Hot Poster Gossip: Uncle Sam Edition

Last year, our curator attended an event at The Museum of the City of New York, where graphic designer Mirko Ilic presented a lecture on where James Montgomery Flagg’s famous I Want You poster fit within the history of art. The story was so fascinating that Poster House asked Mirko if we could reimagine his talk for our Hot Poster Gossip! window series.

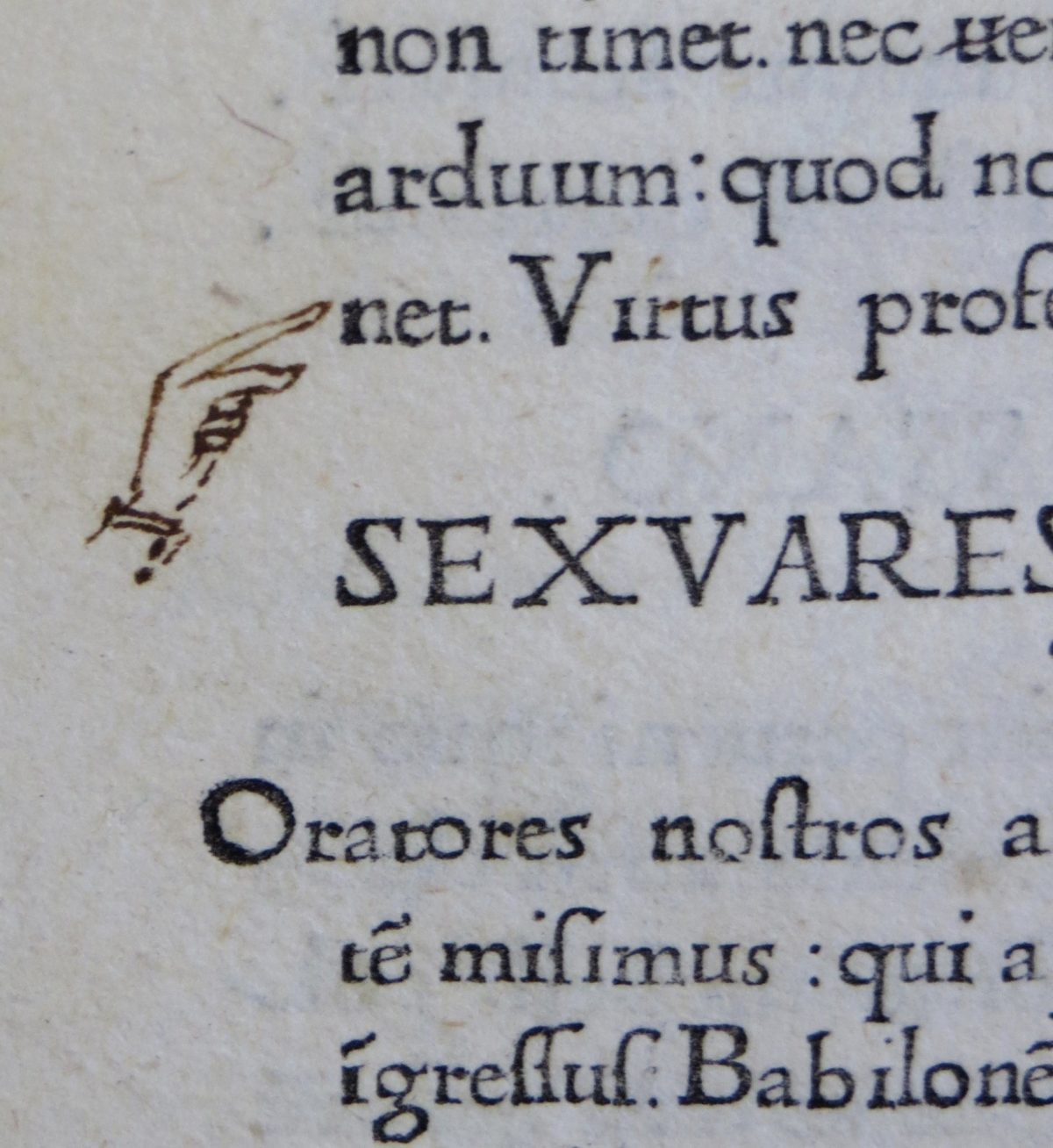

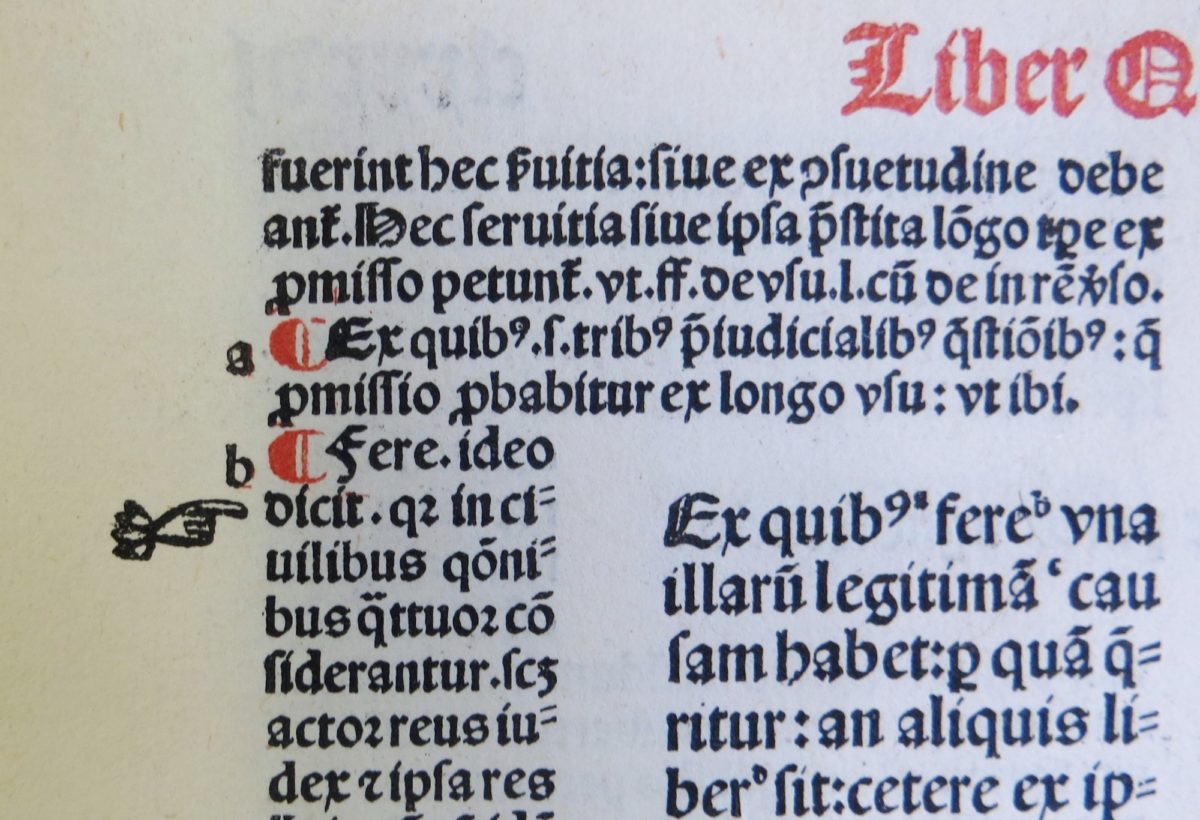

Details from books in the Special Collections and Archives, Cardiff University Library

