A message from Our Curator

There is no official list of every museum in New York City. Some websites say as few as 83 museums operate in the five boroughs, while others claim the number is closer to 113. I’ve even heard someone say there are over 400, but that seems a bit high even for a cultural mecca.

Yet, while there are museums dedicated to math, taxidermy, tattoos, finance, and sex – not to mention an impressive number of household-name institutions like The Met and MoMA – there has yet to be a museum focused on the art of the poster.

More so than any other form of art, the invention of the color print, and subsequently the poster, revolutionized the way the public could interact with a decorative visual medium. Prior to the color print, high art was reserved for the elite. Paintings were expensive and seldom seen outside of salons or the homes of rich people, meaning that for the common man the only real place he or she could see public art was in a church.

Prints came along and allowed the middle class to decorate their homes with fashionable and attractive images, but it wasn’t until Chéret’s posters in the 1880s that everyone and anyone could encounter a virtual art gallery simply by stepping outside.

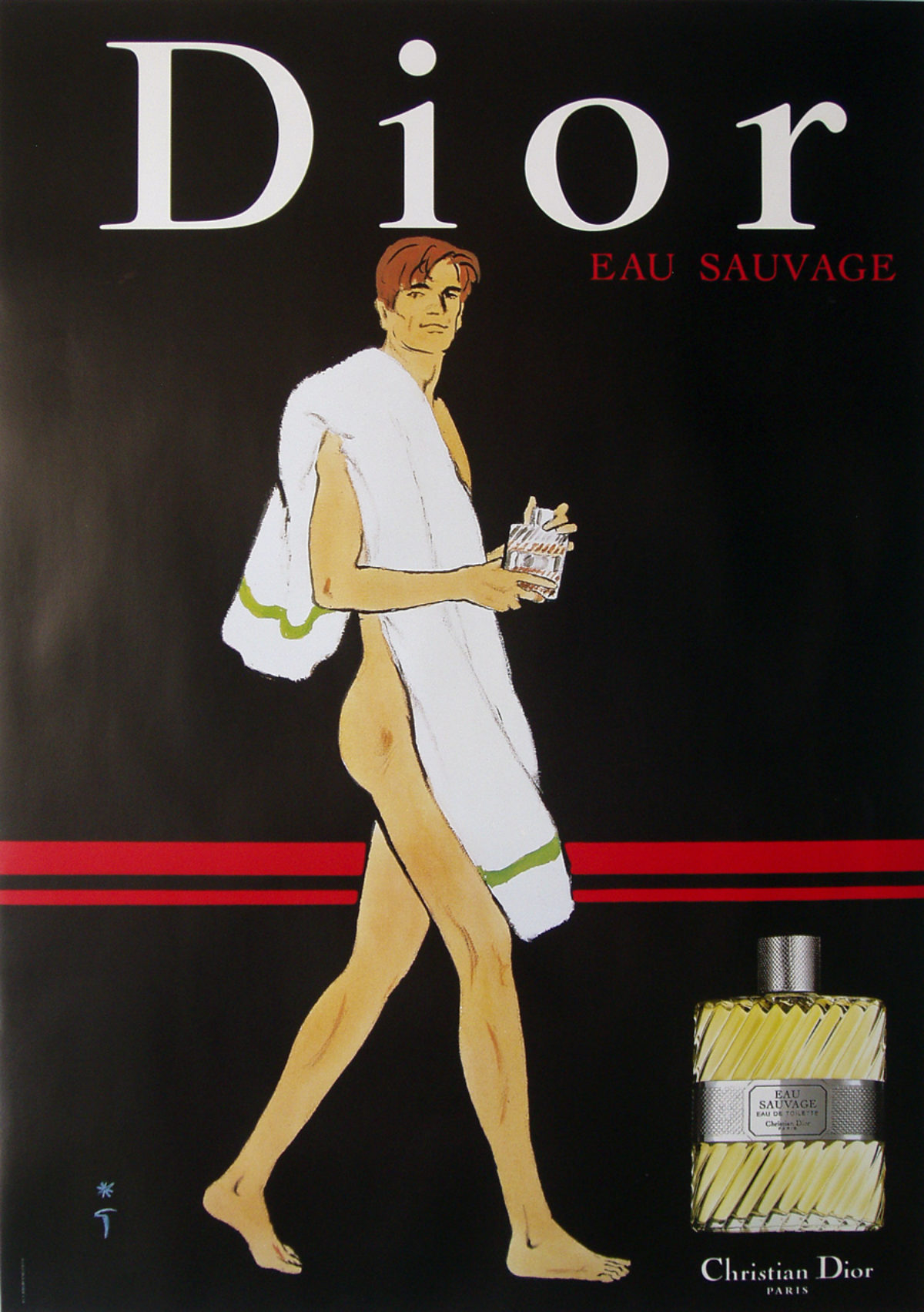

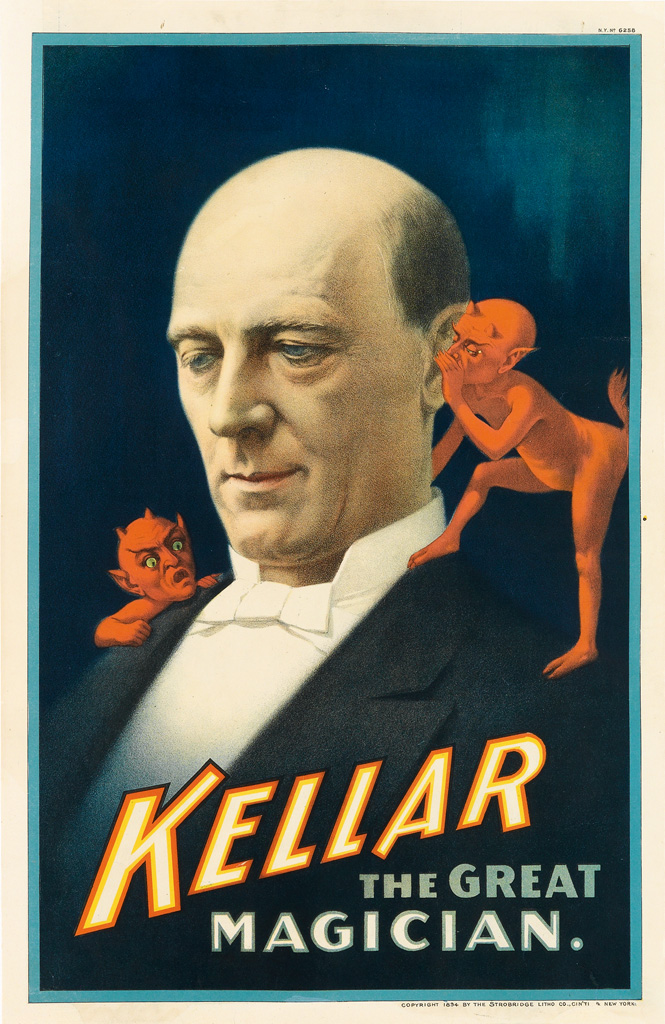

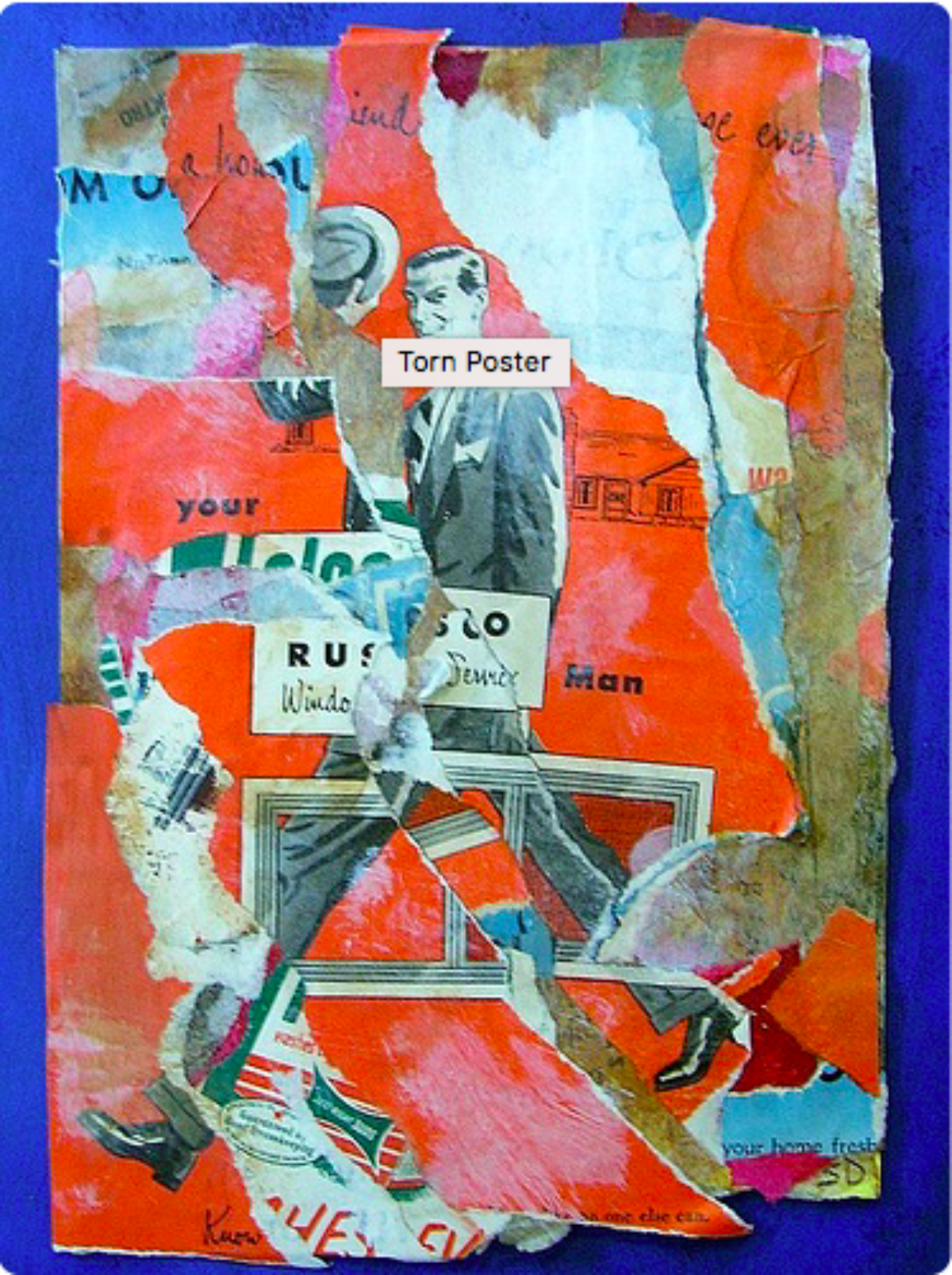

The poster brought lush visuals and flashy colors to the street, democratizing it, secularizing it, and placing it in a position where it neither needed to be venerated or academically studied to be appreciated. Dealers began opening shops around Paris, international exhibitions were formed, and magazines dedicated to cataloguing and discussing every new poster design were printed with enthusiastic subscribers from around the world.

