A Brief History of PSA Posters

Last week, we hosted an amazing workshop with Isometric Studio during which our Chief Curator gave a wonderful history of the poster as Public Service Announcement. Below is an edited version of that lecture.

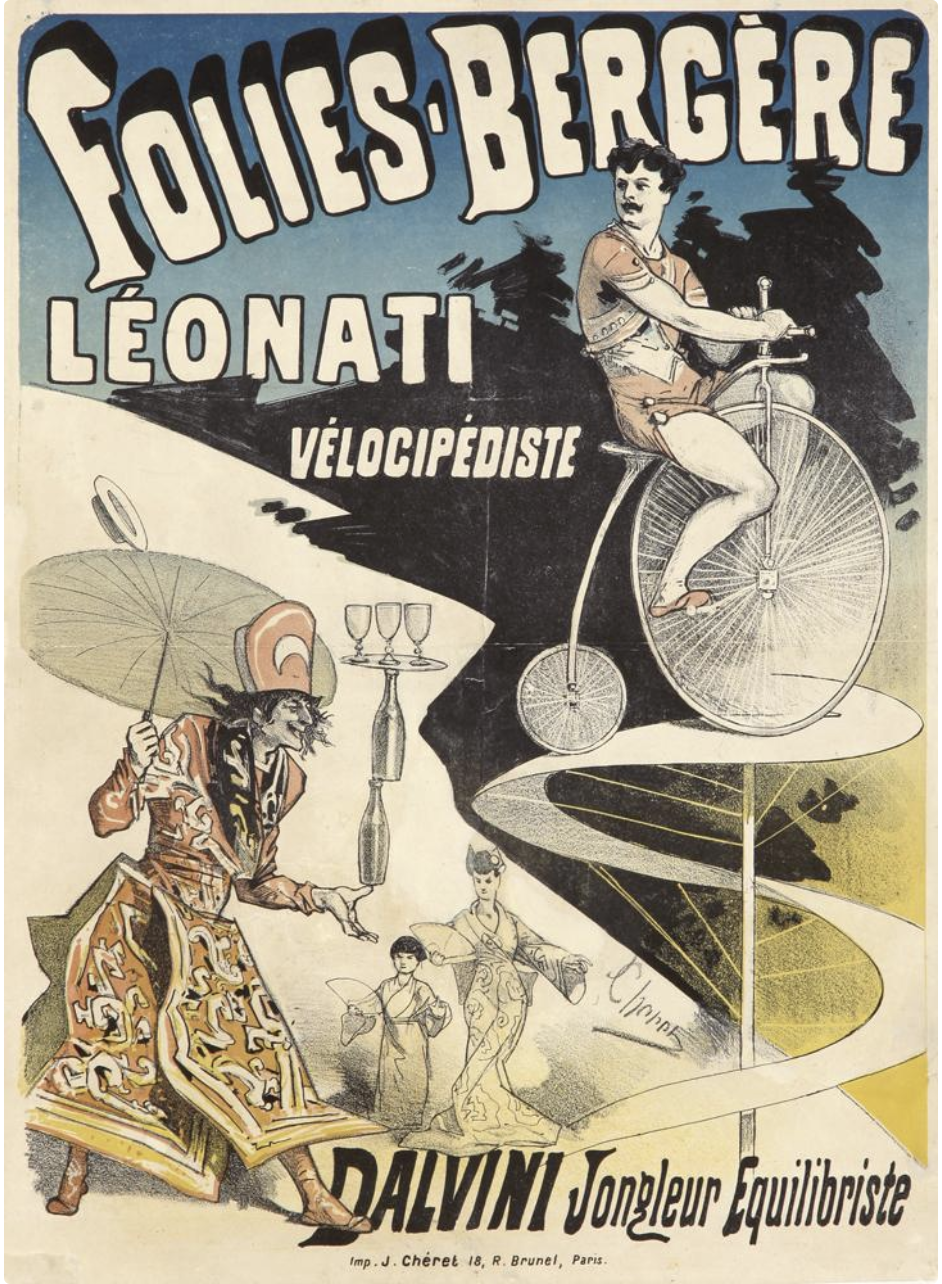

Folies-Bergère/Léonati, Jules Chéret, 1880

(image c/o Pinterest)

Posters as we think of them today first appeared in the late 1860s in Europe. They were large-format, color lithographs like the above image by the Father of the Poster, Jules Chéret, and they were generally used to advertise a variety of events or products, from cigarette rolling paper to hair tonic to biscuits. While advertising certainly existed prior to this period, it was either something you saw in a magazine or newspaper, or that you came in contact with as a broadside or a printed notice on the street. And in all of these cases, what you saw was typically text-based rather than image-based, meaning that in order to fully take in any of these ads you had to be literate. It also meant merely by the fact that you received the information through a periodical like a magazine, that you were an active participant in absorbing that information. So, you had to make the effort to gain access to that ad. Magazines don’t just hit you in the face; you have to go out, buy one, and turn the pages.

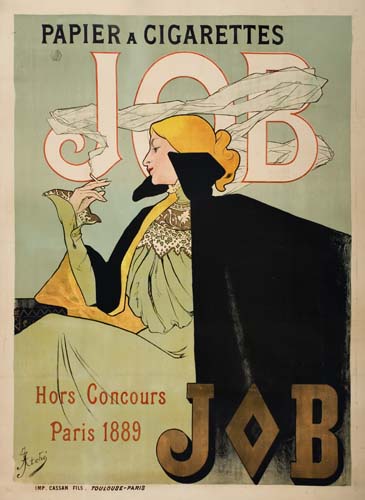

Left: Job, Jane Atché, 1889

(image c/o Swann Galleries)

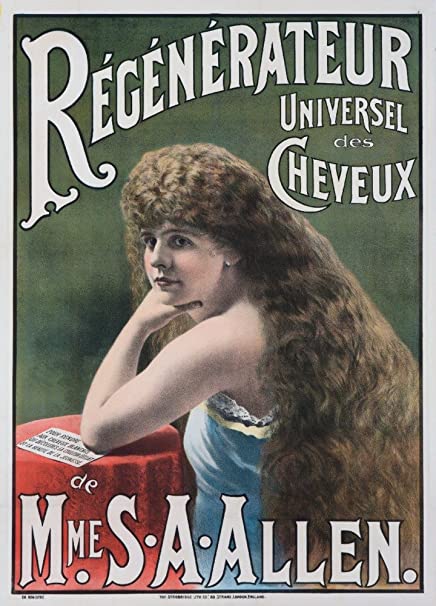

Right: Régénerateur, Designer Unknown, c. 1886

(image c/o Pinterest)

All of this changed with the advent of color posters. Now image rather than text was the dominant force. You don’t need to read that the poster above is for cigarette rolling papers—you can tell just by the presence of a woman smoking that this is probably an ad for something to do with cigarettes. The same goes for the poster on the right: such an abundance of hair would imply that one can obtain luxurious locks through whatever product is being promoted. As an advertiser, you now have access to everyone regardless of literacy, income level, interest—there is no barrier for entry. And the images are on the street, so they can’t really be ignored. If you go outside, you will come in contact with these ads whether you like it or not.

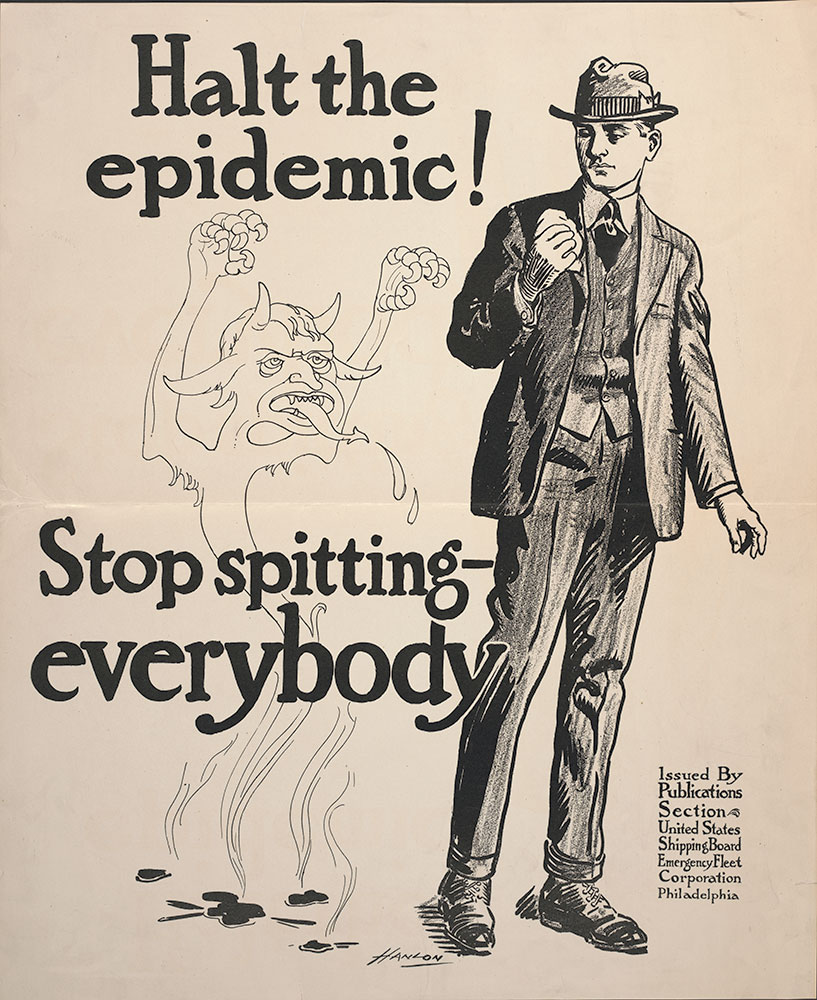

Left: Halt The Epidemic, Hanlon, c. 1918

(image c/o Reddit)

