Hisui Sugiura and the New Woman in Japan

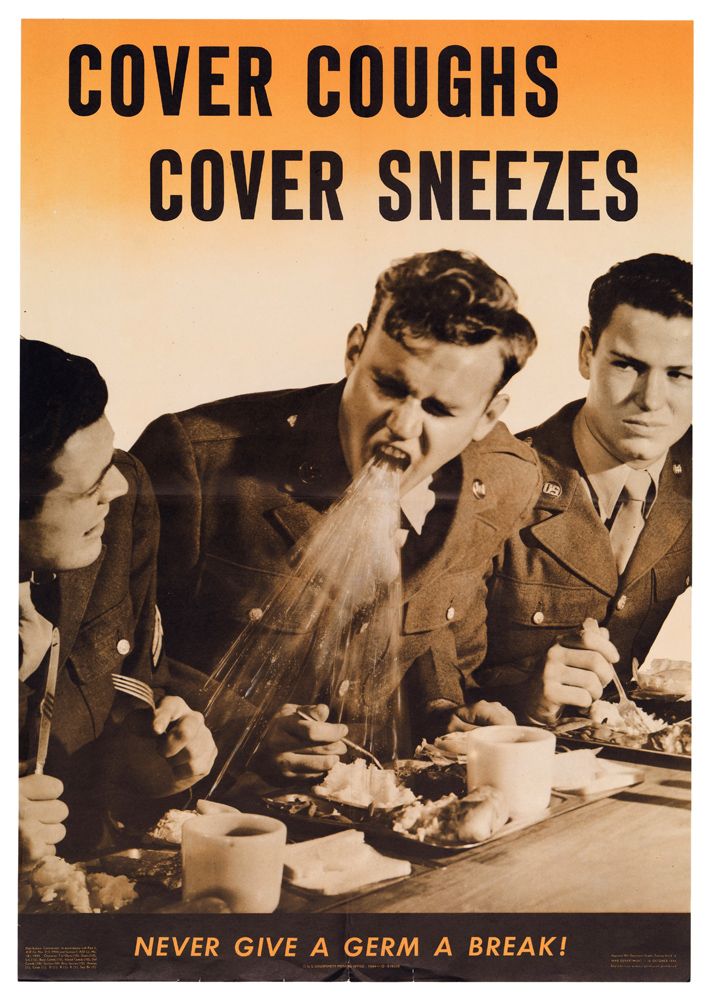

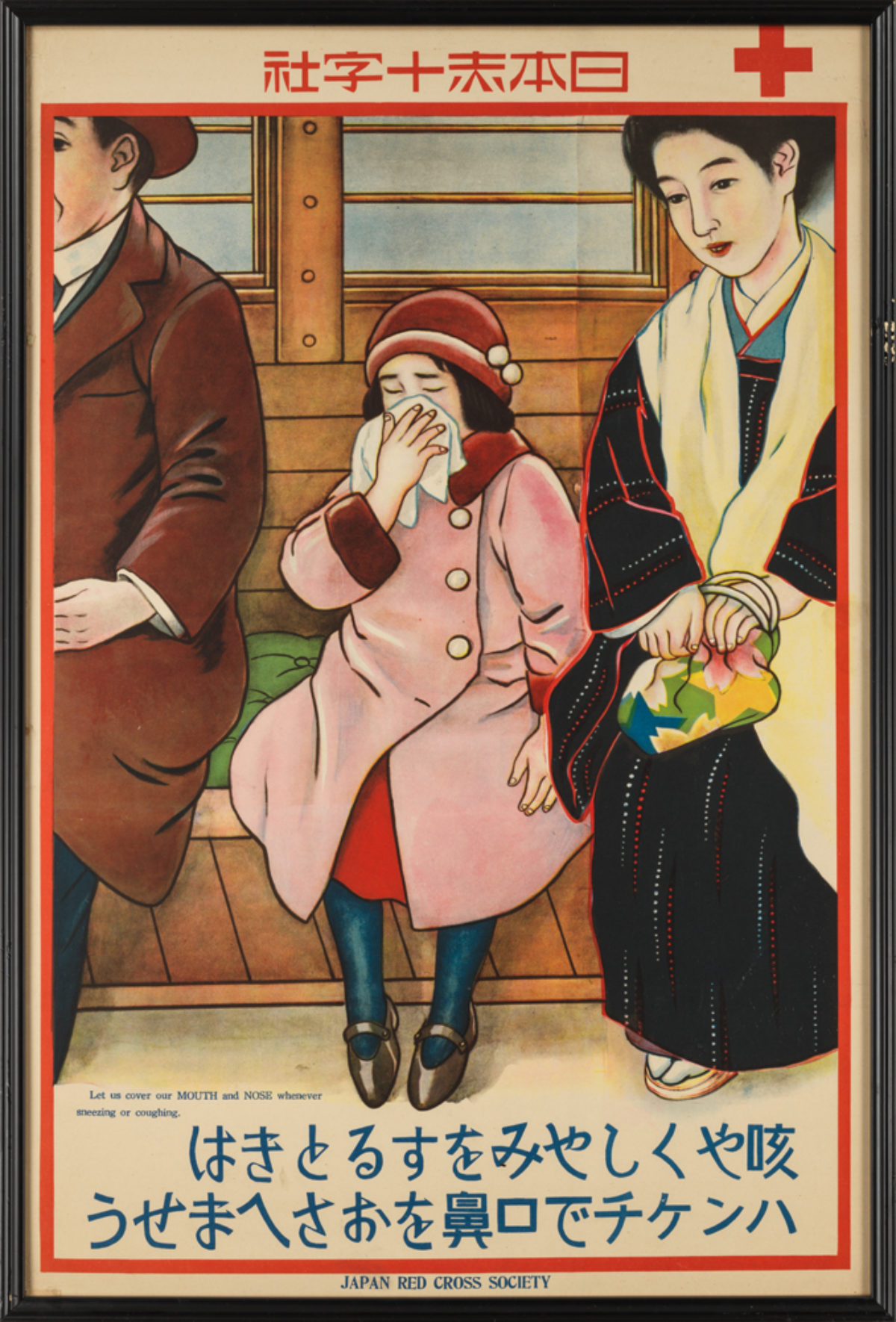

When visiting Poster House for the first time last fall, I had the delight of discovering their mini-exhibition Posters of the Japan Red Cross Society. These 1925 posters are educational and intended for children. In fact, they use children to teach other children habits of proper hygiene and health. In 1925, maintaining health was particularly important as the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic had only occurred some years before. Thinking back on these posters now, I am not only reminded of our current crisis with COVID-19, but also of the posters by Hisui Sugiura. However, Sugiura’s posters have to do more with another pressing issue of our time—the representation of women.

Japan Red Cross Society, K. Sakai (c. 1925)

Poster House Permanent Collection

The period in which these Red Cross posters were made is known in Japan as the Taisho era, spanning from 1912-1926. The Taisho era was one of great energy and social change—particularly for women. Sugiura, Japan’s first great graphic designer, made posters that captured this energy by incorporating artistic trends of the time, often featuring the “New Woman.” The New Woman, or atarashii onna, was a socially liberated, modern woman previously unseen in Japan. This type of woman was often characterized by her active lifestyle. No longer was she solely left to keep a home and family, but now she held down a job, got higher levels of education, and even entered into the political sphere.

Throughout Europe and America, the New Woman was taking over advertising (as seen in Poster House’s first exhibition Alphonse Mucha: Art Nouveau/Nouvelle Femme). Her development in Japan, however, remains distinctive against the backdrop of the previous Meiji era. The Meiji era spanned from 1868 to 1912. It was marked by rapid westernization and a motto of “civilization and enlightenment.” During this time, the Japanese government sought both to maintain their unique Japanese culture while also allowing for the integration Western thought. For this blog post, I would like to focus on the Japanese New Woman in relation to the establishment of the modern department store Mitsukoshi, her active lifestyle, and her role as a mother.