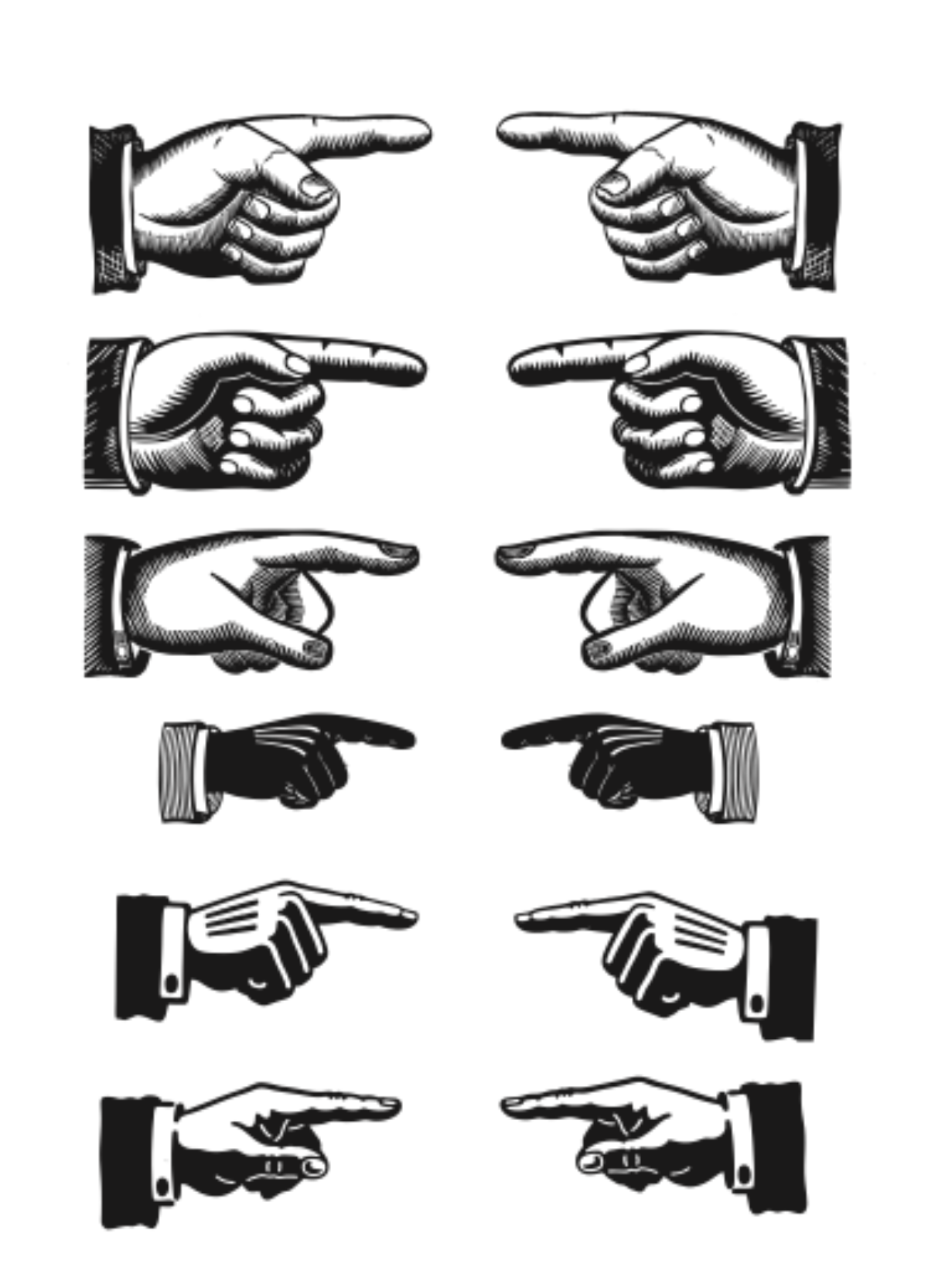

Before we can talk about Flagg’s now-iconic poster, we have to go way, way back to the days of illuminated manuscripts, when monks drew hands known as manicules next to important Biblical passages. These tiny hands weren’t just reserved for religious writing, though, as the oldest surviving example was created in the Domesday Book of 1086, a survey of landholdings in Britain commissioned by William I. These hand-drawn indicators would continue to appear in books up through the 18th century.

Examples of printed manicules

With the dawn of the printing press, manicules developed a more standardized form, and would continue to appear in books as ways of drawing attention to key passages. They also moved beyond the printed page into public signage, emphasizing everything from store names to dollar figures.

Portrait de l’artiste sous les traits d’un moqueur by Joseph Ducreux, 1793

In 1793, Joseph Ducreux – an artist known for his experimentation with gestures and expressions not normally seen in portraiture – painted this self-portrait wherein he is pointing at the viewer. This was the first time a figure did that in art. Moreover, it is interesting to note that the title indicates that Ducreux is mocking us – an important meaning behind a pointing finger which will appear again in the 1970s.