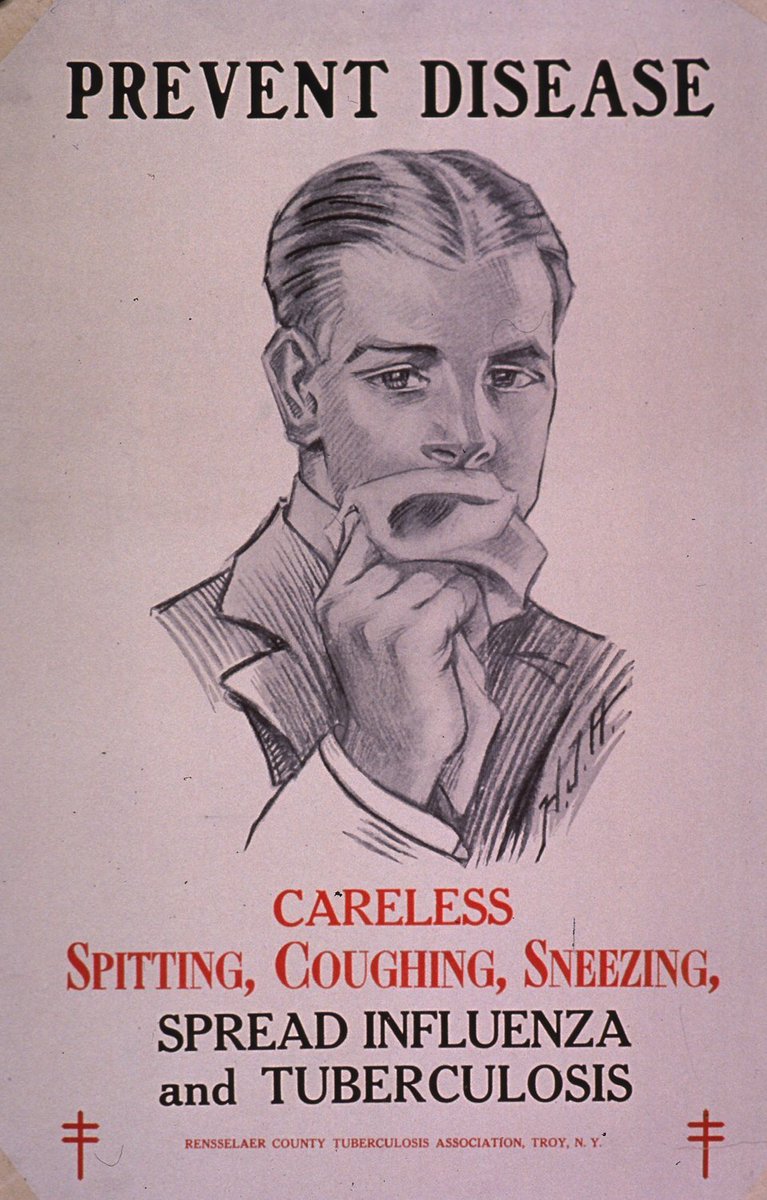

Right: Prevent Disease, HJH, c. 1918

(image c/o Twitter)

Interestingly, it took the government and other organizations interested in informing the public a while to tap into the functional use of posters. We don’t really see PSAs as we think of them today until around World War I. That’s almost 50 years since large-scale poster advertising first appeared. There are obvious exceptions to this rule, but by and large there isn’t a mass push to inform the public of necessary or helpful information until the mid-to-late 1910s.

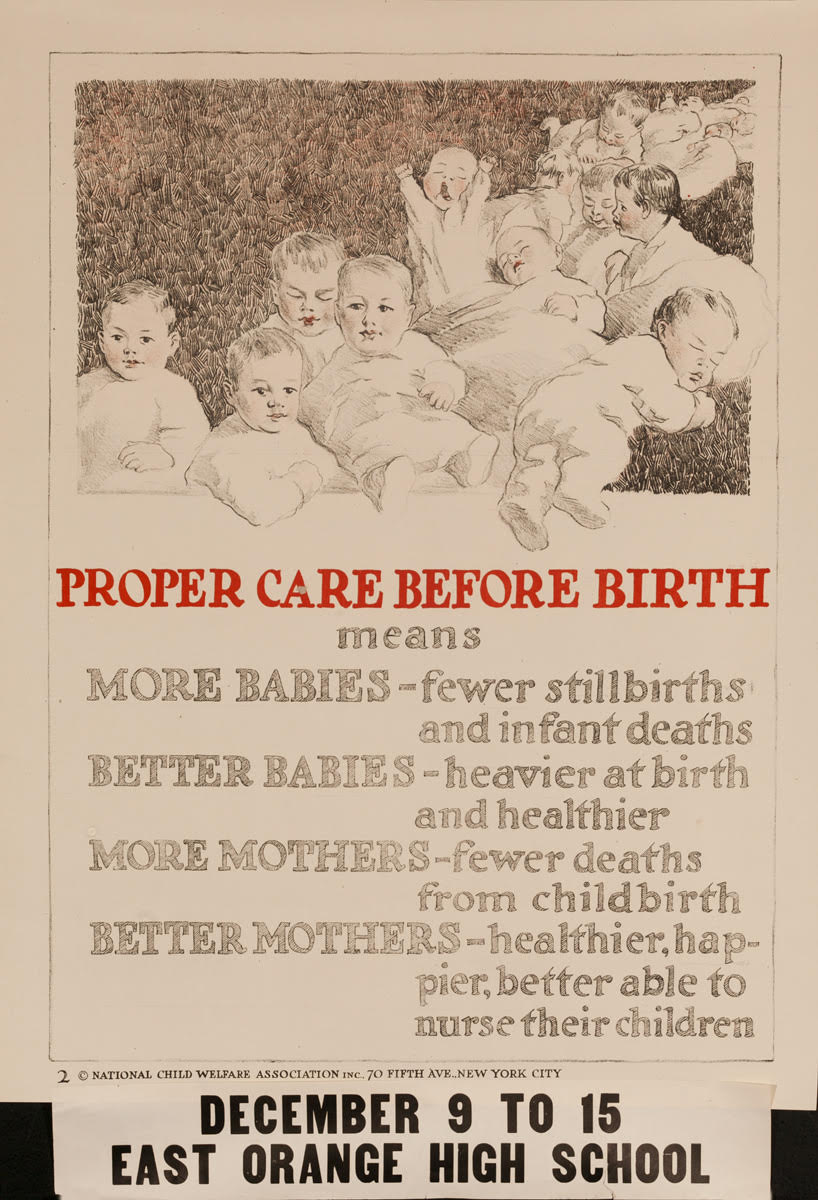

Left: Birth Registry, Designer Unknown, c. 1918

Right: Proper Care Before Birth, Designer Unknown, c. 1918

(images c/o David Pollack Vintage Posters)