Mitsukoshi decked out for its grand re-opening (c. 1914)

(image c/o oldtokyo.com)

The Mitsukoshi Department Store

In Europe and America, department stores were pivotal centers for commerce, social gatherings, and innovative advertising. While Western department stores catered to the middle class, Japanese department stores worked to cultivate one who embraced Western ideology and products. As Japan’s first modern department store, Mitsukoshi symbolized modernity and was a Japanese tastemaker. One facet of this modernity was Mitsukoshi as an artistic center for the viewing and even production of art.

Mitsukoshi opened a design department in 1895. Both students and graduates of nihonga, traditional Japanese painting, were hired. During the department’s early years, the nihonga style served a dual purpose: creating art to satisfy a Western market’s idea of Japanese-ness and as a nostalgic reminder of the past for the local Japanese. Throughout the years, however, Mistukoshi began to embrace Western styles and the idea of “fine art,” known as bijitsu, and began producing it. In 1908, Sugiura was appointed the head of Mitsukoshi’s design department and played a role in bringing modern and Western-influenced design to the store.

Left: Mitsukoshi with the Murai Bank in the foreground (c. 1914)

Right: Art Exhibition in the Mitsukoshi Store (c. 1905)

(images c/o oldtokyo.com)

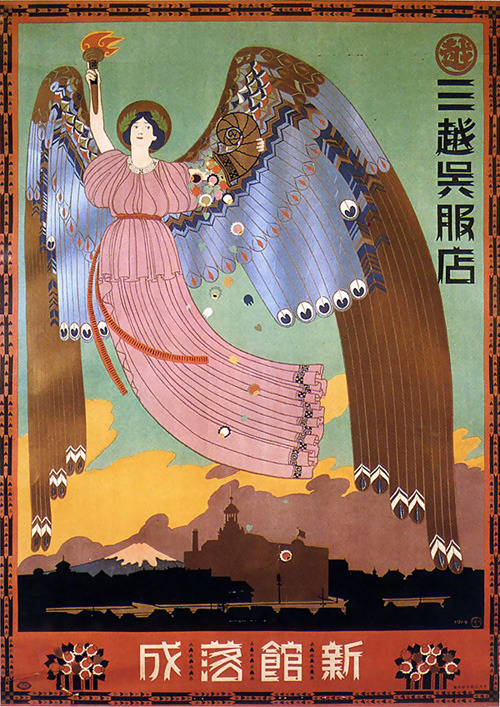

Sugiura designed a series of posters for Mitsukoshi which went beyond a singular beautiful woman selling products, known as bijing-ga, pulling from a variety of modern art movements and ideas. The two posters below borrow tropes from the Art Nouveau movement, which was especially popular throughout Europe at the time. In the first, much like the European artist Alphonse Mucha, Sugiura features an angel-woman in a flowing robe above the skyline of Tokyo. Geometric patterns build on each other to make up her wings along with peacock-like feathers. Both of these features are common Art Nouveau motifs. Moreover, the angel giving the blessing of enlightenment on the city of Tokyo appears as a modern woman herself.

The second poster is a sort of fantasized idealization of the modern woman as a moga, or Japanese flapper. She poses, balletic, anthropomorphized into a hybrid of butterfly and woman—a sort of fairy in a garden. This flowing posture would have been a mark of the Art Nouveau movement. Also noteworthy, this woman isn’t in a kimono. Her style actively displays features taken from the West. Her hair is bobbed. She is wearing a flapper dress. This would have been the beginning of a modern image of women in Japan.

Left: Mitsukoshi Department Store, Hisui Sugira (c. 1914)

Right: Mitsukoshi Gofukuten, Hisui Sugiura (c. 1915)

(images c/o Tumblr)

Sugiura’s designs evolved into the Jazz Age of the 1920s and throughout the 1930s, embracing the sharp angles of Art Deco. Below, the 1925 poster on the left shows a woman in a modern kimono, still somewhat embracing the curves of Art Nouveau. Her kimono matches her cropped haircut and small black purse. Likewise, the little girl, presumably her daughter, wears a baby doll dress and hat. Both of their fashions are a step into the future. The mother and daughter walk away with the backdrop of a crowded Mitsukoshi department store building, much sharper in contrast to their curving dress.