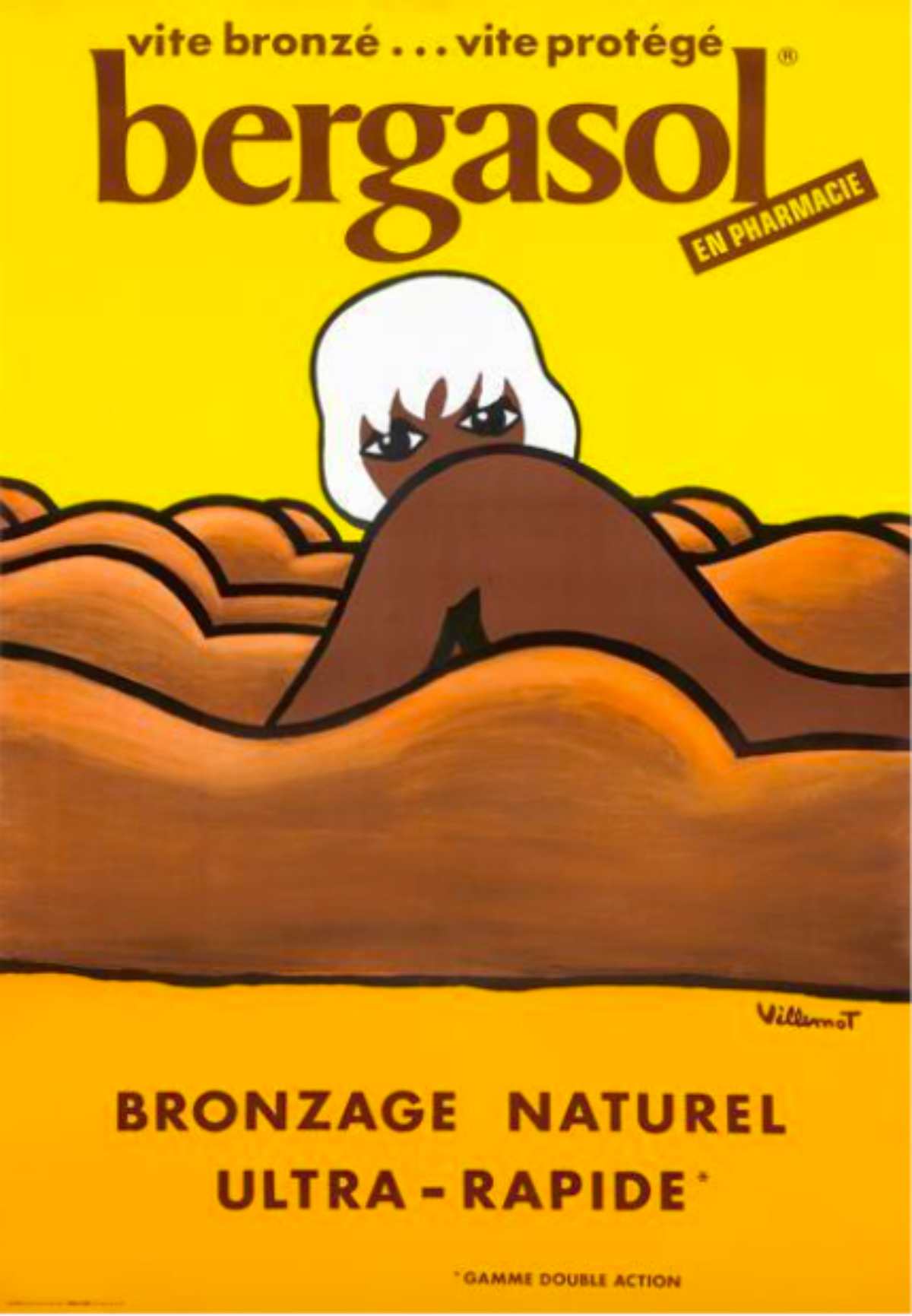

Looking at the general history of the poster, it managed to translate every major Western art movement (Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Expressionism, Modernism, et al) into consumer media. And yet, it didn’t simply bring those movements out of an elite space into a more neutral one – it took the key signifiers of whatever “high art” was in fashion, and filtered through the lenses of folk art and mural painting, creating something particularly new and unique. This was the people’s art.

How does such a game-changing medium, then, not warrant its own museum?

Poster House is going to change all that.

I spent the last decade of my career studying posters. That’s over 300,000 hours of touching, examining, authenticating, researching, and writing about posters. And let me tell you, there isn’t that much out there to draw from. Most poster books qualify more as coffee table décor than scholarly publications, and even then, the best written academic studies of the poster are rarely in English or have such a limited run that they’re impossible to find. There isn’t even a singular online authority where one can go to conduct proper research, as many of the best websites just flat out contradict one another.

Encyclopedic museums are no better. While most major institutions like the Chicago Institute of Art or the Metropolitan Museum of Art will have (European, mostly French) posters on display at one time or another, they are usually relinquished to a small side room near the Impressionists, showcasing a smattering of posters from their collection. And, without fail, those rooms are dull, confusing, and poorly curated. #SorryNotSorry

There needs to be a place where posters are treated with the respect they deserve not only as art but also as historic documents that can tell more about the day-to-day life of a citizen of that culture than most historic texts. Through posters, I’ve seen hysteria devises (read: vibrators) promoted as cheerful cure-alls, underwear invented by doctors, wine laced with cocaine as an afternoon pick-me-up, and green soap promising to make you lose weight. These delightful, strange tidbits of history rarely make the footnotes in textbooks – but now they’re going to take center stage.

As curator, I want to explore our shared history with posters – what they say about different cultures and times, both from a graphic design perspective and a sociological one. While European posters tend to be the most widely-studied and available, I also am committed to showcasing posters from as broad and diverse a background as possible – I want the posters of Ghana to have just as must gravitas as those of Toulouse-Lautrec, the zippy designs of 1960s Japan to be held up against the master of Modernity, Müller-Brockmann. And through all this, we will discover the small, the weird, the exciting aspects of culture and commerce that no other museum has ever explored.