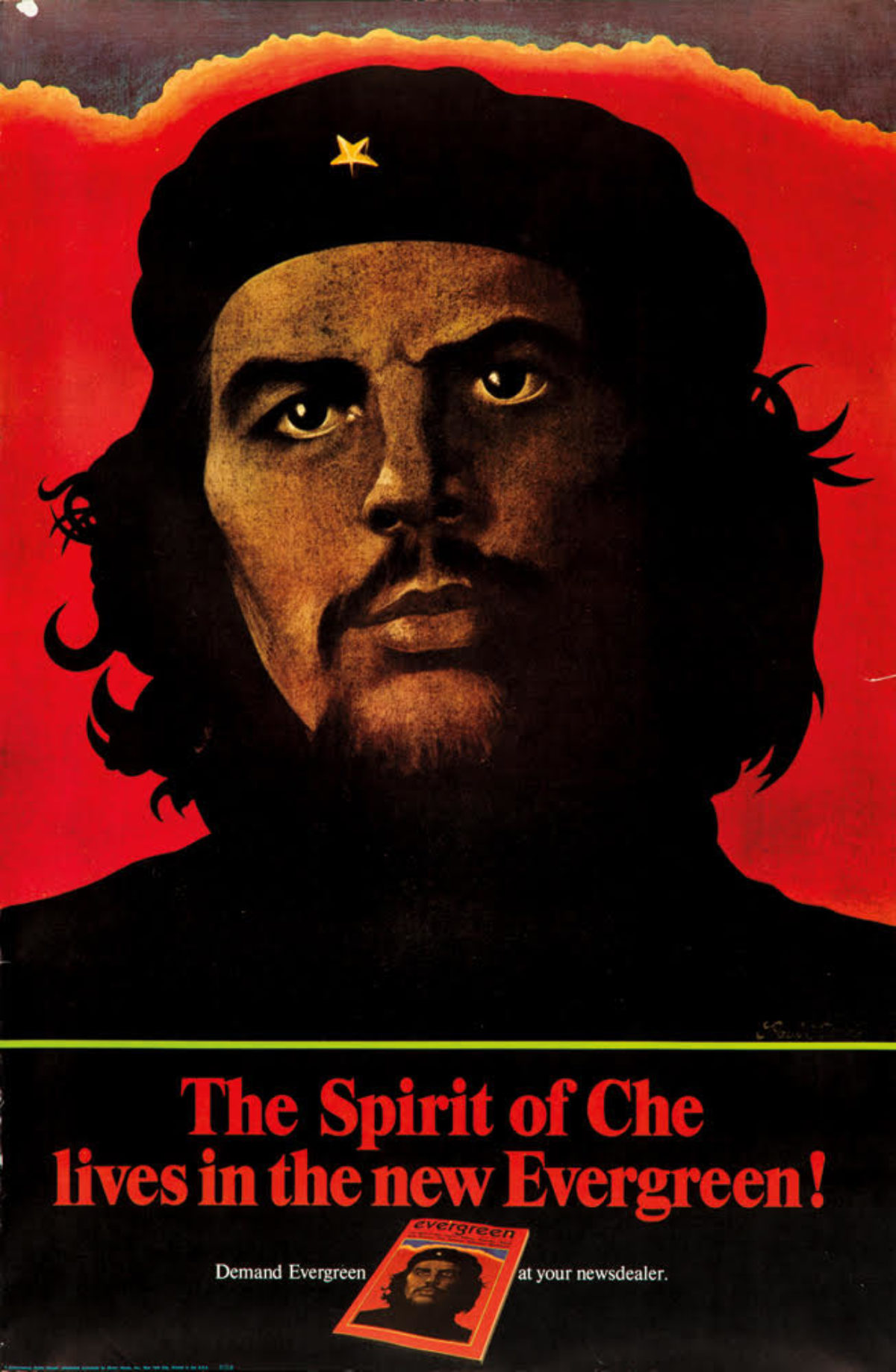

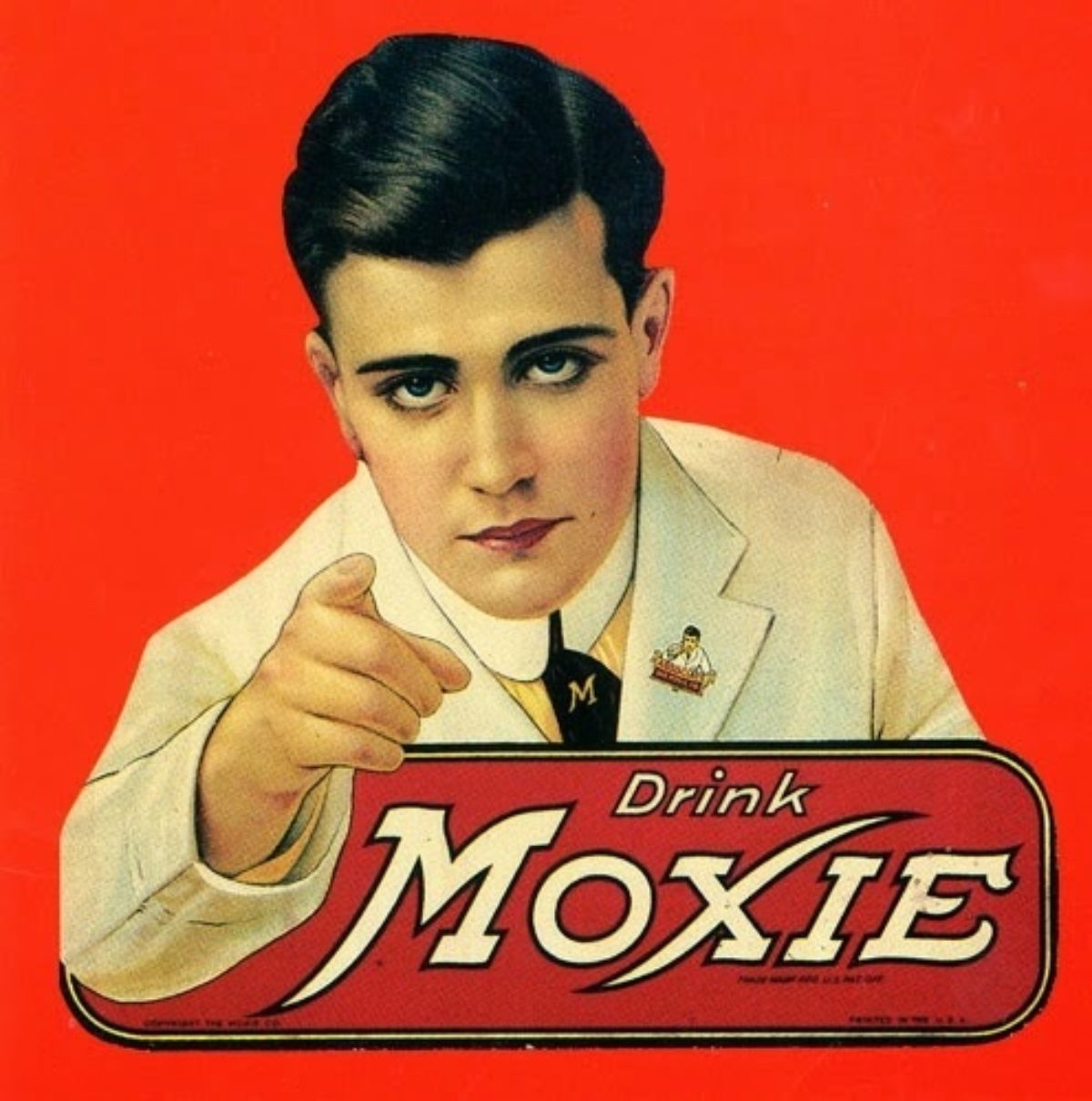

Moxie, ca. 1884

In 1876, Dr. Augustin Thompson created Moxie “nerve food,” a carbonated beverage still produced today. His decision to put himself on the label pointing at the potential consumer lends a sense of authority to the product – a doctor is indicating how important this beverage is therefore I should probably drink it.