This emphasis on the building itself carries on into the next decade. One can see the sharp lines of the Art Deco Ginza branch in the poster on the right from 1930. Even the figures themselves are primarily composed of straight lines. The lights aglow in the fading daylight of evening, this poster was used to advertise the opening of a new branch. What an event for women and children in their best Mitsukoshi attire.

Left: Mitsukoshi Department Store, Hisui Sugiura (c. 1925)

(image c/o Georgetown)

Right: Mitsukoshi Department Store: Ginza Branch, Hisui Sugiura (c. 1930)

(image c/o Tumblr)

The Atarshii Onna and Her Active Lifestyle

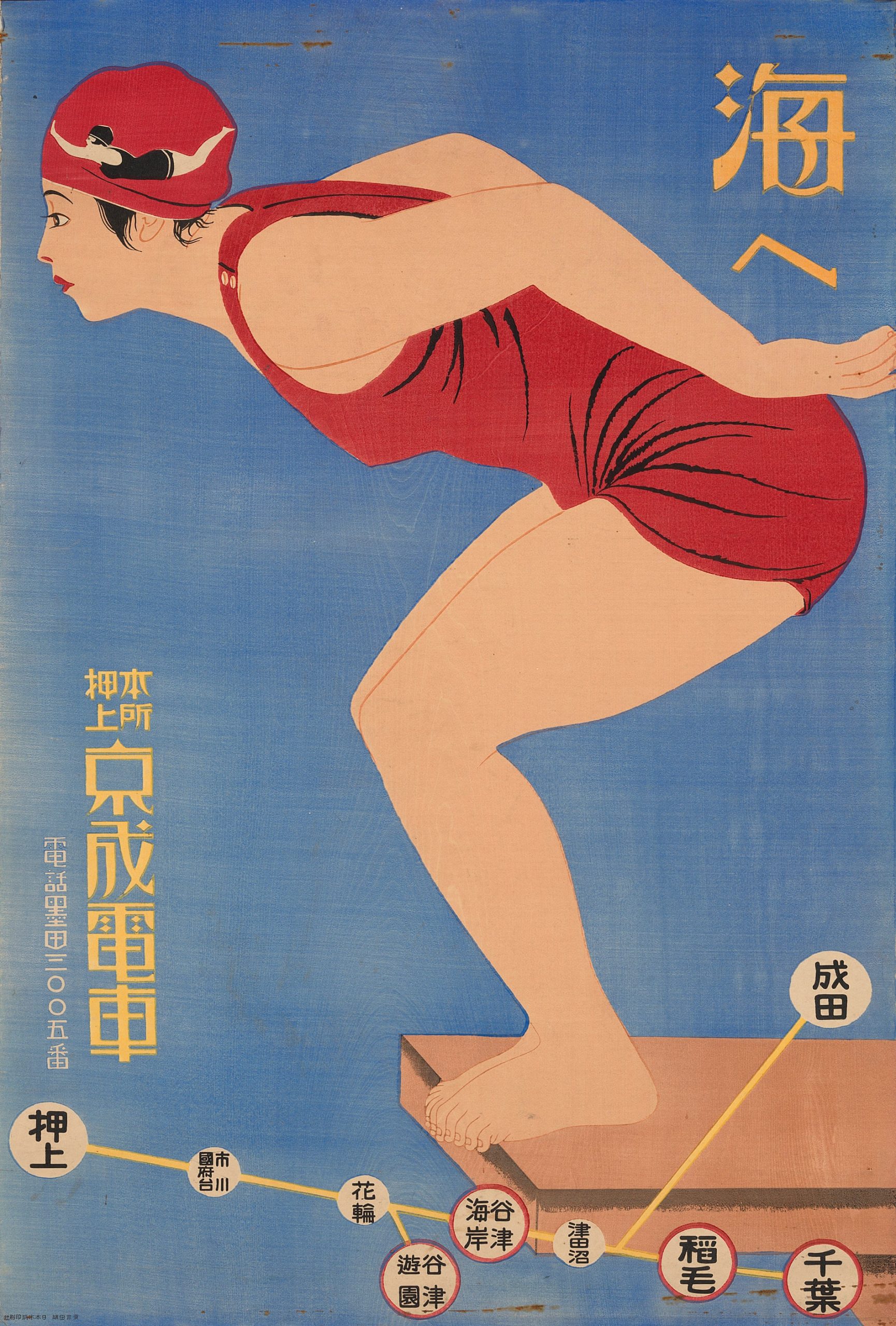

The atarashii onna was marked by her preference for traveling around town and elsewhere, and living an active lifestyle. These women were shown in posters and prints skiing, sightseeing, dancing, and swimming. Activities like this portrayed a newfound freedom beyond the home (many artworks depicting these actions are included in the National Gallery of Victoria’s upcoming show Japanese Modernism).

Outside of working for Mitsukoshi, Sugiura designed posters like the one from 1927 below for the first subway in Asia. A crowd of people anxiously wait on the edge of diagonal platform, dividing the frame in two. Some are dressed traditionally and others in modern wear. Near the front, a woman in a long red overcoat, cloche hat with ribbon, and tight cropped haircut, turns to speak to her male companion. He is wearing a Stetson hat, gloves, and smoking a cigarette. The couple is the epitome of Taisho cool and style, though the inclusion of those wearing kimonos in this time also shows a uniquely Japanese modernity and identity. Moreover, everyone on the platform, young or old, is taking part in a new Japan—one that includes an even faster way to get around.

Left: To the Sea, Shaboano Kiyosaku (c. 1930)

Right: The First Subway in the East, Hisui Sugiura (c. 1927)

(images c/o The Guardian)

The Atarashii Onna as Mother