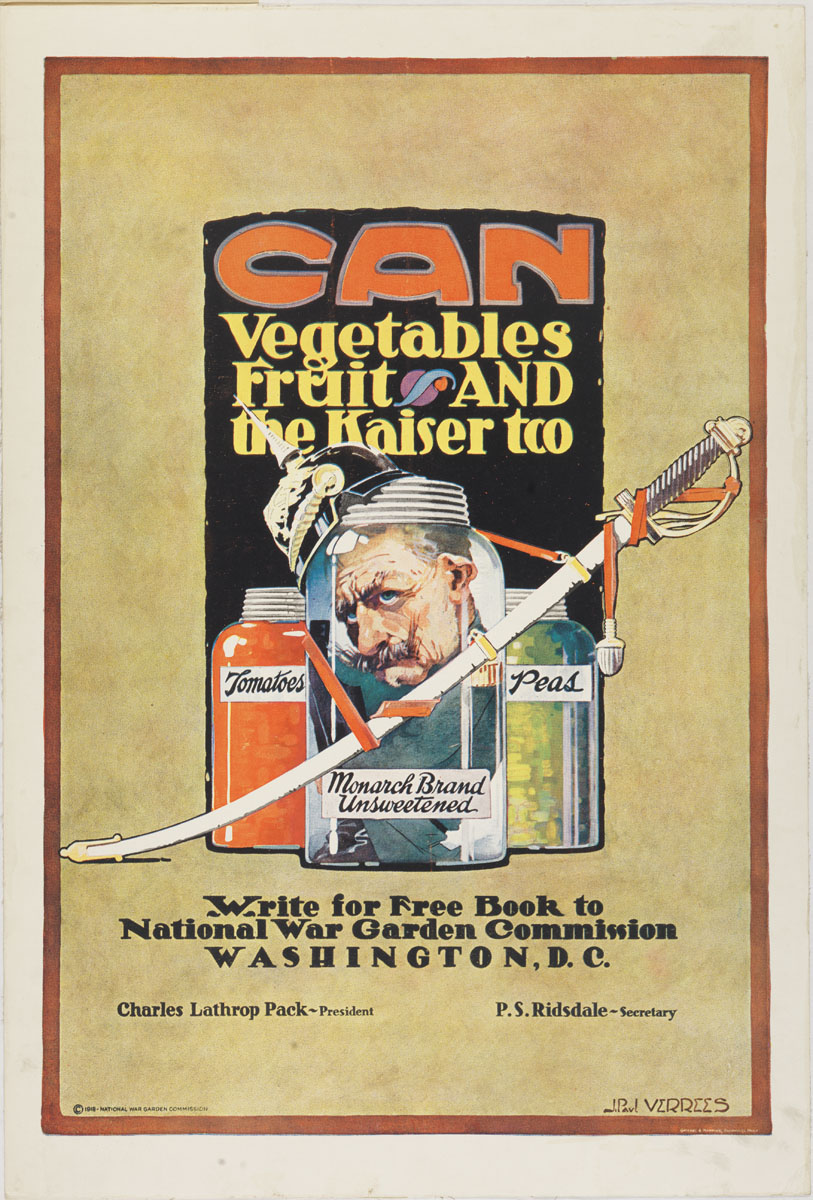

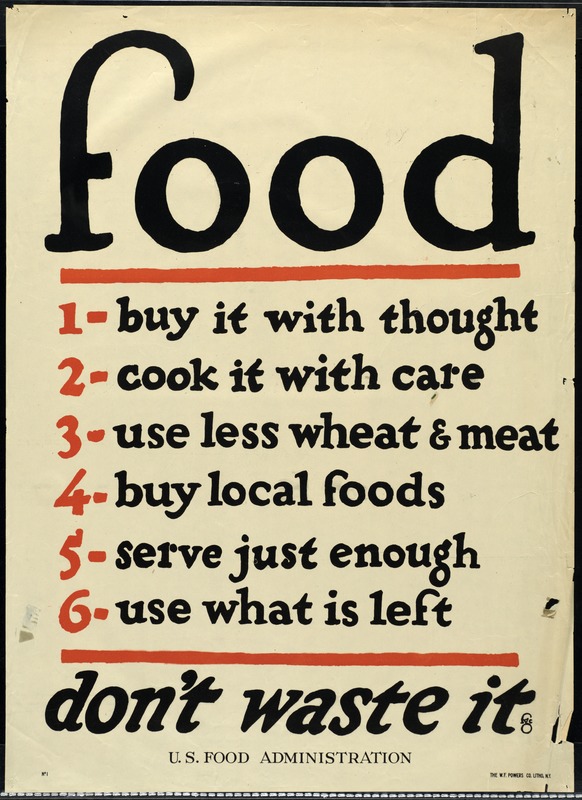

At this time, you start seeing a combination of posters aimed at informing people about public health issues, like the Spanish Flu, as well as posters instructing people to take advantage of public initiatives, like the birth registry, prenatal care options, and the push for a living wage as a means of ensuring a good environment for raising a child. This is also the time that you start seeing posters telling citizens how they can help the war effort through conservation of food. And you’ll notice that the motivating force in these images is a sense of civic duty or patriotism—that by following these guidelines you are proving yourself to be a good American.

Right: Can Vegetables, Fruit, and The Kaiser, J. Paul Verrees, c. 1918

(image c/o Wikimedia)

Left: Food, Don’t Waste It, Designer Unknown, 1917

(image c/o Digital Commonwealth)

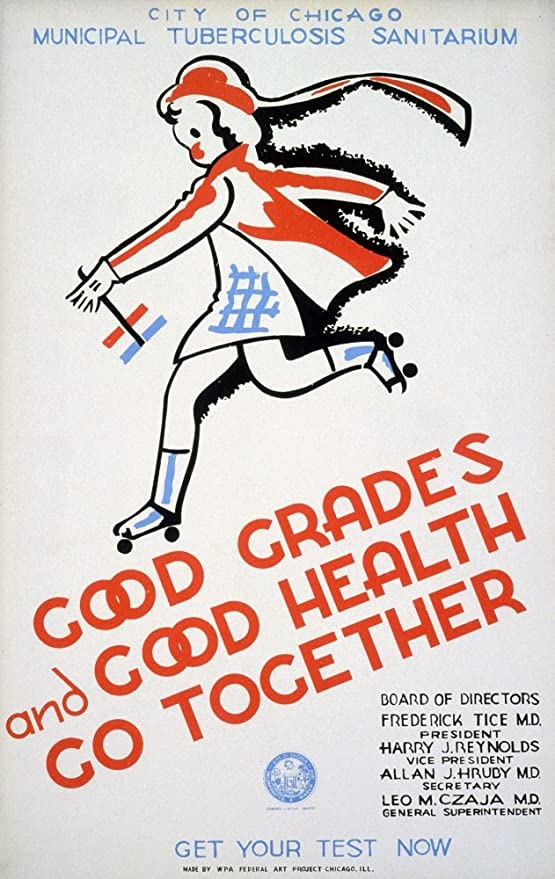

Then, in the 1930s, FDR’s WPA created thousands of posters around New Deal initiatives, many of which highlighted issues of public health and work safety. These were mostly created at a very local level, and were predominantly silkscreened rather than printed through lithography. This meant smaller runs, faster designs, and a lot of creativity.

Right: Good Grades and Good Health, Designer Unknown, c. 1939

(image c/o Amazon)

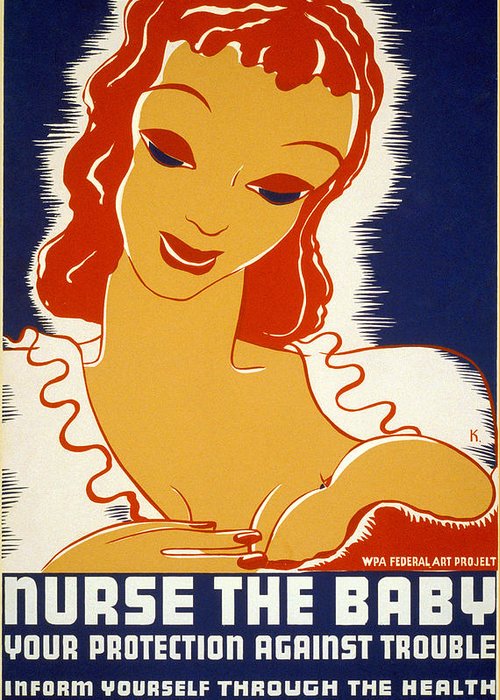

Left: Nurse the Baby, Designer Unknown, c. 1937

(image c/o Fine Art America)

Note how the image on the left indicates that it was created for the city of Chicago, while the image on the right could be used nationally.

Left: When You Ride Alone, Weimer Pursell, 1943

(image c/o Yale University)

Right: Save Your Cans, McClelland Barclay, 1943

(image c/o The University of Northern Texas)

By the time we entered World War II, poster PSA messaging shifted toward how you, as a non-enlisted citizen, could help the country and your community. So, posters about carpooling to save resources became commonplace (above, the image is saying that you’re helping Hitler win if you don’t rideshare), as did posters instructing women to save cans for ammunition or kitchen grease for explosives.

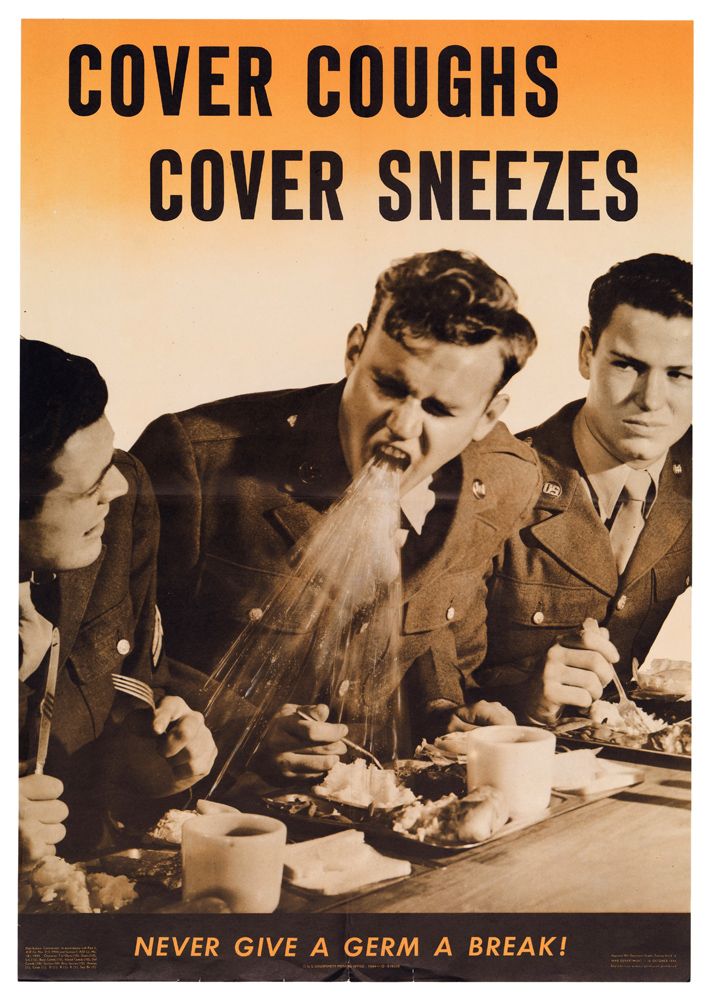

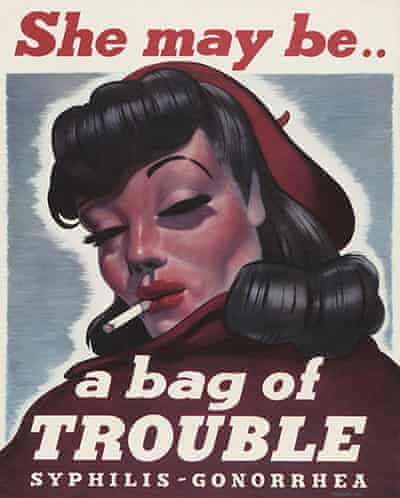

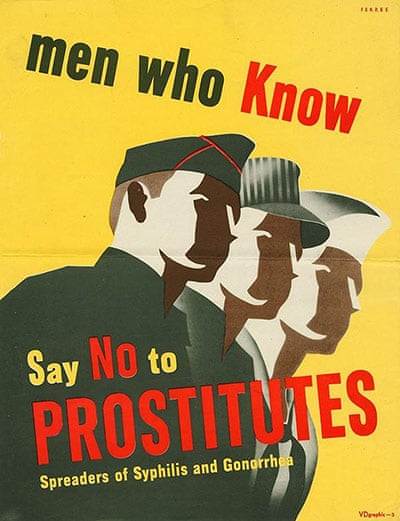

Left: A Bag of Trouble, Designer Unknown, c. 1940

Right: Men Who Know, Ferree, c. 1941

(images c/o The Guardian)

PSAs also found their way into army barracks, where we see a ton of images instructing soldiers on matters of sexual health. It’s often asked why there are so many STD posters from WWII, and the answer is pretty intuitive, but nonetheless shocking. At any given time during World War I, 15% of US troops were unable to fight because they were being treated for STDs, most of which they got while sleeping with good time girls abroad. In fact, Woodrow Wilson is credited with saying something along the lines of if we had come up with a way to cure VD, we could have gotten out of the war a year earlier. So, during World War II, we wanted to make sure that we weren’t losing troops to preventable diseases. Posters like the ones above were widespread within all branches of the military.