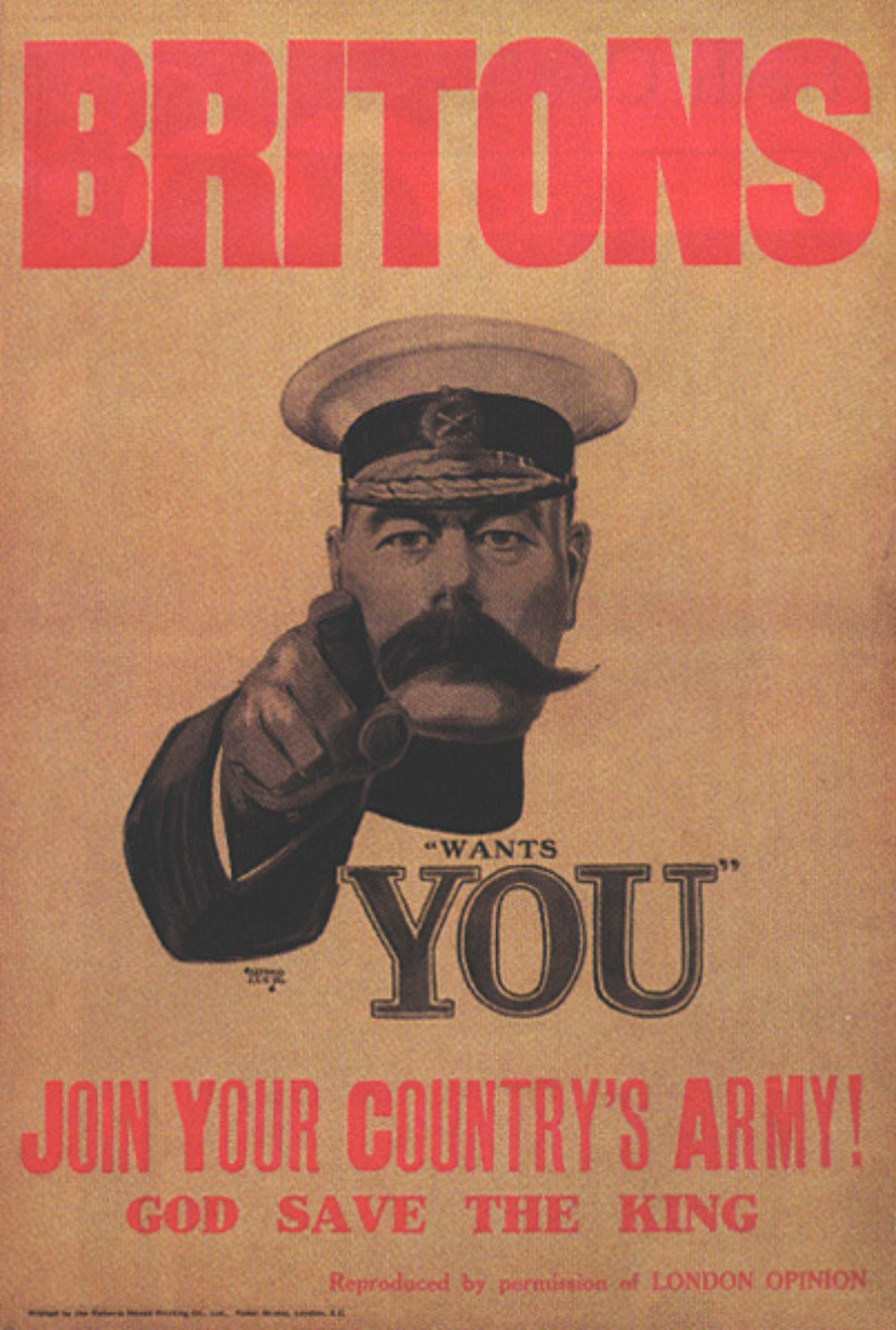

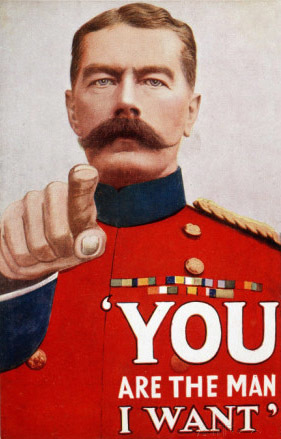

Lord Kitchener Wants You by Alfred Leete, 1914

And here is the image that launched a thousand posters: the first moment where a man pointing is explicitly asking you, the viewer, to take action. As the British Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener is asking you to join his army and fight the Central Powers at the outbreak of World War I. Since conscription wouldn’t go into effect until 1916, posters like this were essential to convincing men to enlist.

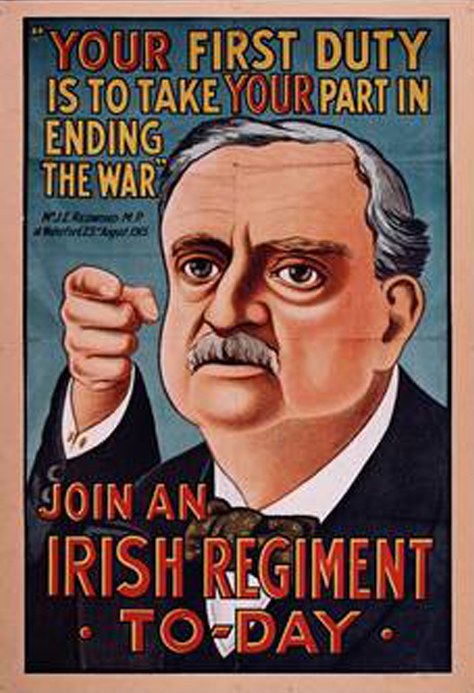

Almost immediately after Leete’s image of Lord Kitchener appeared, copycat designs cropped up throughout the British Empire, including these posters (above) featuring the Irish nationalist John Redmond as well as Canada’s own take on Lord Kitchener.