While I have long been interested in the representation of women in these posters, the inclusion of children has begun to catch my eye, and I have started to think about what this means in light of motherhood. During the Meiji period, the idea of “good wife, wise mother” was the prevailing government sentiment on the role of women. Women were meant to raise good citizens for the state. To do this, one must be a “good wife”: raising children, keeping a home, obeying your husband. She must also be a “wise mother,” an Enlightenment-era idea from the West that mothers should be educated enough to raise children properly. Though many of these posters are post-Meiji, that ideology still stands strong in a more traditional sense. Indeed, Mitsukoshi, as an institution cultivating middle class taste, seemed to be one geared toward a fashionable motherhood.

Looking back at the Japan Red Cross Society posters in light of “good wife, wise mother,” the absence of actual mothers is palpable. As mentioned in my first paragraph, it is very much children teaching children. More than anything, perhaps this absence is a mark of the changing times. Mother is out of the house, so you must take care of yourself—a stark difference from Sugiura’s Mitsukoshi posters. In one of these posters, a little girl sits on a train with a handkerchief. The role of the woman next to her is ambiguous. She is close to the girl yet does not seem to engage with her actively. Is this her mother or simply another passenger?

Though the children are on their own in these posters, they are not without supervision—whether it be their peers, older siblings, or the government. In light of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, it is as if these posters are saying, “In times like these we must all take responsibility for ourselves. Keep clean, stay polite, and exercise.” Now, in the time of COVID-19, these posters are just as relevant as they were then. Equally as relevant today, Suigiura’s representation of women comments on the changing position of women. One continues to ask: how have we progressed and how have we stayed the same?

Sarah Sloan is a Shop Associate at Poster House. Enthralled by the designs and sumptuous curves of Alphonse Mucha, Sarah began her exploration of posters during her graduate studies at the University of Florida and has been learning ever since. She enjoys Japanese art and anime and has taken a particular interest in Meiji/Taisho period graphic arts. Her favorite part about working in the Shop is guiding visitors to new artists, ideas, and movements through its vast selection of books.