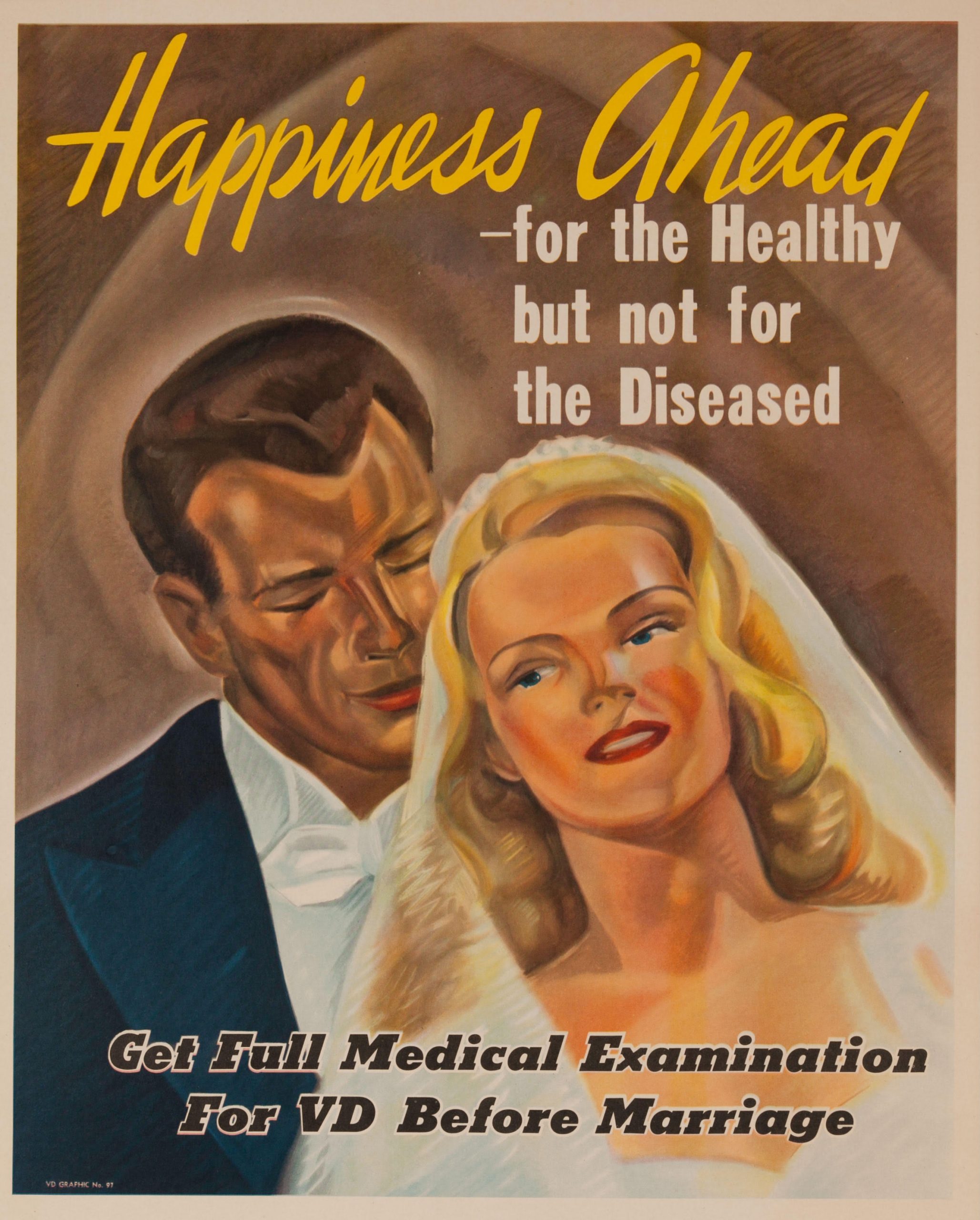

This concern continued even after the war ended, with posters like the one below instructing couples to get tested prior to marriage (just in case the guy brought something back with him from Europe).

Happiness Ahead, Designer Unknown, c. 1945

(image c/o Reprobate Press)

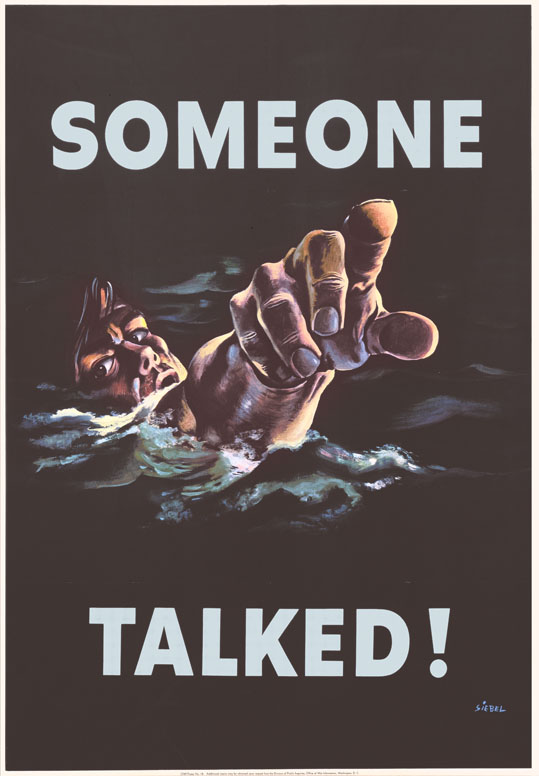

There was also a very effective campaign in Europe and the United States during WWII about being careful of what you say. If you wrote your wife that you were heading into battle on a specific date or in a specific location, that could be intercepted and result in your entire platoon being killed. If you said something in your local bar about what your friend in the army told you, someone spying for the enemy could hear it. Even the girl you pick up one night for a good time could be working for the other side.

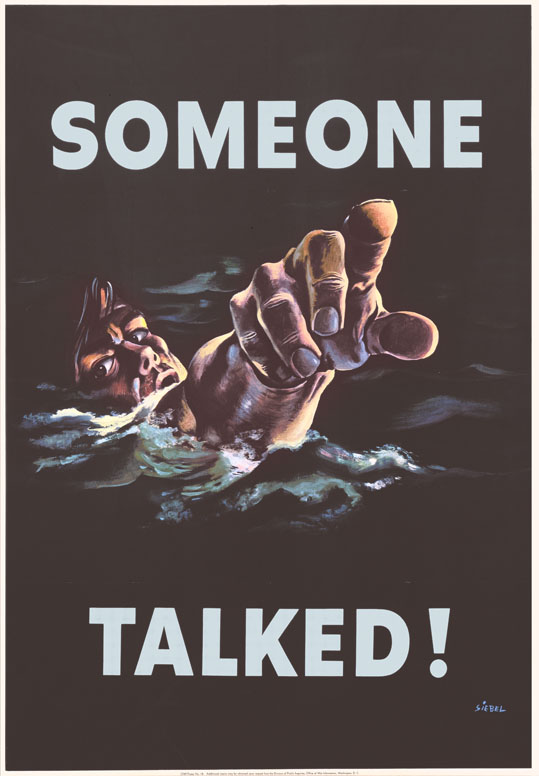

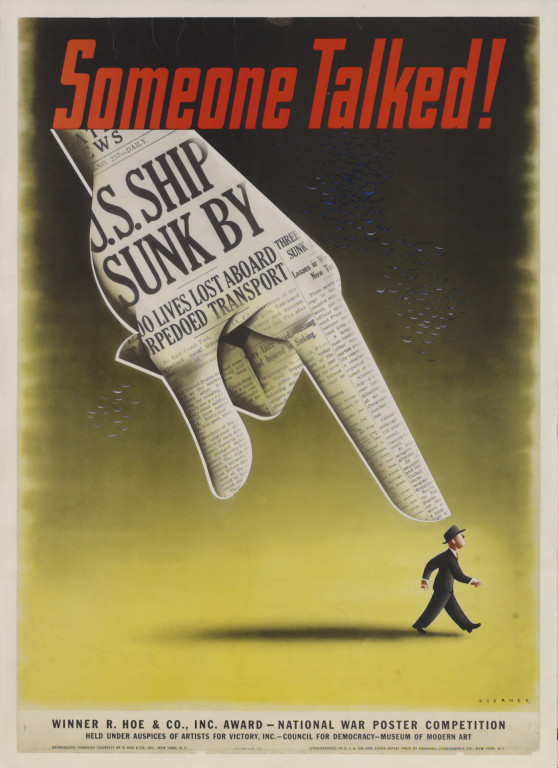

Right: Someone Talked, Frederick Sieble, 1942

(image c/o Poster House Permanent Collection)

Left: Someone Talked, Henry Koerner, 1943

(image c/o Swann Auction Galleries)

This concept of leaking information was a real threat since the element of surprise was essential to winning the war. As such, posters like the ones above indicating the dramatic consequence of leaked information became commonplace. On the left, you see a sailor drowning because his ship was torpedoed. He’s pointing toward the viewer, presumably the person who let his location be known to the enemy. On the right, a deadly headline—US Ship Sunk—points to the person who may have caused it. The point of all of these types of posters was to make both the accusation and the loss feel personal.