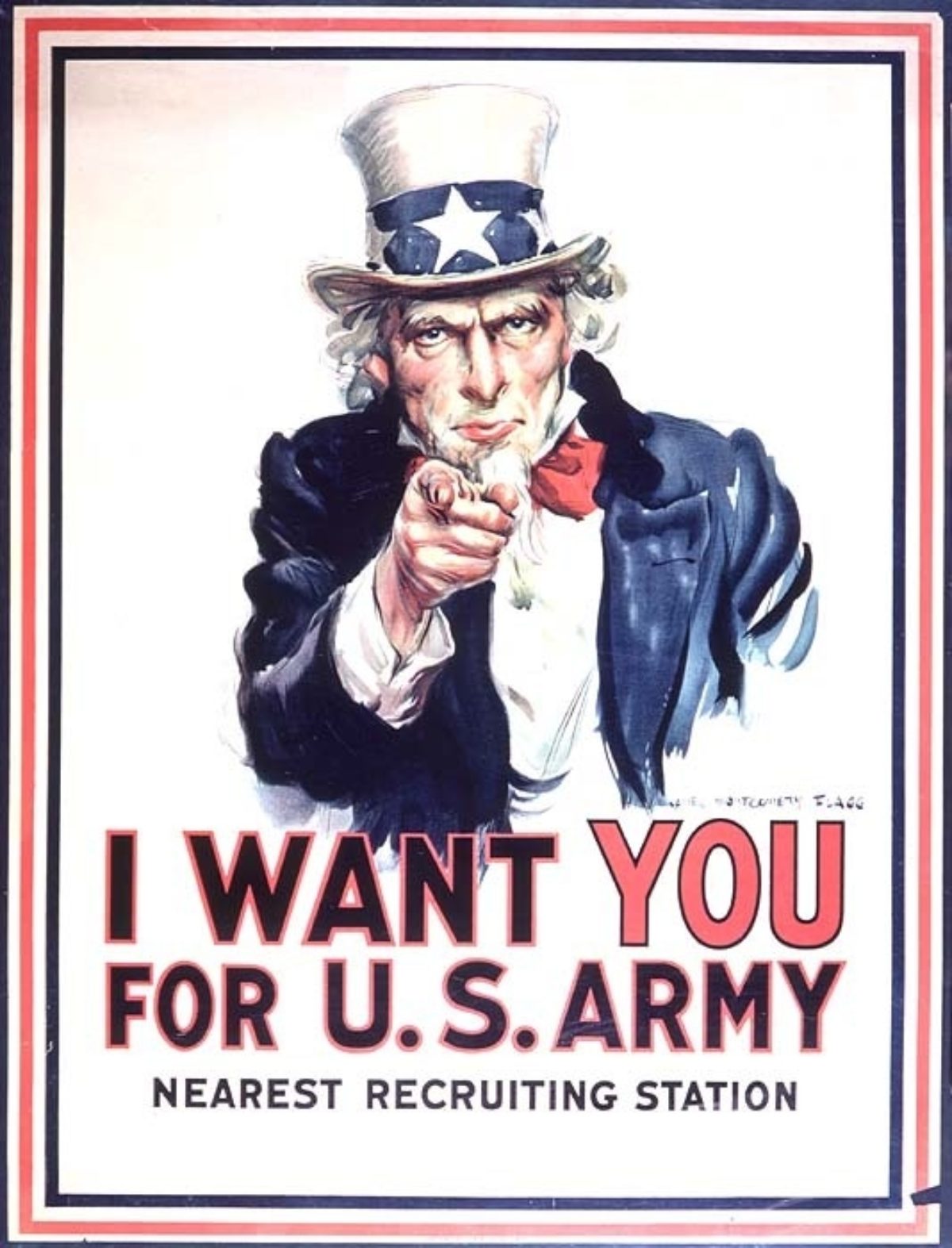

I Want You by James Montgomery Flagg, 1917

When the USA entered World War I in April of 1917, they, too, needed a recruitment poster. Taking obvious inspiration from Leete’s design, Flagg – the most famous illustrator in America at that time – replaced Lord Kitchener with a rendering of Uncle Sam. As Uncle Sam is not a real person, Flagg decided to base the portrait on himself, adding white hair and a goatee to make him more distinguished and authoritative. It would become one of the most published posters of the war, with over 4 million in circulation within the year. It would even make a brief reprieve during World War II when an additional million copies were printed.

