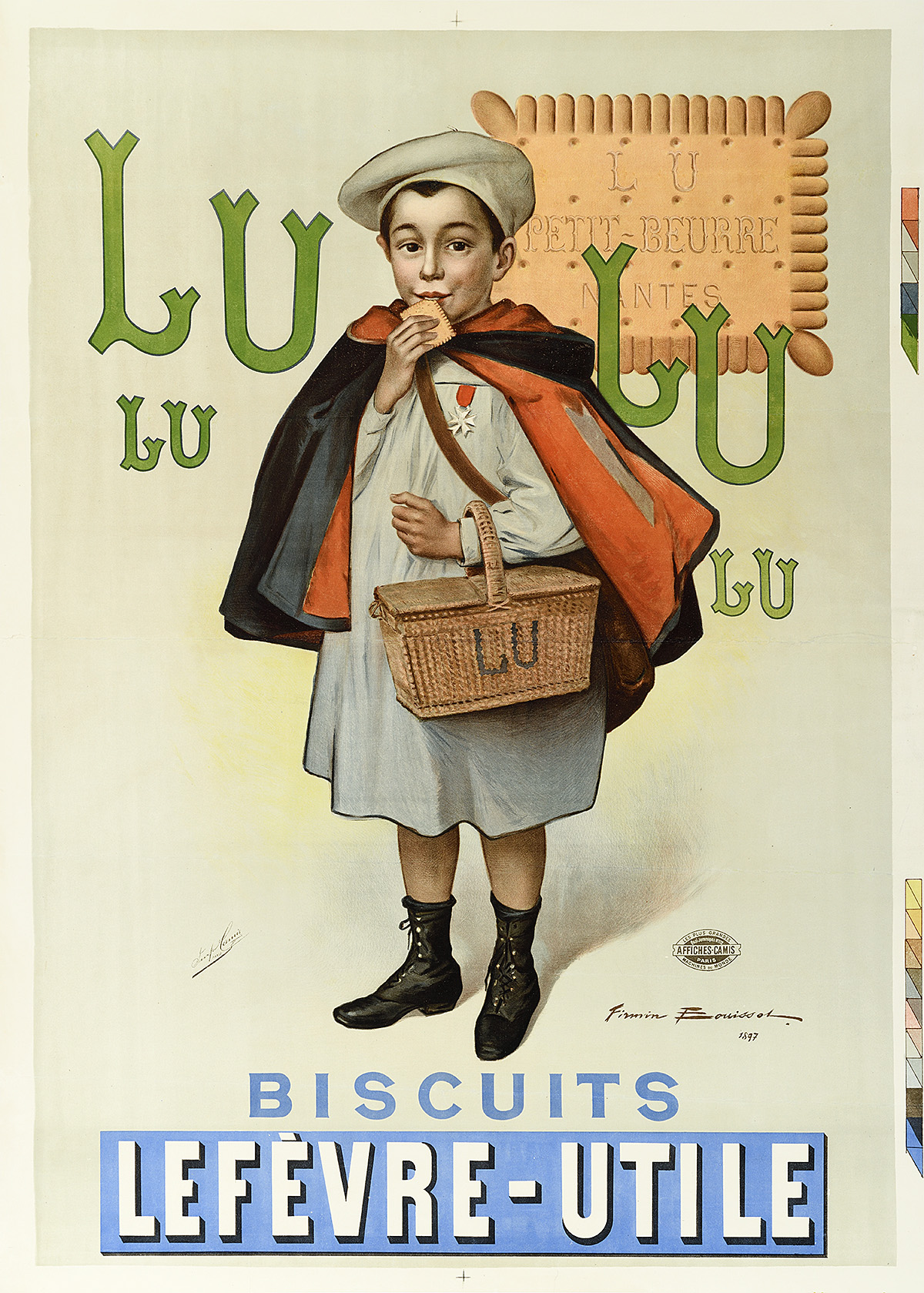

In the poster below, we see a boy in a private-school uniform with a medal for perfect attendance pinned to his cape. He holds the cookie and in the most straightforward of ways demonstrates that this is the treat of good little children in France. Mucha, however, takes that humble cookie from the lunch box to the opera box in his extraordinarily elegant poster for the brand on the right.

Left: Lefèvre-Utile, Firmin Bouisset (1897)

Poster House Permanent Collection

Right: Lefèvre-Utile Biscuits Champagne, Alphonse Mucha (1896)

Image c/o The Richard Fuxa Foundation

It seems simple, but no one had thought of doing that before. No one had bothered to create a world where the product wouldn’t normally be seen. Here, the simple cookie becomes associated with glamour, with society, with prestige—a go-to concept for pretty much any and all advertisers today.

This article was written based on information presented in Alphonse Mucha: Art Nouveau/Nouvelle Femme. For more information on that exhibition, please see our Past Exhibitions page.