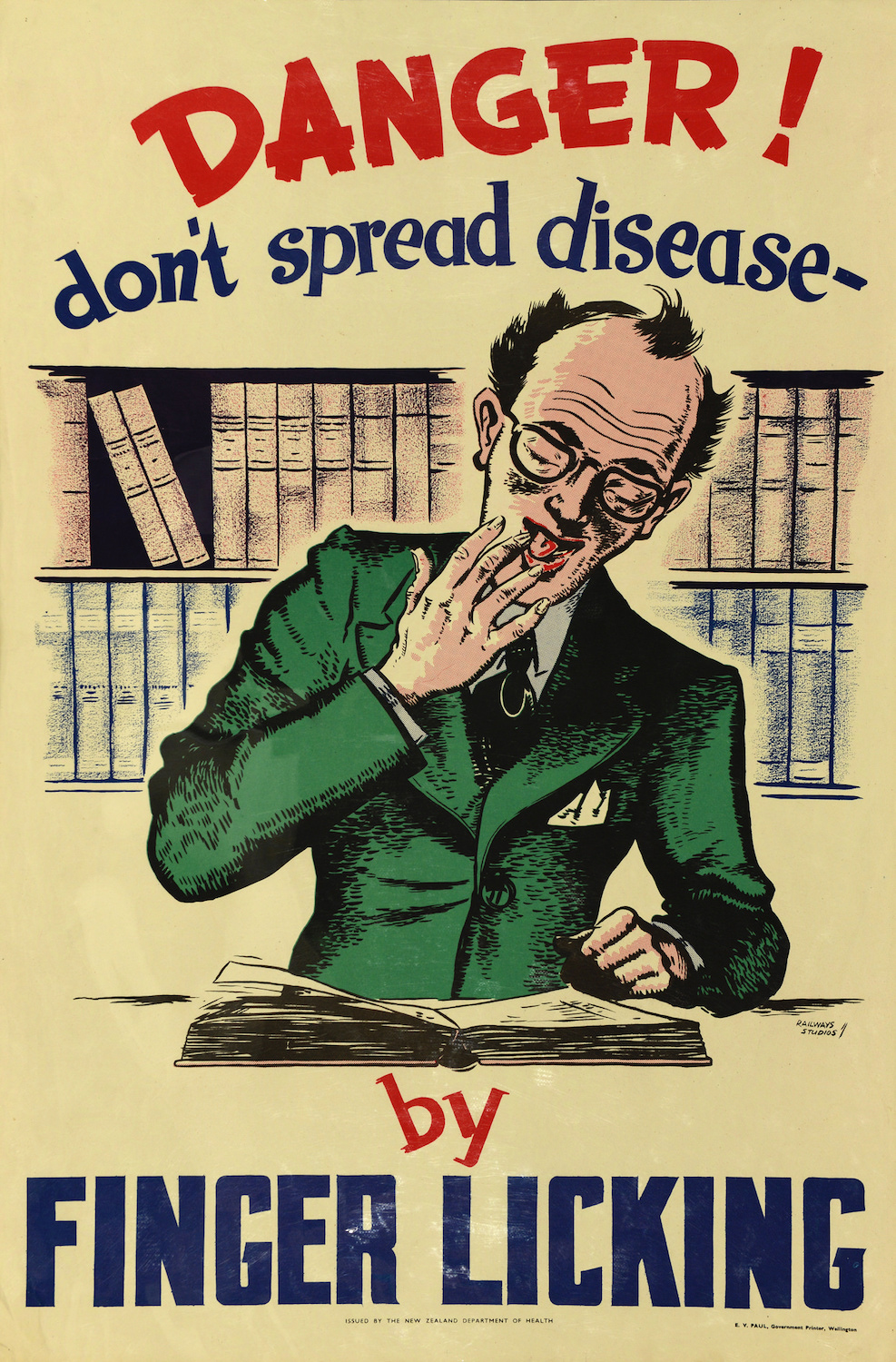

Left: Finger Licking, Railways Studios, c. 1955

(image c/o Ali Express)

Right: Wash Your Hands Before Eating, Designer Unknown, c. 1955

(image c/o Rare Historical Photos)

PSAs continued to be prevalent in most countries throughout the 1950s and 60s, especially as science started emphasizing the need for mass public health action. This is how we stopped tuberculosis, polio, and other major diseases that we don’t even think of today. And a major part of eradicating them was educating the public. That’s really what PSAs are—a means of informing and teaching the public en masse. It goes back to that idea I mentioned in the beginning of this post of not having to seek out information, but just being presented with it. Keeping the barrier for entry low means more people will see and absorb the information.

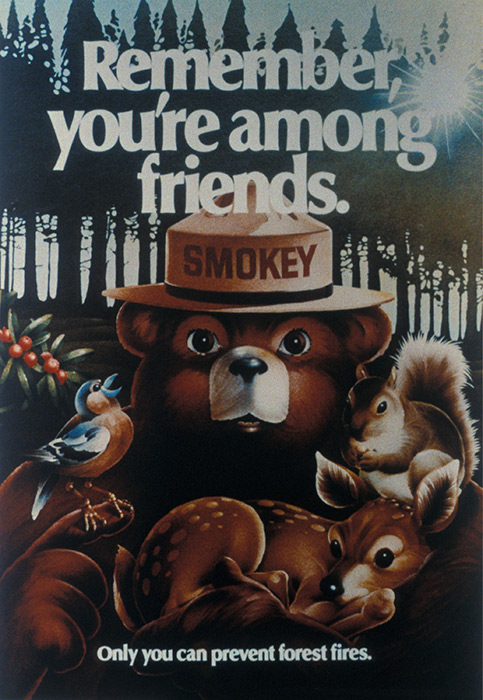

Left: Remember, Designer Unknown, 1987

(image c/o Smokeybear.com)

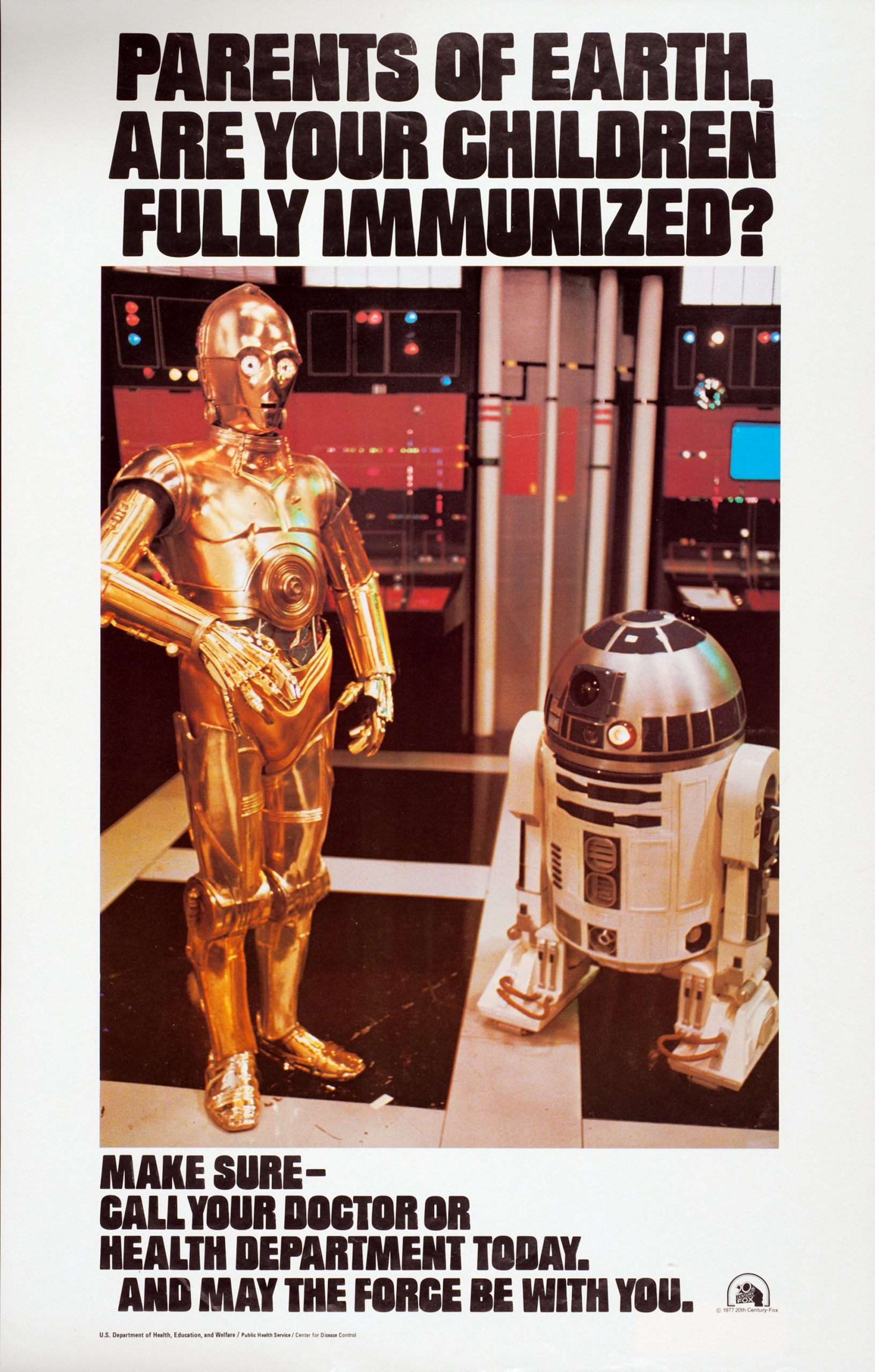

Right: Parents of Earth, Designer Unknown, c. 1977

(image c/o US National Library of Medicine)

By the time we hit the 1970s & 80s, PSA posters are everywhere and covering a variety of social concerns, from everybody’s favorite bear telling you how to prevent forest fires to Star Wars characters reminding you to vaccinate your children. This is also the moment when the idea of celebrity or pop culture entering into the PSA space really takes hold. Remember when at the end of GI Joe cartoons you’d see a “knowing is half the battle” clip or when there’d be a “very special” episode of a popular teenage show, typically discussing issues of domestic violence, teen pregnancy, or drug use? Using familiar, beloved characters to get a message across proved very, very effective and started to dominate the PSA genre.