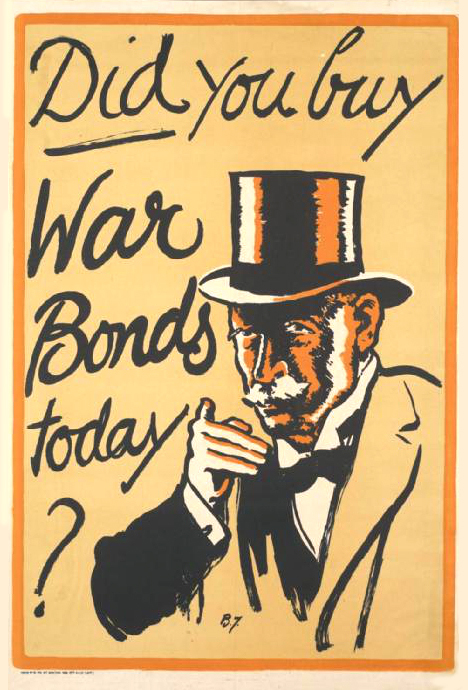

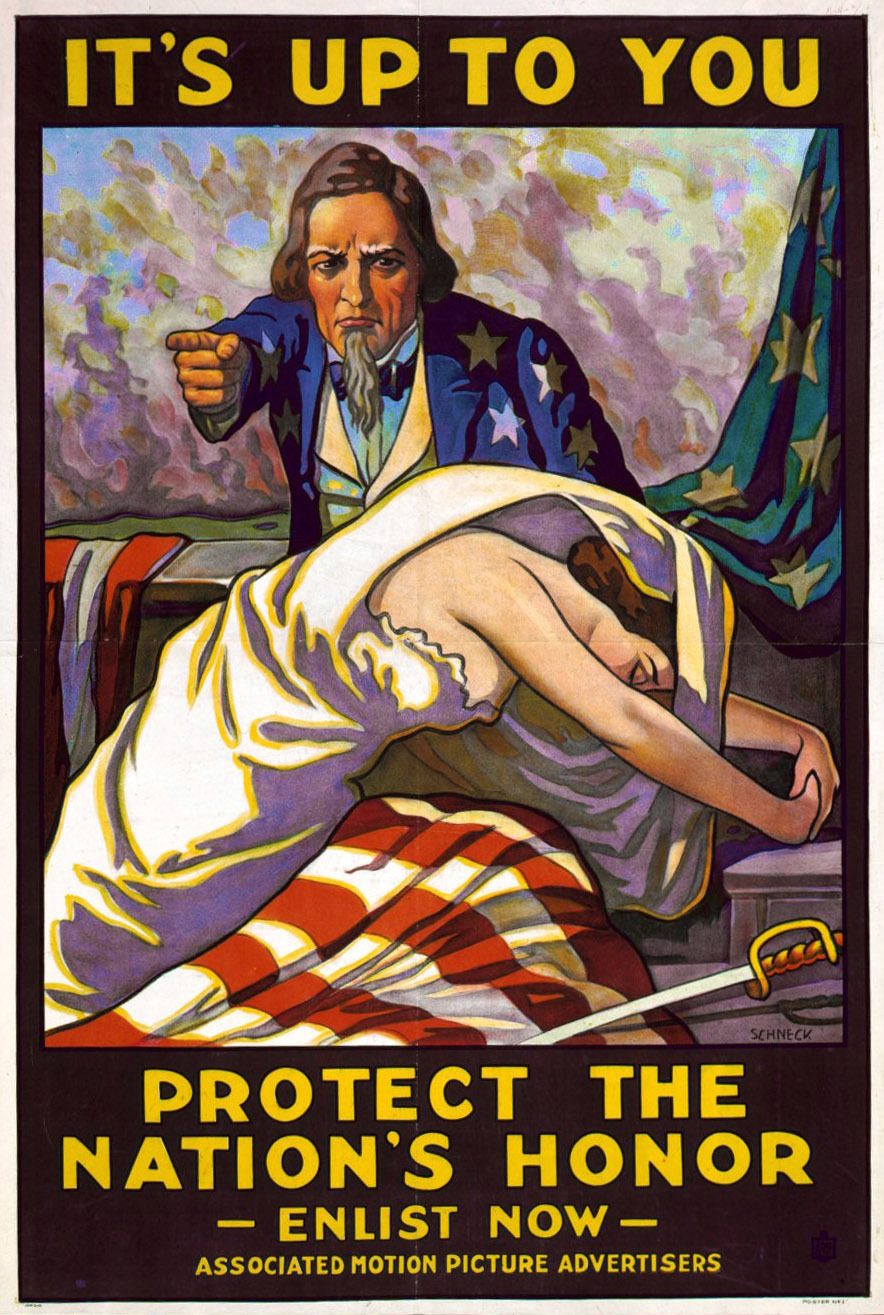

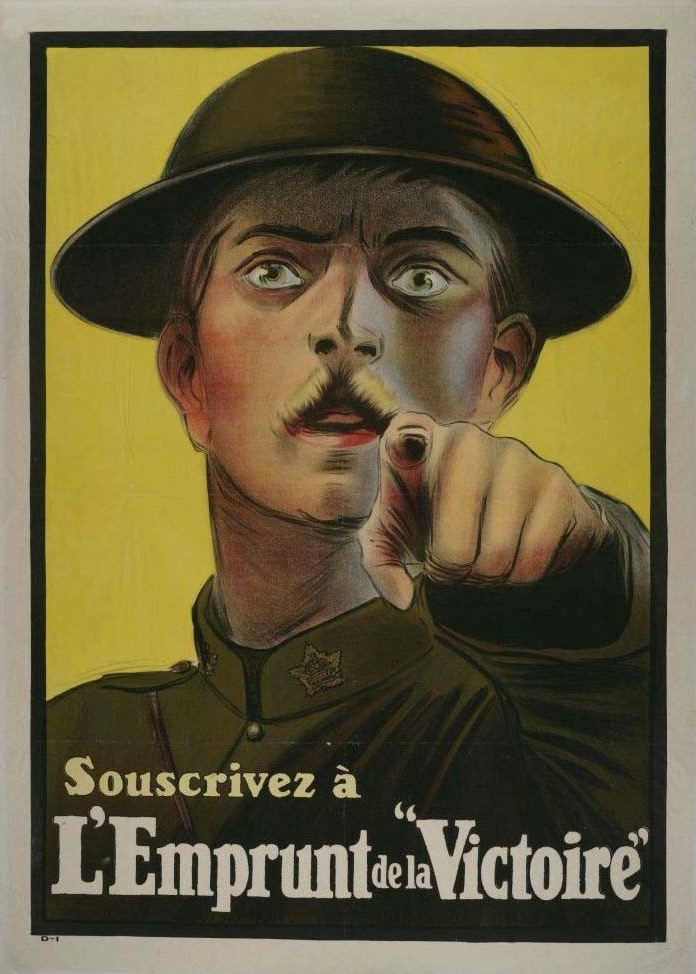

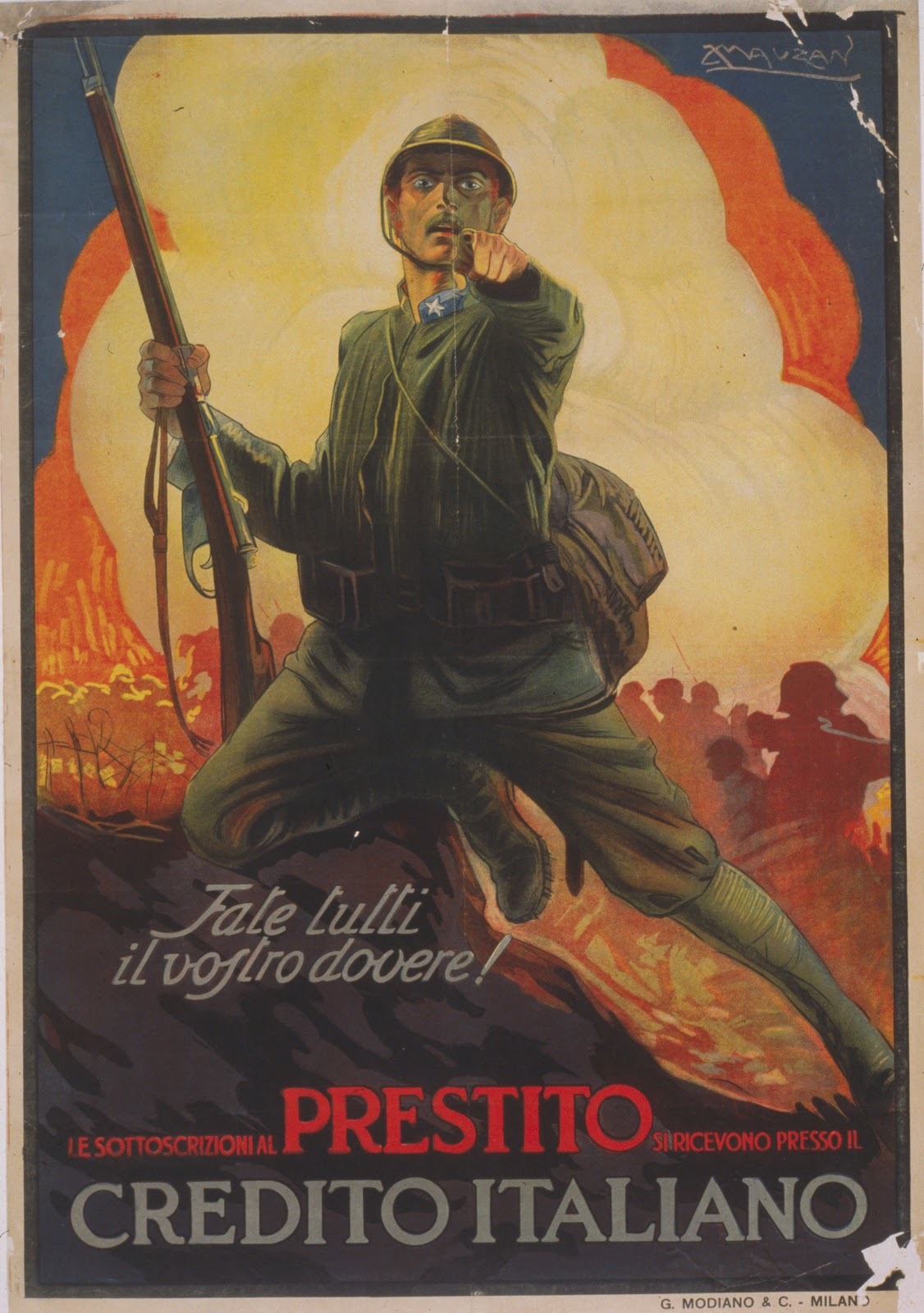

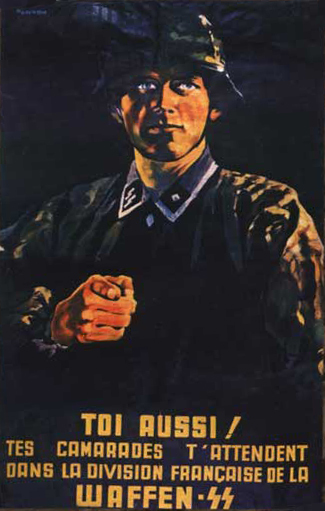

After Flagg’s poster became one of the most famous images of the War, other countries couldn’t resist appropriating the image of a pointing figure to drive their own messages home. When conscription went into effect and recruitment was no longer needed, the Allies and the Axis both used the pointing man to ask for financial support.

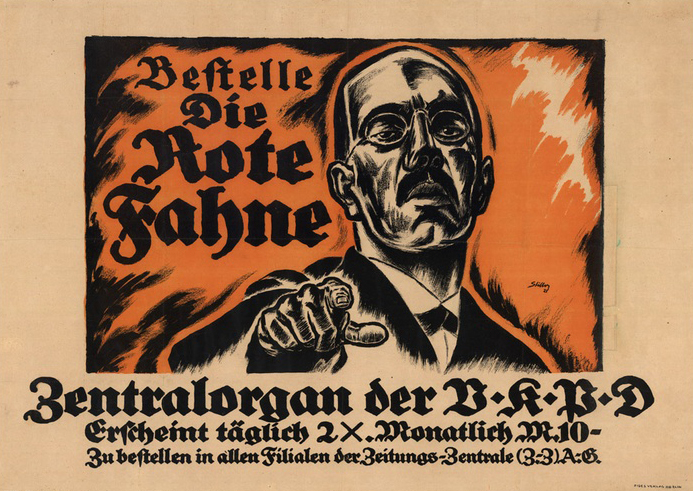

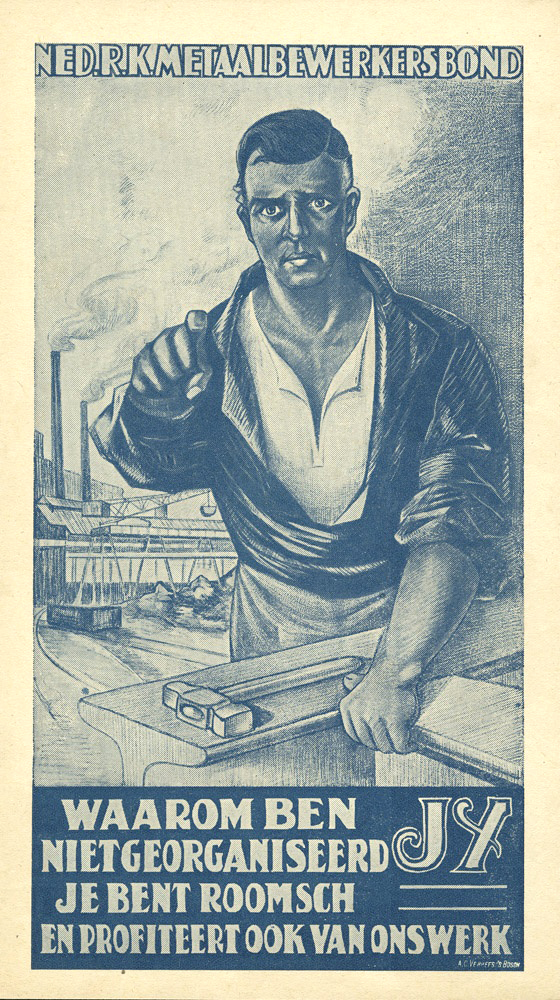

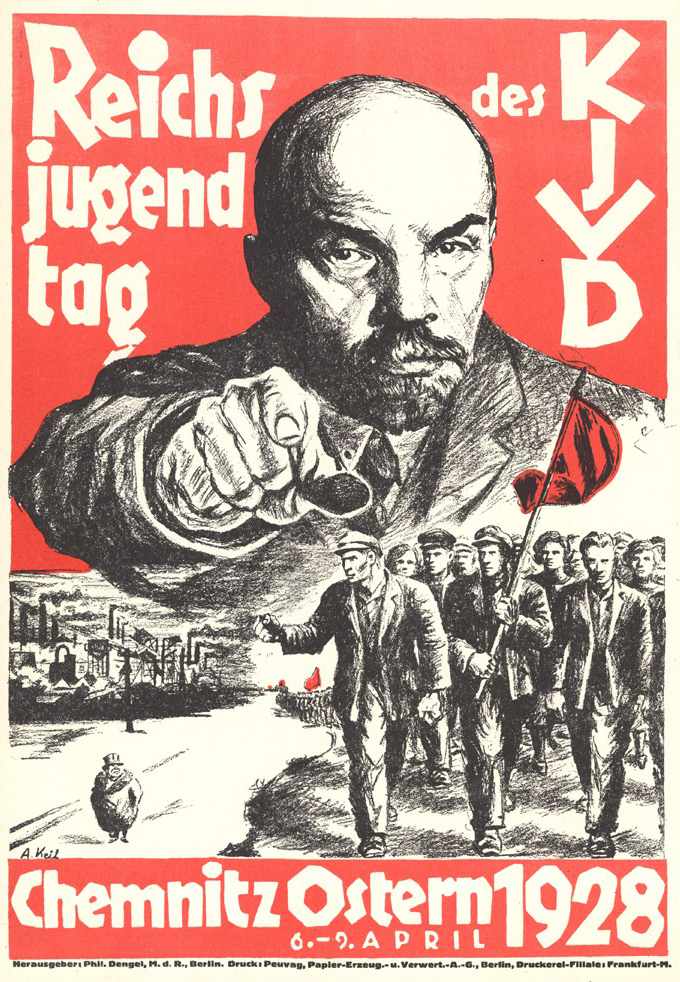

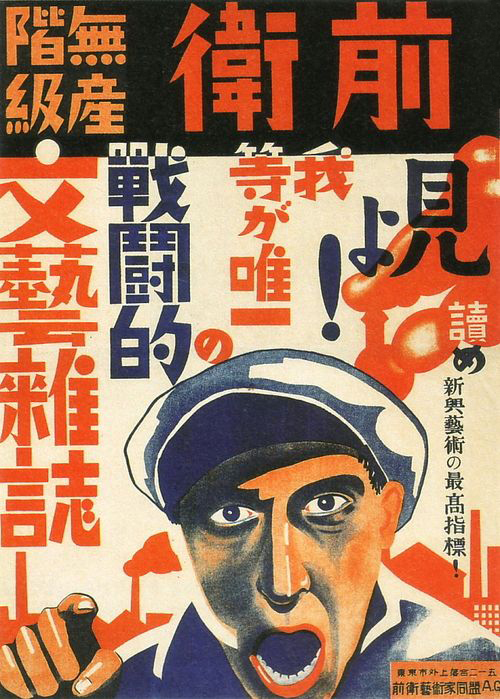

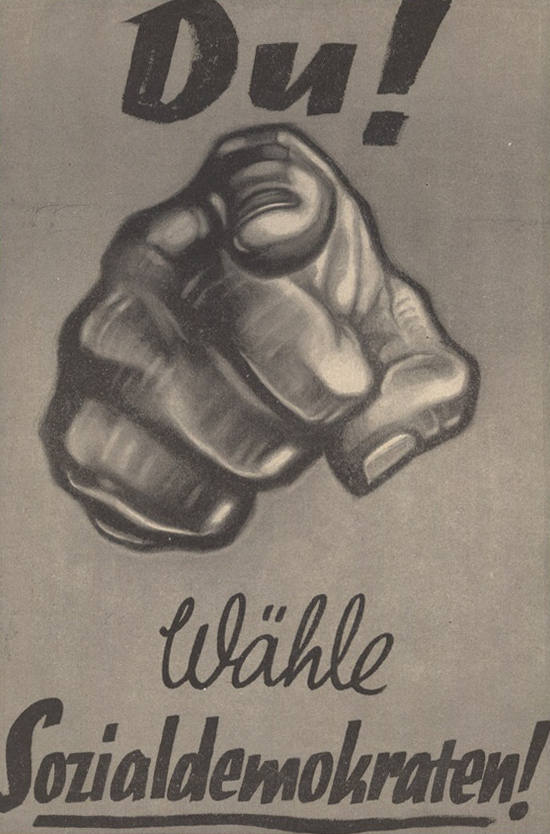

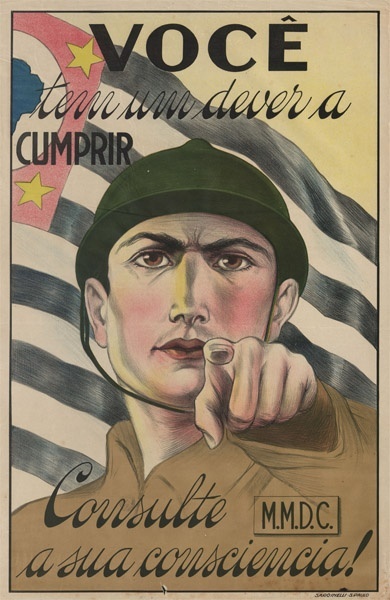

Even after the end of World War I, other causes continued to play with the trope of a man pointing at the viewer to lend an urgency to their poster design, from the Russian Revolution to the German Spartacus League’s political newspaper, the rise of the Japanese proletariat to the Spanish Civil War.