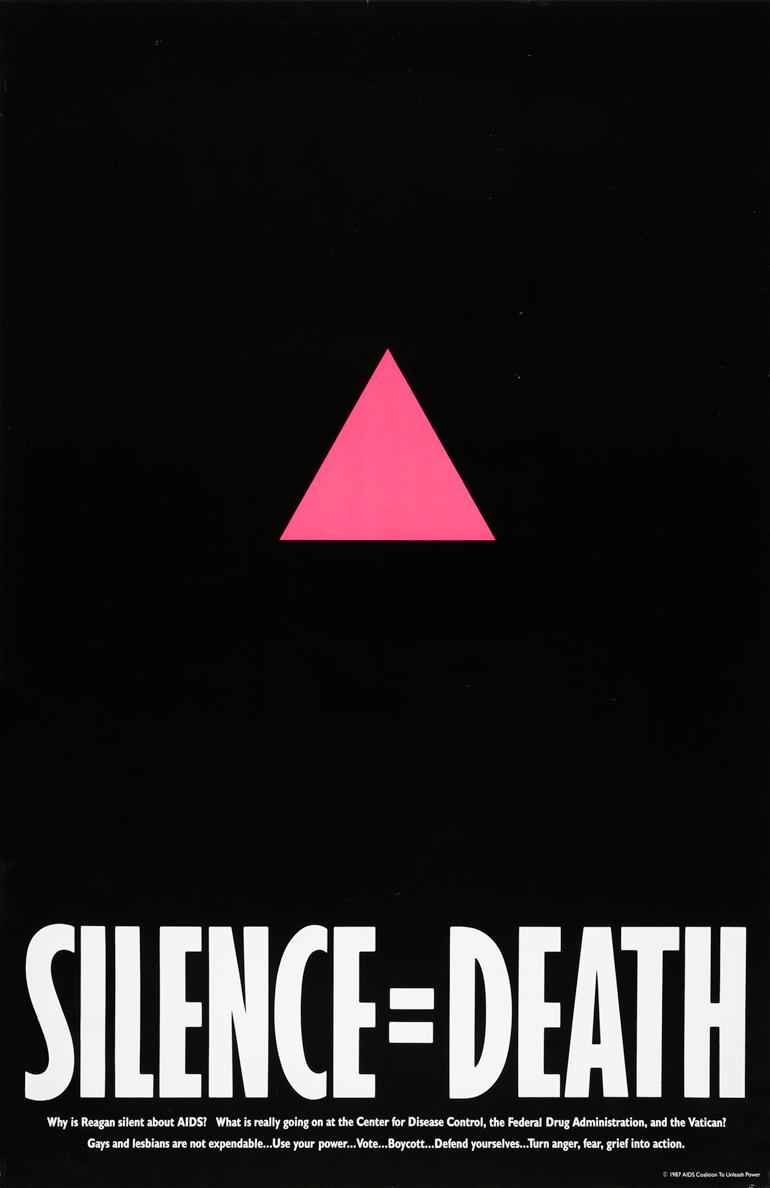

Silence=Death, Avram Finkelstein, 1987

(image c/o Poster House Permanent Collection)

This is also the era when iconic posters like ACT UP’s Silence=Death image became symbolic as both a protest poster and a means of getting people to recognize the severity of the AIDS crisis.

Now, this is just a small snapshot of the history of PSA posters in the United States, with a few images from Europe. But PSAs exist in all countries, as the need to disseminate information about public health and safety quickly and efficiently is universal. While not anywhere near exhaustive, I’m going to share a few images to indicate the diversity within the genre from around the world—all of which are worthy of their own targeted research.

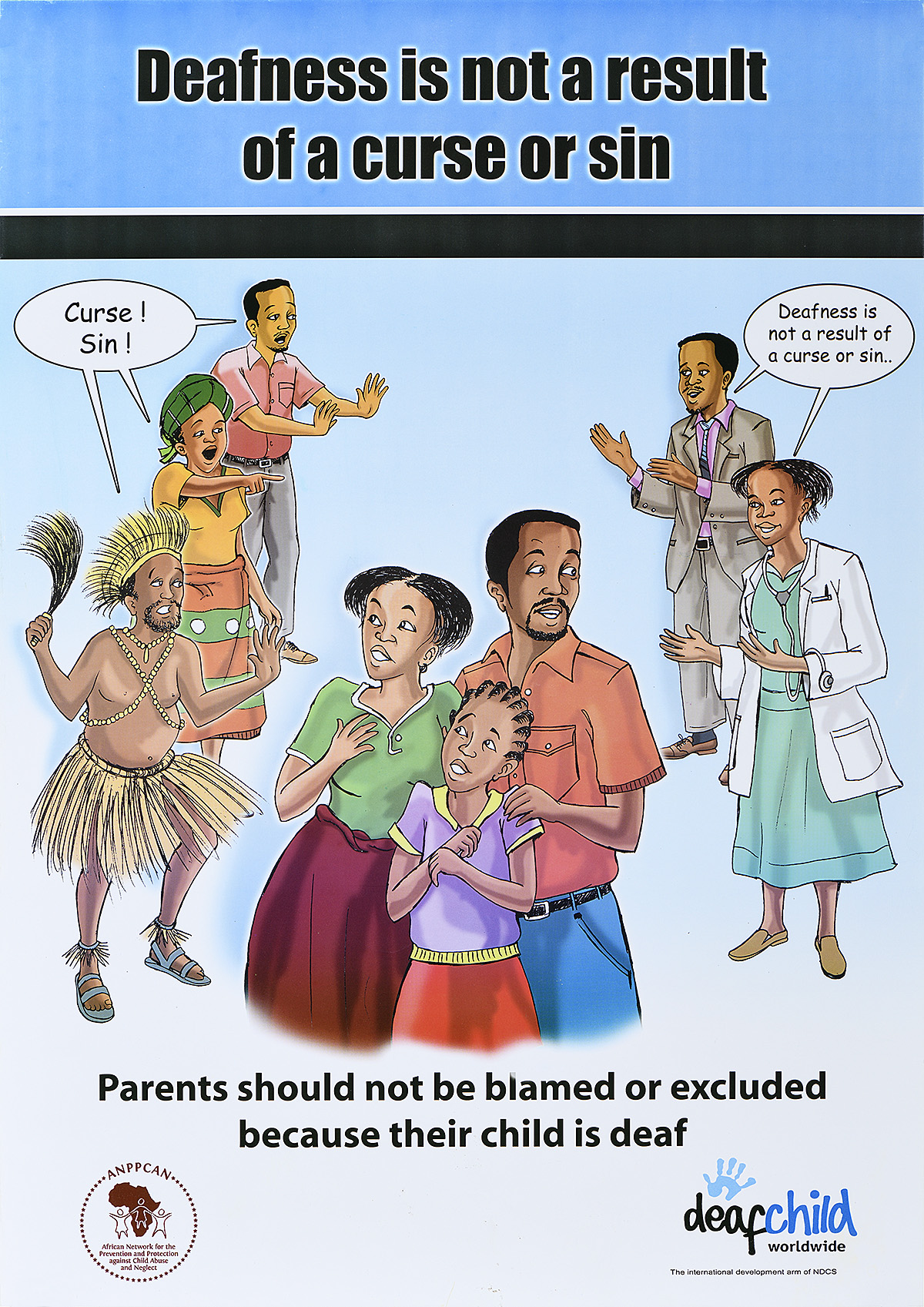

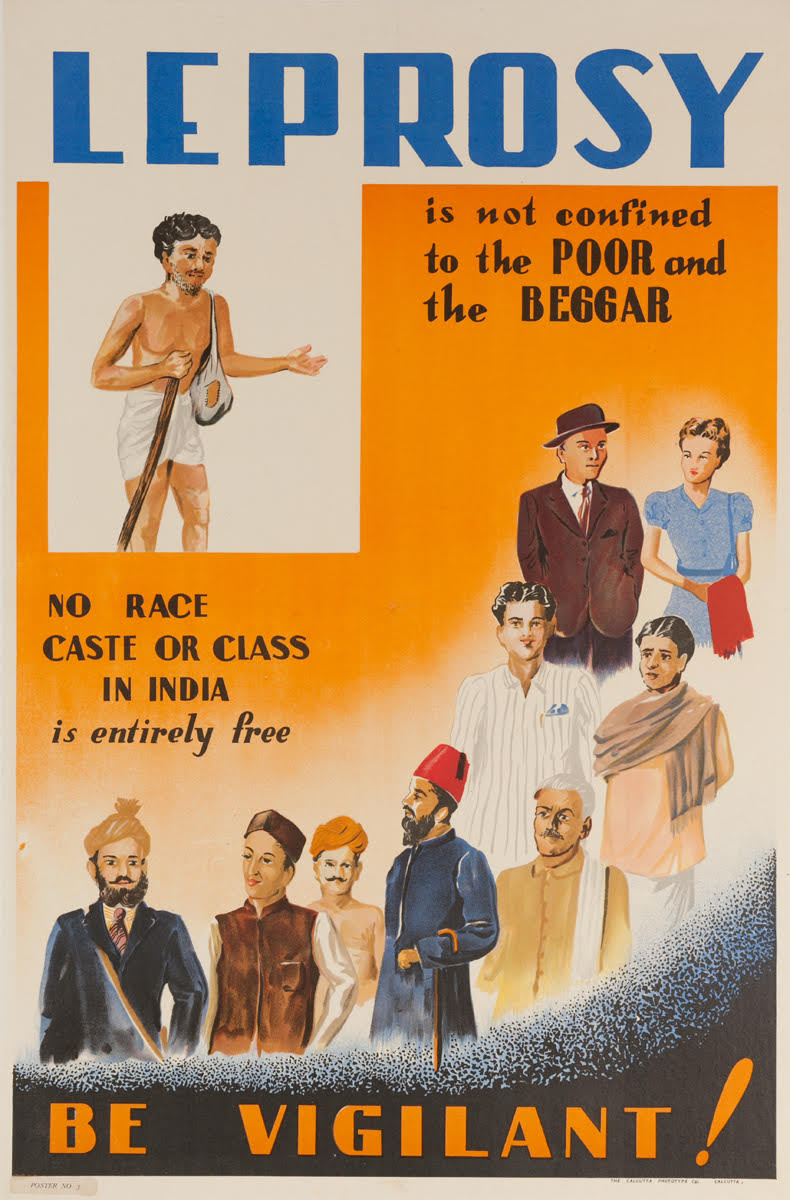

Below is a poster from Kenya talking about informing citizens that disabilities—here specifically deafness—are not the result of a curse being placed on a family, and that the family of a child with a disability should not be shunned by society. The second poster highlights the fact that diseases like leprosy do not discriminate based on class or race, and that anyone can contract them.

Left: Deafness, Designer Unknown, c. 1999

(image c/o Poster House Permanent Collection)

Right: Leprosy, Designer Unknown, c. 1955

(image c/o David Pollack Vintage Posters)

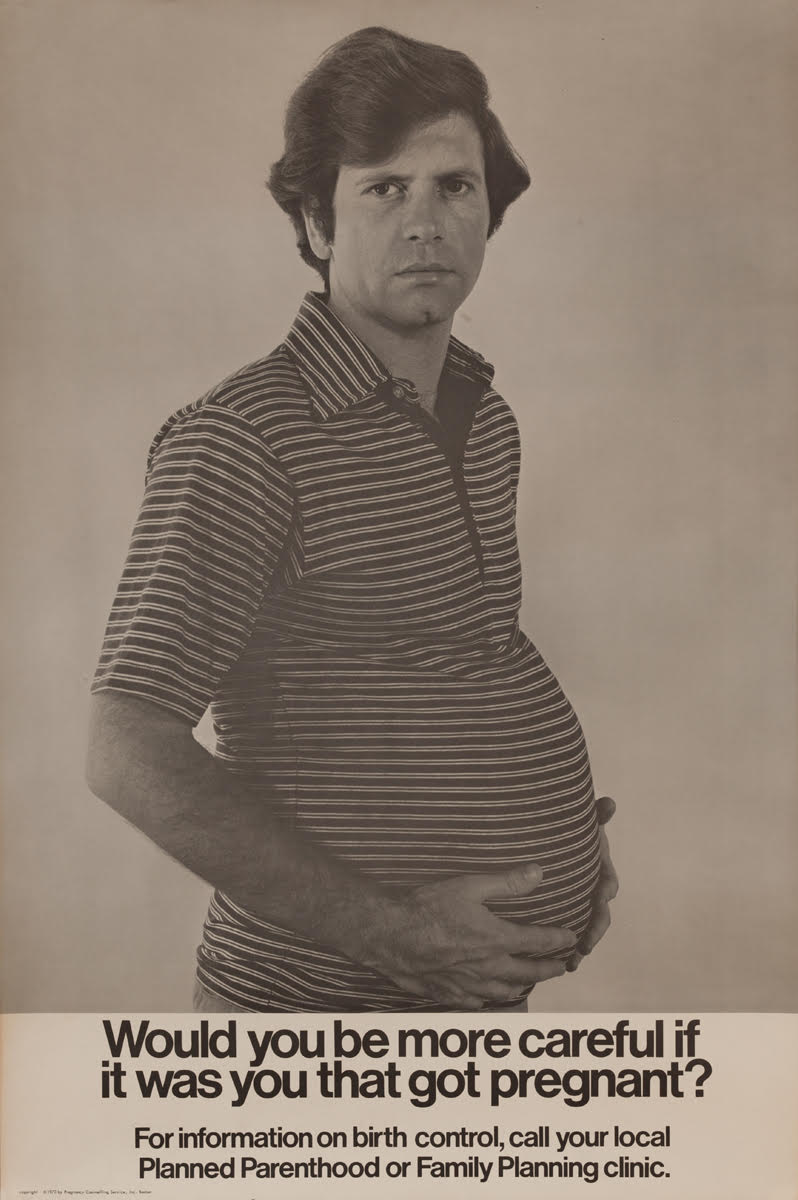

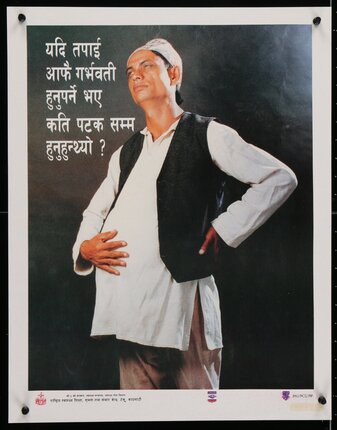

The next two posters (from the USA and Nepal respectively) are actually riffing on an iconic image that Saatchi & Saatchi created in 1970 about birth control and reproductive rights. They demonstrate the pervasive power of a good advertising concept being able to reach any audience, anywhere, regardless of culture or country.

Right: Planned Parenthood, Designer Unknown, c. 1973

(image c/o David Pollack Vintage Posters)

Left: If You Had to Be Pregnant, Designer Unknown, c. 1995

(image c/o Chisholm Larsson Gallery)

Now that we’ve touched on the general history of PSA posters, I want to bring us into how they’re being used today. So many groups are creating PSAs, particularly for digital spaces like Instagram and Facebook, in response to the Covid-19 outbreak.

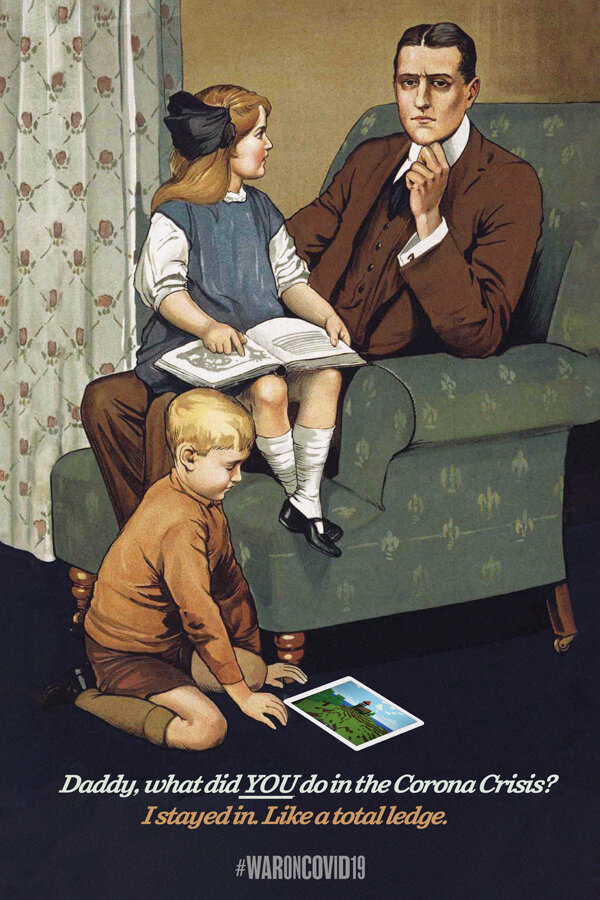

The Amplifier Foundation (perhaps best known for its affiliation with street artist Shepard Fairey) has issued an open call to artists to submit poster designs. Many of the submitted images actually reference historic posters from WWI and WWII. The same goes for the #WarOnCovid19 campaign in England, whose designs very clearly take classic poster imagery and update them for the current crisis. In this latter campaign, the posters are not just for digital use, but are also being printed and pasted around London.

Left: We Can Do It, Pegah Kavousi, 2020

(image c/o The Amplifier Foundation)

Right: Daddy, What Did You Do, #WarOnCovid19, 2020

(image c/o #WarOnCovid19)

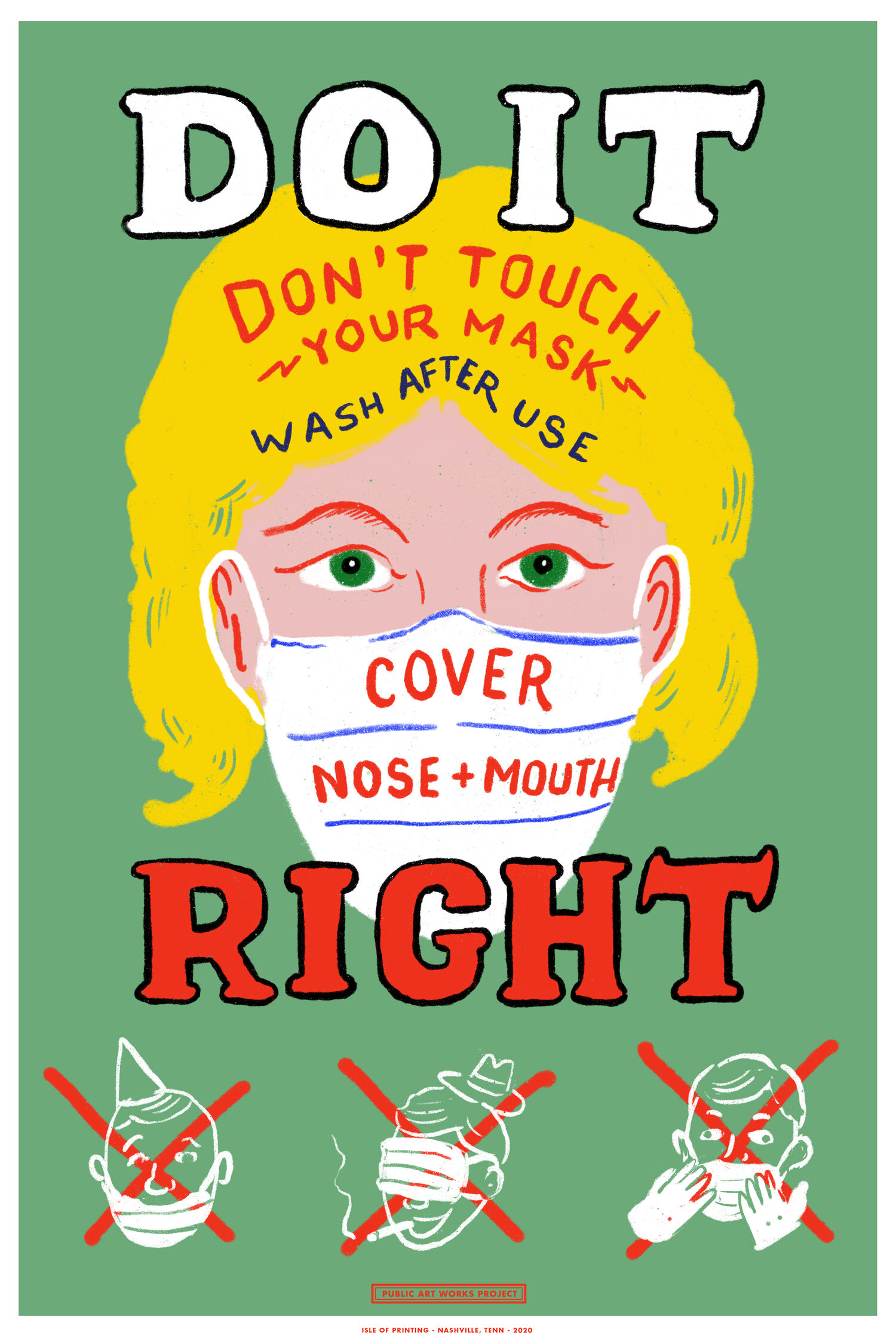

Then there are places like Isle of Printing, a letterpress studio in Nashville, that are creating unique posters to inform the public. But whether based on pre-existing images or not, tons of very different parts of the design world are currently coming together for a common cause—and that says a lot about the power and appeal of the poster as a medium.