Along with Flagg’s poster being reissued during World War II, a new raft of finger-pointing posters appeared around the world, demanding that all citizens do everything they can to support the war effort.

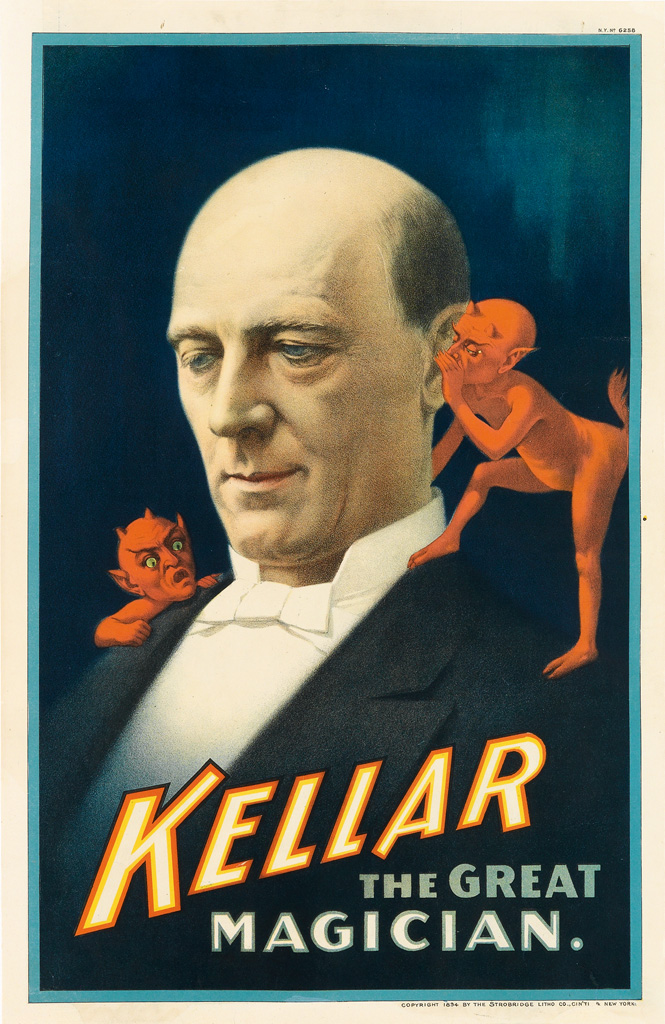

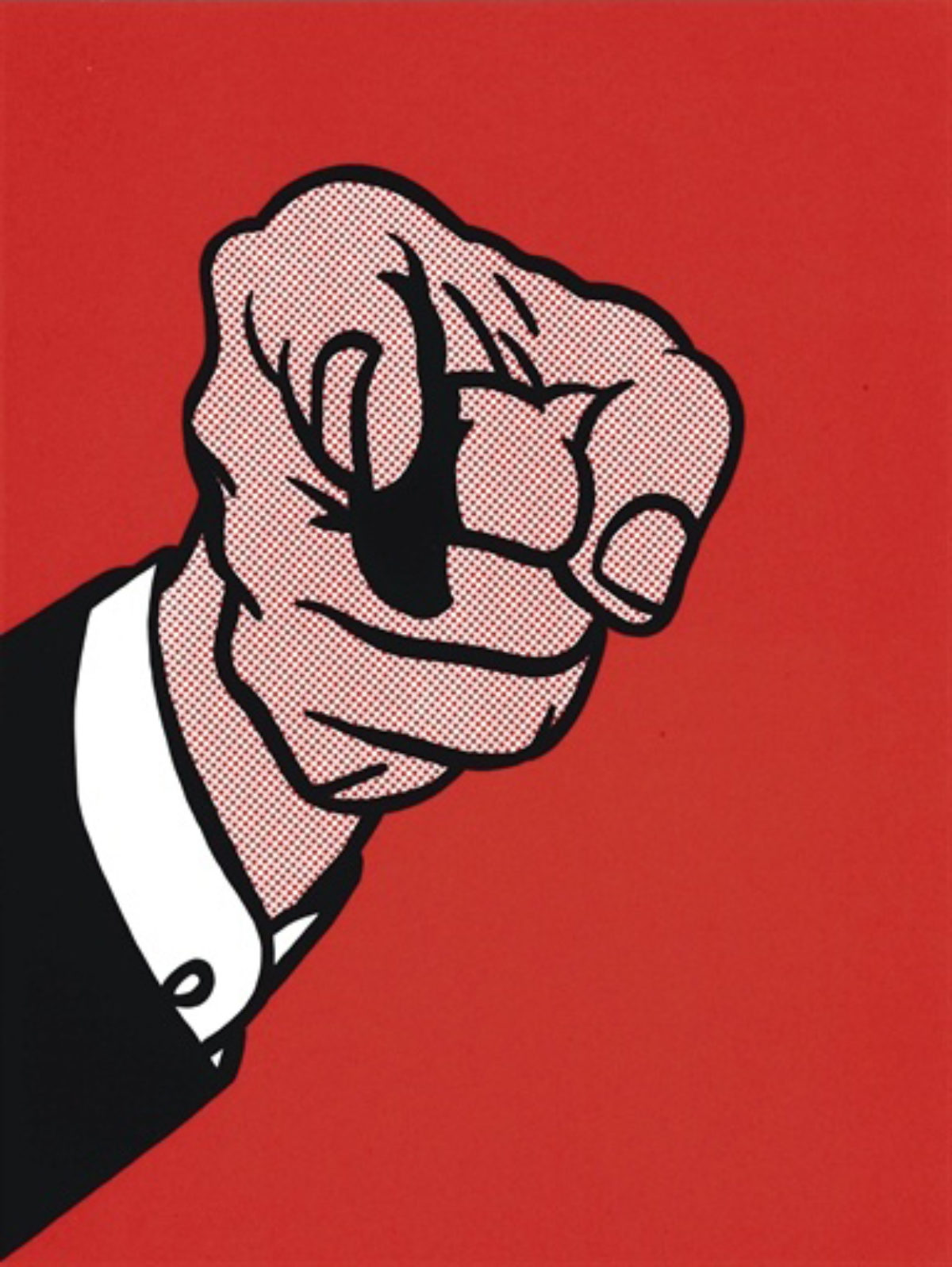

Finger Pointing by Roy Lichtenstein, 1973

Finally, in 1973, Roy Lichtenstein brought the pointing finger out from under the umbrella of war and into the commercial sphere, zooming in on Flagg’s hand of Uncle Sam and transforming it into that of an American businessman. The government would no longer be asking you to do all you can for your country, but rather to do all you can for Big Business – a dark-humored gesture tinged with the mocking air that Ducreux painted 180 years prior.

Poster House’s 23rd Street window displaying the history of the pointing finger

Poster House would like to thank Mirko Ilic for providing us with the images and ideas from his lecture. Further information can be found here.