Do It Right, Isle of Printing, 2020

(image c/o Isle of Printing)

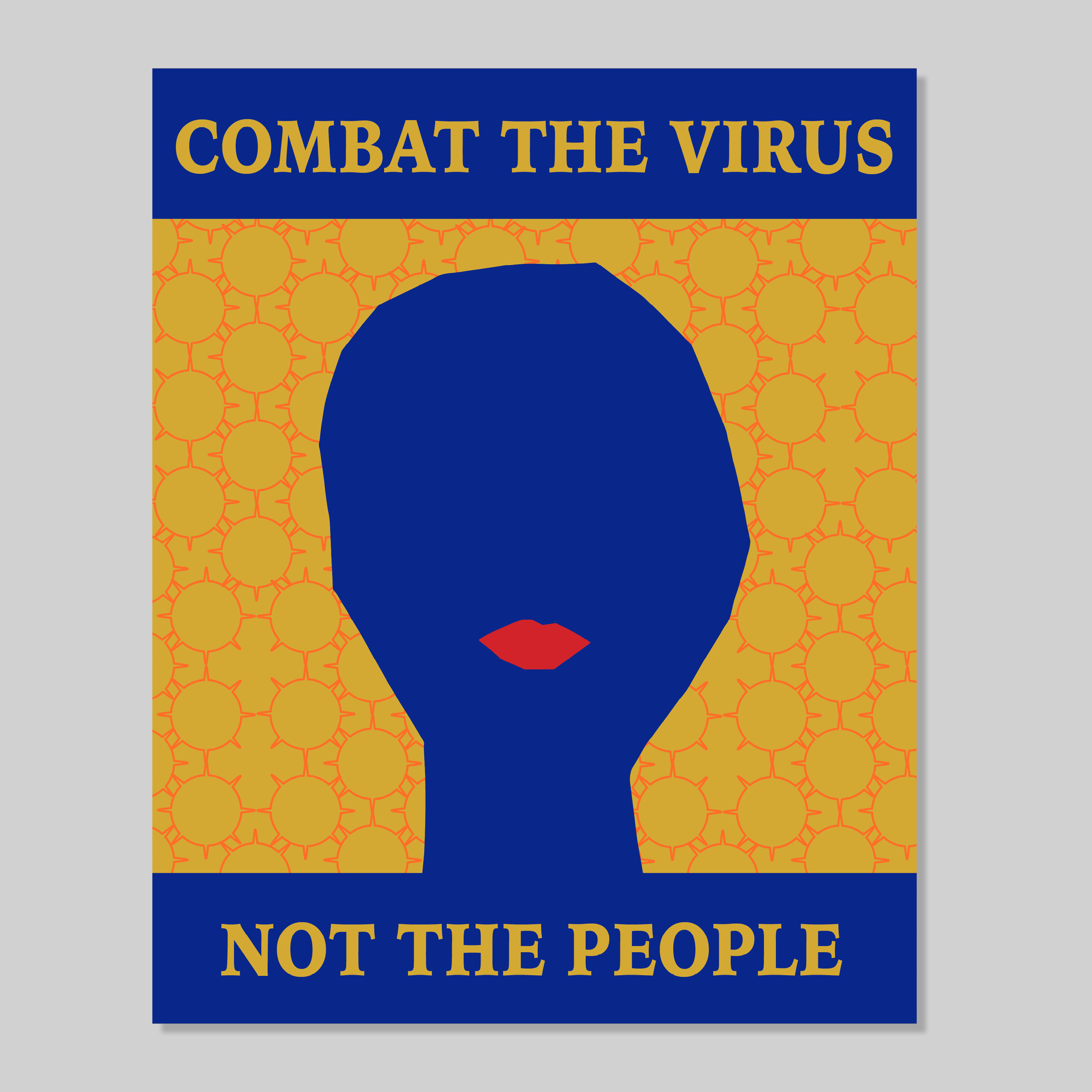

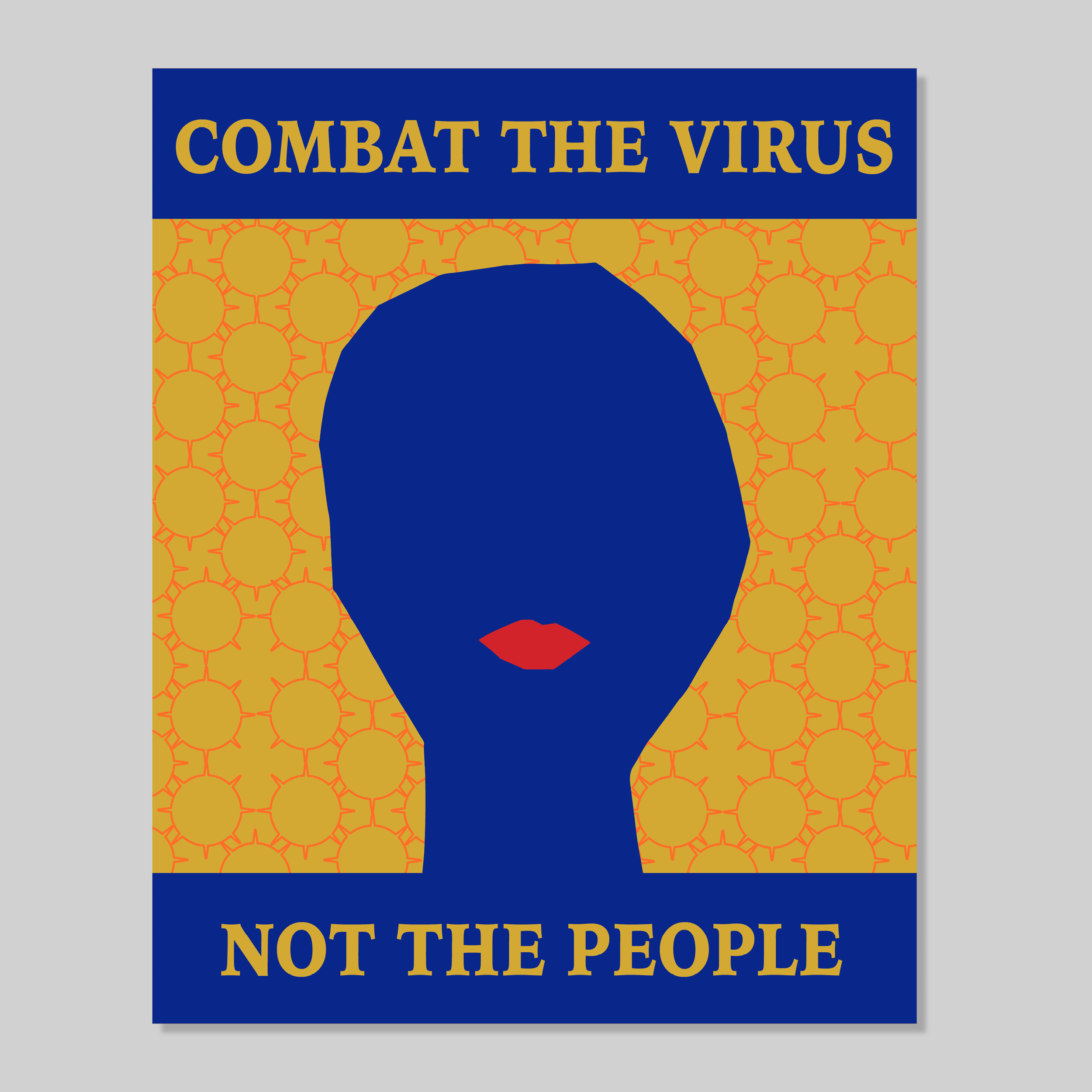

We at Poster House asked designer Rachel Gingrich to create a set of digital PSAs for us when we heard about the shocking and incredibly disturbing treatment of Asian Americans as a result of the misconception that they are responsible for Covid-19. This led to our in-house designer Mihoshi Fukushima Clark creating her own PSAs. Both of sets of digital posters are available for download on our website and were made specifically for use on the internet.

Left: Combat the Virus, Rachel Gingrich, 2020

Right: Quarantine Bigotry, Mihoshi Fukushima Clark, 2020

As technology continues to unite the world in the digital space at unprecedented speed, PSAs will evolve to be both very broad and universal as well as extremely targeted and niche. Designers are responding to public health concerns on a mass scale, and information (as well as misinformation) can be spread in seconds. The PSA isn’t going anywhere, but the ways in which we encounter them will be different—some will be posters, but others may gifs, commercials, push notifications, or formats we’ve never even considered.

If you see a PSA poster in the wild, please share it with us on social media!